Prolotherapy

Regenerative Medicine

Fred G. Arnold, DC, NMD

Continuing in my series of articles on Regenerative Medicine, the topic of this article is prolotherapy. This technique is the first and oldest of the Regenerative Medicine treatments.

Prolotherapy is a safe, simple regenerative medicine injection treatment, and is probably one of the best kept secrets in Orthopedic Medicine. It stimulates the formation of healthy new tissue in both acute and chronic conditions. Many of the patients who come to our office stumble upon prolotherapy when they find it on the internet, or when a friend or relative refers them for prolotherapy. The term “prolotherapy” was first used by George S. Hackett, MD, in the 1950s. He defined it as “the rehabilitation of an incompetent structure by the generation of new cellular tissue.”1 The prefix “prolo” means “proliferate.” Dr Hackett and other doctors actually began injecting ligaments in the 1930s. Patients are surprised to learn that he conducted research, published articles, and authored a textbook on prolotherapy in 1956.1

How Does Prolotherapy Work?

When the prolotherapy solution is precisely injected into the site of pain or injury, prolotherapy creates a mild, controlled inflammation that stimulates the body to lay down collagen with the formation of new tendon, ligament, and cartilage, resulting in a strengthening of the weakened structure. This injection process stimulates the body’s natural wound repair process.2

Conditions Treated with Prolotherapy

There are a number of different musculoskeletal conditions that respond well to prolotherapy (Table 1):

Table 1. Common Conditions Treated with Prolotherapy

| Achilles tear | Hand pain & arthritis | Rotator cuff tears |

| Achilles tendonitis | Hip pain & arthritis | Rotator cuff tendonitis |

| Ankle pain & arthritis | Joint laxity | Sacroiliac joint pain |

| Ankle sprains | Knee pain & arthritis | Sciatica |

| Cartilage damage | Knee ligament injuries | Sprains & strains |

| Cervical radiculitis | Knee tendonitis | Spinal disc problems |

| Elbow pain & arthritis | Ligament tears | Tendonitis |

| Elbow tendonitis | Neck pain | Tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis) |

| Foot pain & arthritis | Patellar tendonitis | Thoracic pain |

| Golfer’s elbow (medial epicondylitis) | Plantar fasciitis | Wrist pain & arthritis |

Hackett Referral Patterns

In their book, Ligament and Tendon Relaxation, Treated by Prolotherapy,1Drs Hackett, Hemwall, and Montgomery provide detailed illustrations depicting how different ligaments show a reproducible pain pattern when stimulated or injured. And in The Art of Healing Injection Manual, Joel Baumgartner, MD, states, “These patterns are important when diagnosing and determining which structures need to be treated.”3 When an injection is performed on a tendon or ligament, pain may be experienced distal to the point of injection. The referral pattern of the pain can be found to correlate to the pain patterns diagramed by Dr Hackett. When the patient reports a ligament referral pattern during an injection, it is a positive indicator that the source of the patient’s pain is being treated.

Both Diagnostic and Therapeutic

According to Hackett, Hemwall, and Montgomery,1 most musculoskeletal pain is ligament pain, which occurs when tension on a ligament stretches the relaxed ligament fibers, resulting in abnormal tension and stimulation of the sensory nerves; this is because nerve fibers do not stretch. The validity of this statement and confirmation of the diagnosis can be made when injecting a local anesthetic solution within a ligament abolishes the pain.1

The therapeutic benefits of prolotherapy have been well documented in the literature for a wide variety of musculoskeletal conditions:

- Hooper and Ding conclude that dextrose prolotherapy appears to be a safe and effective method for treating chronic spinal pain.4 In their study utilizing prolotherapy, 91% of patients reported a reduced level of pain, 84% of patients reported improvements in activities of daily living, and 84.3% reported improvements in ability to work.”4

- In a study involving 29 patients, prolotherapy proved effective and satisfactory in 83% of the patients, as demonstrated by clinically significant improvements in shoulder pain due to ligamentopathy.5

- In another study, 52 adults with painful knee osteoarthritis for at least 3 months were randomized to intra- and peri-articular injection groups. The authors concluded that dextrose prolotherapy could be an inexpensive and effective way to manage knee osteoarthritis.6

Numerous other studies validating the effectiveness of prolotherapy are available on the internet in PubMed and in the Journal of Prolotherapy.

Prolotherapy Solution

Over the decades a number of different prolotherapy solutions have been used to stimulate the inflammatory wound repair response. Some of these solutions include sodium morrhuate (no longer commercially available), phenol, glycerin, testosterone, zinc sulfate, and pumice.

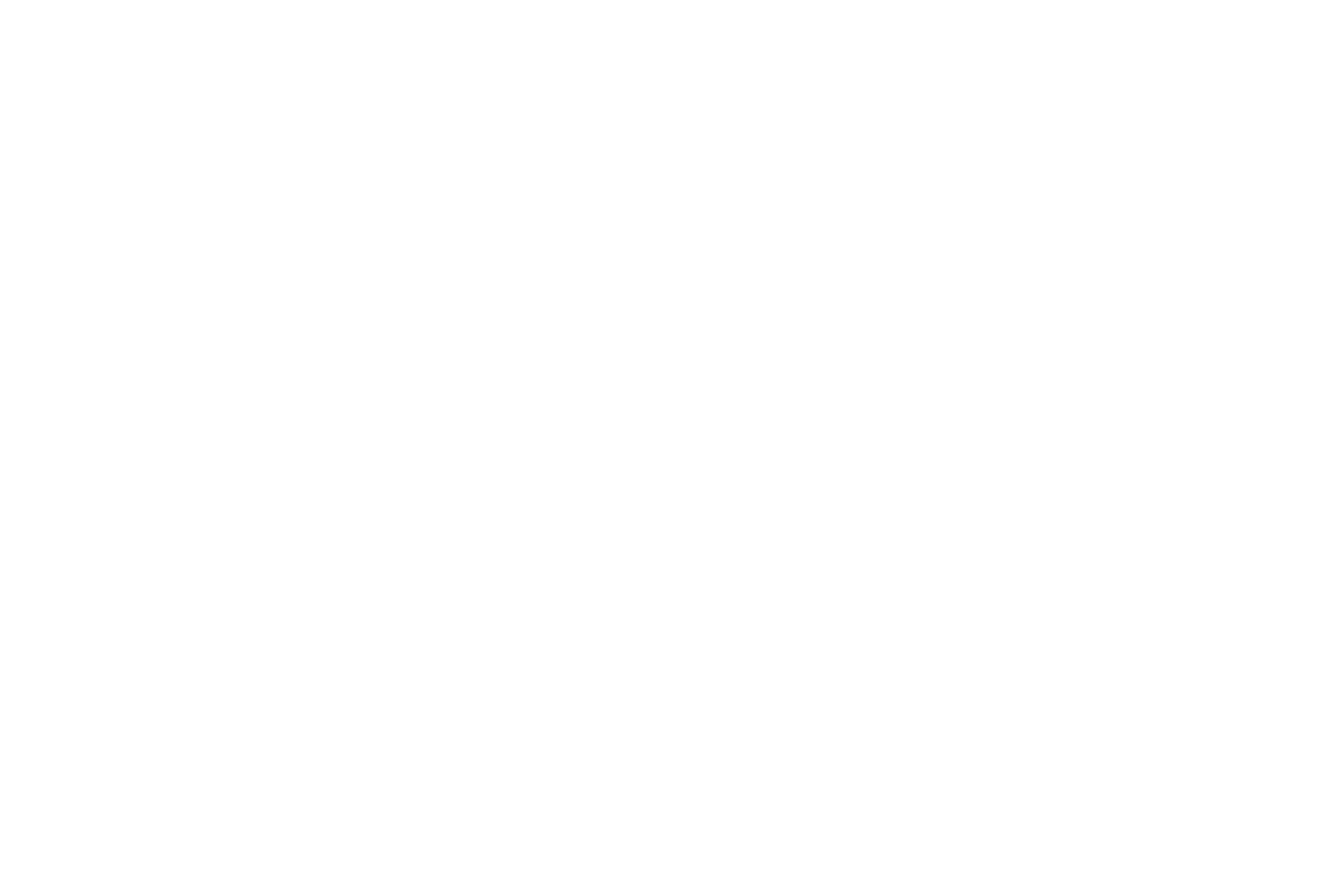

An injection solution commonly used in practice today includes a mixture of dextrose (sugar solution), lidocaine (anesthetic), and vitamin B12 (Figure 1). This hypertonic solution varies in the amount of dextrose used for different body parts.

Figure 1. Prolotherapy Solution

(Combination of dextrose, lidocaine, methylcobalamin)

Patient Selection & Evaluation

Prolotherapy is not a cure for all painful musculoskeletal conditions. Each patient must be evaluated on an individual basis with a through history, physical exam including relevant orthopedic tests, and diagnostic testing. Pre-treatment diagnostic testing may include X-rays, MRIs, ultrasound evaluation, and full laboratory work-up.

The case history listed next is an example of a person who would not benefit from prolotherapy.

Case History: Shoulder

The patient is an 80-year-old male who was exercising with weights at the gym, when he experienced pain in his left shoulder. He felt he may have injured his shoulder, as he had before with his right shoulder. His examination revealed normal range of motion; however, he had 0/4 strength on the Supraspinatus Press Test as well as Jode’s Test (empty-can test), indicating a possible supraspinatus tendon tear. There was no visible edema or swelling of the shoulder, but he was very tender at multiple points on the rotator cuff.

The ultrasound picture of the initial injury (Figure 2) shows a long axis view of the patient’s shoulder in a half Crass position with resistance. The picture clearly shows the “bird’s beak” view of the supraspinatus tendon, with tears in the tendon along the footprint of attachment on the humerus. The tendon should not show the blackened or hypoechoic nature, as it indicates a tear. The patient was sent for an MRI of the shoulder, and the radiologist report read, “No full-thickness rotator cuff tear. Focal low-grade partial-thickness bursal sided tear of the supraspinatus tendon.” I felt this was an underestimation of the patient’s condition. When I called to speak to the radiologist and sent him a copy of this ultrasound picture, he amended his report to say “INTERMEDIATE grade bursal sided tear of the lateral supraspinatus tendon, involving 50% of the tendon thickness.” I still felt this was an underestimation of the patient’s condition.

Figure 2. Ultrasound: Initial Injury

Although, the patient was explicitly told to be very careful in how he used his shoulder and to avoid any strenuous use of his shoulder, he got in the swimming pool with his grandchildren and hurt his shoulder again.

Although, the patient was explicitly told to be very careful in how he used his shoulder and to avoid any strenuous use of his shoulder, he got in the swimming pool with his grandchildren and hurt his shoulder again.

In the ultrasound picture of the second injury (Figure 3), there is no doubt that a full thickness tear of the supraspinatus tendon now exists. The dark area above the humerus represents fluid, and we no longer see the supraspinatus as we did previously. Visualization of the shoulder shows the humeral head displaced inferiorly, as well as edema of the anterior aspect of the shoulder. The patient was unable to raise his shoulder in flexion and abduction, and he reported pain at rest and with movement. The patient was referred to an orthopedic surgeon.

Figure 3. Ultrasound: Second Injury

The ability to view anatomical structures in “real time” motion is a distinct advantage of ultrasound over MRI. The lessons from this story include the following:

- Do not always trust the results of an MRI

- Always perform a targeted case history for a new injury

- Always perform a physical exam on a patient

- Always re-evaluate if a new injury occurs

- Refer to the appropriate source if you cannot help the patient

- Ultrasound evaluation allows dynamic evaluation for proper diagnosis and treatment

Contraindications for Prolotherapy

Absolute contraindications for prolotherapy include acute infections (such as cellulitis), acute fractures or dislocations, local abscess or septic arthritis, allergies to injectants, and prosthetic joints. Relative contraindications include consistent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) within 48 hours, local injection or systemic use of corticosteroids within 2 weeks, acute gouty arthritis, acute fracture, use of blood thinners, with INR (International Normalized Ratio) greater than 3.7, 8

Learning Prolotherapy

It is beyond the scope of this article to teach the reader how to perform prolotherapy. Since prolotherapy is a procedure, it also cannot be learned by simply reading a textbook. It is critical that the beginning prolotherapist have a firm background of human anatomy – starting with all the joints and their associated ligaments, muscles, and tendons – since these are the actual structures that will be injected. Palpation is essential to developing good prolotherapy skill and achieving optimum results. The prolotherapy doctor should always palpate the area to be injected and should know the named anatomical structures that will be injected. The practitioner should be able to visualize the treatment area before the injection needle is actually placed through the skin.

Some of the more commonly recognized organizations that teach prolotherapy include the American Osteopathic Association of Prolotherapy Regenerative Medicine, the American Association of Osteopathic Prolotherapy, and the Hackett Hemwall Pederson Foundation. These organizations allow naturopathic physicians to attend their training courses; however, they are not allowed to attend their training excursions to other countries.

The Neil Riordan Regenerative Medicine Center at Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (SCNM) offers prolotherapy training to doctors that includes both lecture and “hands-on” injection experience.

The naturopathic doctor who wishes to implement prolotherapy should be willing to attend these conferences and also to study with experienced physicians who practice prolotherapy.

Ultrasound

Prolotherapy regenerative joint injections may be performed with ultrasound guidance. This allows for exact visual identification of the treatment area and placement of the solution. Ultrasound is not a substitute for palpation skills, which will help the practitioner more accurately locate the area to be visualized with the ultrasound probe.

Summary

Prolotherapy is a safe, natural, non-drug, non-surgical treatment that has the unique ability to directly address the cause of musculoskeletal pain by repairing weakened joints. The practitioner should have an in-depth knowledge of anatomy and have taken the time to develop his or her palpation skills. When the prolotherapy solution is precisely injected into the site of pain or injury, prolotherapy creates a mild, controlled inflammation that stimulates the body to lay down collagen with the formation of new tendon, ligament, and cartilage, resulting in a strengthening of the weakened structure. There are a number of different training opportunities available to the practitioner, to develop and hone their skills. The use of ultrasound can help in the diagnosis as well as guide exact needle placement for the prolotherapy solution. When prolotherapy is provided by an experienced clinician, surgery is often not needed, rehabilitation time is shortened, and the patient is able to reduce or discontinue prescription pain medications.

References:

- Hackett GS, Hemwall GA. Montgomery GA. Ligament and Tendon Relaxation: Treated by Prolotherapy. 5th Edition. Oak Park, IL: Beulah Land Press; 2002: xix, 13, 26-36.

- Ravin TH, Cantieri MS, Pasquarello GJ. Principals of Prolotherapy. Denver, CO: American Academy of Musculoskeletal Medicine; 2008: 15-21.

- Baumgartner JJ. Prolotherapy: The Art of Healing: Complete Injection Manual. 3rd Edition; Waite Park, MN: Rejuvmedical; 2011.

- Hooper RA, Ding M. Retrospective case series on patients with chronic spinal pain treated with dextrose prolotherapy. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(4):670-674.

- Jo DH, Ryu KA, Yang SJ, Kim MH. Clinical Study: Effects of Prolotherapy in Patients with Shoulder Pain. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2004;46(5):589-592.

- Farpour HR, Fereydooni F. Comparative effectiveness of intra-articular prolotherapy versus peri-articular prolotherapy on pain reduction and improving function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. Electron Physician. 2017;9(11):5663-5669.

- Rabago D, Slattengren A, Zgierska A. Prolotherapy in primary care practice. Prim Care. 2010:37(1):65-80.

- Zaharoff A. Introduction to Prolotherapy: Safe, Simple, Effective, Elegant. [Presentation]. Research Symposium: The Anatomy, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Chronic Myofascial Pain with Prolotherapy. October 17-19, 2019. Madison, WI.

Fred G. Arnold, DC, NMD, specializes in Regenerative Joint Injections and has over 29 years of clinical experience. Dr Arnold is certified in prolotherapy by the American Association of Orthopedic Medicine (AAOM). He is also a Fellow in both the Anti-Aging & Regenerative Medicine and the American Academy of Ozonotherapy (FAAOM). Dr Arnold has degrees in both naturopathic medicine and chiropractic.

Fred G. Arnold, DC, NMD, specializes in Regenerative Joint Injections and has over 29 years of clinical experience. Dr Arnold is certified in prolotherapy by the American Association of Orthopedic Medicine (AAOM). He is also a Fellow in both the Anti-Aging & Regenerative Medicine and the American Academy of Ozonotherapy (FAAOM). Dr Arnold has degrees in both naturopathic medicine and chiropractic.