Sandro D’Amico, ND

Consider the following

patient:

- 16-year-old boy

- Born to a drug-addicted mother

- Severe physical abuse and neglect as an infant and toddler, resulting in removal from his home by Child Protective Services and placement in foster care

- Adoption into a stable family at 2.5 years

- Throws and breaks things

- Increasingly angry and defiant towards parents

- Regularly violates limits set by parents

- History of fights at school

- Has punched both of his parents on multiple occasions

- History of cutting

- Moderate to severe depression

- Has recently been using alcohol and recreational drugs

Would you take this case? If so, what would you do for him? If you referred him, whom would you refer him to, and to what degree do you think they would be able to help him? If he doesn’t get the help he needs, what do you think the future holds for him?

Who we will be as mature human beings occurs through the profound interaction of our innate resources (genetics) with the environment (gestation, nutrition, experience, microbiome, xenobiotics). Under “good enough” conditions, the interaction of innate resources and environment fosters the development of a neurophysiology that is resilient and able to creatively negotiate the challenges of life.

Children and adolescents who exhibit inappropriate aggressive or violent behaviors represent individuals whose neurophysiology is highly stressed. These can be very challenging cases to deal with, and certainly not every clinician will feel equipped or inclined to take them on. However, given the prevalence of violence among youth,1 the lack of effective conventional options in many cases, and the potential consequences to an entire life of not receiving effective care when it is needed, it is important to recognize that naturopathic medicine has a lot to offer these patients.

Naturopathic medicine does not represent a standalone solution; however, a naturopathic doctor can contribute a unique and sorely needed perspective as part of a team that includes caregivers, supportive family members and peers, mental health professionals and community resources (such as programs for at-risk youth and youth crisis centers). Few conventional mental health professionals will consider, for instance, that violence or aggressive behavior can be influenced by nutritional, hormonal, genetic, epigenetic, pharmacologic, or xenobiotic factors. Nor are they trained to assess or address these factors. Furthermore, pharmacological approaches to treating neurochemical imbalances are limited in both conception and effectiveness,2 and carry potentially dangerous side effects.3,4 In contrast, many naturopathic doctors have a broad and nuanced understanding of neurochemistry and how to both assess and balance it.

Initial Intake & Assessment

In some ways, treating at-risk youth is no different from treating any other patient; however, it does require some special considerations. To begin with, oppositional or aggressive behaviors occur in the context of the child’s family and other social relationships. Parent-child stressors may be among the principle causes of the child’s behavior, or parents may represent a nurturing resource for the child. It is valuable, if possible, to meet and interact with both parents and to observe the parents interacting with each other and the child. In addition, a number of other psychological and circumstantial factors should be evaluated:

Do you have concern for the immediate safety of the child or other family members? What kind of support resources are in place for the child? Are they adequate? Has the child been abused psychologically, sexually, or physically? Is violence occurring between other members of the family? Is the child being teased or bullied by peers? Does the child have a history of a head injury? Is the child taking prescription or recreational drugs?

Parents and children are not always completely forthcoming, so it is important to pay attention to non-verbal cues, to dynamics between the parents and child, and between all family members and you. It’s also important to pay attention to your clinical instinct. If something “doesn’t seem right,” find a way to follow up on it that doesn’t jeopardize the trust you are trying to establish with the patient and their family.

This is Your Brain On Violence

Aggression can be predatory, ie, a calculated action to achieve a desired goal. However, in humans, and particularly in children, it is far more often defensive, ie, a biological response to a perceived threat. Neurologically, incoming sensory information is routed through the thalamus to both the neocortex and to a complex network of deep brain structures including the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, nucleus basalis, and locus ceruleus that are involved with assessment and response to potential threat.5 The perception of threat, which can be highly influenced by cortical and subcortical associations with prior experience, leads to widespread activation of both the cerebral cortex and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.6 A physiological response often precedes conscious recognition of the perceived threat.7

The neocortex, and particularly the orbitofrontal cortex, not only receives and responds to neural activation from these deep structures, but also has the critical function of modulating their activity.7 As with many things in physiology, this is a system of applying the gas and the brakes at the same time. Any factors which increase the reactivity of these deep structures (history of extreme stress or trauma, elevated testosterone, hypoglycemia, etc) or which weaken the activity of the neocortex (activation of traumatic memory, sleep deprivation, hypoglycemia, neurotransmitter imbalance, etc) increase the likelihood of defensive aggression and violence.5 Conversely, therapies which reestablish balance between cortical and subcortical activity restore executive control and decrease the likelihood of aggression and violence.

Diet

Dietary influences can be central or peripheral, but they are almost always present. It is important to take a thorough diet/symptom history and look for specific foods or classes of foods that trigger aggressive behaviors in the patient. Doris Rapp did pioneering work on this, and a number of dramatic case studies are recorded in her book Is This Your Child?8 Trigger compounds that are present in a number of different foods include added sugars, phenols, salicylates, food additives, and caffeine.9 While food allergy and sensitivity testing can be valuable in many clinical situations, for assessing diet-behavior associations, careful history-taking, diet/symptom logs, and trial eliminations are probably far more productive.

Assessing hypoglycemia is also important.10 Hypoglycemic episodes can trigger fight-or-flight neurochemistry while simultaneously downregulating cortical executive functioning, leading to disinhibition of aggressive impulses. Ask parents when episodes tend to occur in relationship to the patient’s last meal and after what specific types of foods.

Hormones

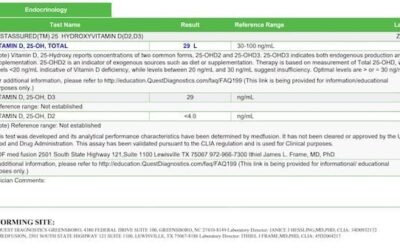

Both higher testosterone and DHEA-sulfate levels have been linked to aggression.11 In addition, there appears to be some correlation between violence and abnormal thyroid hormone levels,12 both high and low cortisol levels,11 and both estrogen and oxytocin receptor polymorphisms.13,14 For these reasons, it is a good idea to assess all major hormone systems through patient history and lab tests if indicated.

Low cortisol levels are common in children and teens, and should be considered as part of the complex of contributing factors when present. With aggressive patients, it is best to avoid the use of stimulating therapies, such as adrenal glandulars, as they may increase norepinephrine and epinephrine release from the adrenal medulla. Interestingly, while it is generally thought that ACTH only stimulates adrenocortical hormones, there is one small human study in which exogenous ACTH increased levels of adrenal norepinephrine and epinephrine as well.15 This suggests the possibility that in patients with low cortisol, ACTH stimulation of norepinephrine and epinephrine may continue without negative feedback. This could potentially explain the observation that patients with low cortisol are often quite anxious and emotionally volatile.

Neurochemistry & Nutrition

Serotonin plays a key role in the modulatory function of the neocortex, and numerous animal and human studies have found an association between decreased serotonin and violence.16 Indeed, serotonin is involved in orbitofrontal cortex regulation of the amygdala.17

There are many factors that can decrease serotonin activity in the central nervous system (CNS). Functional deficiencies of nutrients involved in serotonin synthesis, such as tryptophan, or the cofactors niacin, pyridoxine, vitamin C, iron, and zinc, are common and represent a powerful therapeutic option for affecting mood and neurochemical balance in a relatively short time-frame.

Abnormal cholesterol levels have been implicated in a number of mental health conditions.18 As a critical component of cell membranes and myelin, cholesterol has a powerful influence on neurological function. Cholesterol deficiency is associated with decreased binding of both serotonin and oxytocin to their receptors.19,20 A number of studies have found an association between low levels of serum cholesterol and violent behavior. One study of 4852 children, aged 6-16 years, found that non-African-Americans with a serum total cholesterol level below 145 mg/dL had 3 times the rate of suspensions and expulsions from school as those with total cholesterol levels above 145mg/dL.21

Omega-3 fatty acids – docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), in particular – are important components of neuronal cell membranes. Some studies have also shown a correlation between low levels of these nutrients and aggressive and violent behavior.22,23 While the mechanisms have not yet been clarified, it is likely that the influence of omega-3 fats on cell membrane fluidity plays a role.

Methylation of DNA and histone tails is the primary epigenetic process through which gene expression is downregulated. Hypomethylation of genes encoding for serotonin reuptake transporters can lead to their overexpression and, ultimately, a decrease in the availability of synaptic serotonin.24 Methylation profile testing can be used for assessment, and I have found S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) – the body’s primary methyl donor – to be very effective in modulating mood in hypomethylated patients.

In addition, abnormalities in serum copper, and the ratio of zinc to copper, have been found in a number of mental health conditions, including oppositional defiant disorder.25-27 Copper is a cofactor in the conversion of dopamine to norepinephrine, which is involved in the activation of the fight-or-flight response by the locus ceruleus. High levels of copper can be directly neurotoxic as well, as is seen in Wilson’s disease. Supplementing zinc improves the zinc-to-copper ratio and induces metallothionein, which binds copper intracellularly.28

Prescription Medications

Conventional healthcare practitioners do not often consider medications as potential causes of aggressive behavior. However, many medications commonly prescribed to pediatric patients do have the capacity to cause agitation, aggression, and even violence. Drugs more frequently associated with violent events include ADHD medications such as methylphenidate, SSRIs such as paroxetine, SNRIs such as venlafaxine, mood stabilizers such as risperidone, as well as corticosteroids, oxycodone, and montelukast.3 Of these, the antidepressants are of greatest concern. They are frequently prescribed and, in addition to increasing the risk of violent behavior,29 are known to increase the risk of suicidality in individuals younger than 25 years of age.30 Given their serious risks and modest clinical effectiveness,31 the use of antidepressants in children and adolescents should be approached with great concern.

Final Thoughts

There is an increasing availability of specialty tests for the assessment of nutrient status and mental health parameters. Among them are urinary organic acids, urinary neurotransmitters, lymphocyte micronutrients, RBC fatty acids, and conventional serum nutrient tests. Given the complex and challenging nature of many mental health cases, it is sometimes tempting to put more and more weight on the results of these tests; however, in my opinion, all lab tests have their limitations and it is important to keep their role in context. For example, levels of urinary neurotransmitters or their metabolites reflect total body load, and may not accurately reflect CNS levels for a given patient.

Taking a thorough history, having a good working knowledge of the way that neurochemical imbalances manifest as symptoms, understanding the specific actions of the interventions we use, and keeping a close watch on how patients respond to treatments are the most important factors in the successful treatment of mental health conditions and, in particular, cases of aggression where the stakes are often higher. Although challenging, treating at-risk youth can be deeply rewarding and naturopathic medicine can provide a crucial role that is not being provided by any other facet of the healthcare system.

Sandro D’Amico, ND, graduated from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2002 and went on to complete his residency there. After that, he hightailed it back to the rolling hills of Northern California where he currently practices with his wife, Greta, at the Four Rivers Naturopathic Clinic in Auburn. Sandro has an unending passion for psychobiology and, in particular, how the structure and function of the brain and its interaction with our greater physiology shapes what it means to be human. This passion has led him to focus more and more on treating mental health conditions and psychological trauma.

Sandro D’Amico, ND, graduated from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2002 and went on to complete his residency there. After that, he hightailed it back to the rolling hills of Northern California where he currently practices with his wife, Greta, at the Four Rivers Naturopathic Clinic in Auburn. Sandro has an unending passion for psychobiology and, in particular, how the structure and function of the brain and its interaction with our greater physiology shapes what it means to be human. This passion has led him to focus more and more on treating mental health conditions and psychological trauma.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Youth Violence: Facts at a Glance. 2012. CDC Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/yv-datasheet-a.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2015.

- Hamilton SS, Armando J. Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(7):861-866.

- Moore TJ, Glenmullen J, Furberg CD. Prescription drugs associated with reports of violence towards others. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):1-5.

- Wohlfarth TD, van Zwieten BJ, Lekkerkerker FJ, et al. Antidepressants use in children and adolescents and the risk of suicide. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16(2):79-83.

- Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation—a possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289(5479):591-594.

- LeDoux J. The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious underpinnings of Emotional Life. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1996.

- Schore A. Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self: The Neurobiology of Emotional Development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1994.

- Rapp D. Is This Your Child? New York, NY: William Morrow & Company; 1991.

- Matthews J. Nourishing Hope for Autism. 3rd ed. Healthful Living Media; 2008.

- Virkkunen M, Rissanen A, Franssila-Kallunki A, Tiihonen J. Low non-oxidative glucose metabolism and violent offending: and 8-year prospective follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;168(1):26-31.

- Barzman DH, Patel A, Sonnier L, Strawn JR. Neuroendocrine aspects of pediatric aggression: Can hormone measures be clinically useful? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:691-697.

- Langevin R, Langevin M, Curnoe S, Bain J. The prevalence of thyroid disorders among sexual and violent offenders and their co-occurrence with psychological symptoms. Int J Prison Health. 2009;5(1):25-38.

- Trainor BC, Greiwe KM, Nelson RJ. Individual differences in estrogen receptor alpha in select brain nuclei are associated with individual differences in aggression. Horm Behav. 2006;50(2):338-345.

- Malik AI, Zai CC, Abu Z, et al. The role of oxytocin and oxytocin receptor gene variants in childhood-onset aggression. Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11(5):545-551.

- Valenta LJ, Elias AN, Eisenberg H. ACTH stimulation of adrenal epinephrine and norepinephrine release. Hormone Res. 1986;23(1):16-20.

- Glick AR. The role of serotonin in impulsive aggression, suicide, and homicide in adolescents and adults: a literature review. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;27(2):143-150.

- Hornboll B, Macoveanu J, Rowe J, et al. Acute serotonin 2A receptor blocking alters the processing of fearful faces in the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(10):903-914.

- Papakostas GI, Ongür D, Iosifescu DV, et al. Cholesterol in mood and anxiety disorders: review of the literature and new hypotheses. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14(2):135-142.

- Shrivastava S, Pucadyil TJ, Paila YD, et al. Chronic cholesterol depletion using statin impairs the function and dynamics of human serotonin(A1) receptors. Biochemistry. 2010;49(26):5426-5435.

- Fahrenholz F, Klein U, Gimpl G. Conversion of the myometrial oxytocin receptor from low to high affinity state by cholesterol. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;395:311-319.

- Zhang J, Muldoon MF, McKeown RE, Cuffe SP. Association of serum cholesterol and history of school suspension among school-age children and adolescents in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(7):691-699.

- Hibbeln JR, Ferguson TA, Blasbalg TL. Omega-3 fatty acid deficiencies in neurodevelopment, aggression and autonomic dysregulation: opportunities for intervention. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18(2):107-118.

- Meyer BJ, Byrne MK, Collier C. Baseline omega-3 index correlates with aggressive and attention deficit disorder behaviours in adult prisoners. PLoS One; 2015:10(6):e0129984.

- Frodl T, Szyf M, Carballedo A, et al. DNA methylation of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) is associated with brain function involved in processing emotional stimuli. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40(5):296-305.

- Russo AJ. Decreased zinc and increased copper in individuals with anxiety. Nutr Metab Insights. 2011;4:1-5.

- Chang MY, Tseng CH, Chiou YL. The plasma concentration of copper and prevalence of depression were positively correlated in shift nurses. Biol Res Nurs. 2014;16(2):175-181.

- Yorbik O, Olgun A, Kirmizigül P, Akman S. Plasma zinc and copper levels in boys with oppositional defiant disorder. [Article in Turkish] Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2004;15(4):276-281.

- Oliveira VA, Oliveira CS, Mesquita M, et al. Zinc and N-acetylcysteine modify mercury distribution and promote increase in hepatic metallothionein levels. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;32:183-188.

- Healy D, Herxheimer A, Menkes DB. Antidepressants and violence: problems at the interface of medicine and law. PLoS Med. 2006;3(9):1478-1487.

- Nischal A, Tripathi A, Nischal A, Trivedi JK. Suicide and antidepressants: what current evidence indicates. Mens Sana Monogr. 2012;10(1):33-44.

- Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47-53.