Tick Tubes: Stopping Lyme in Its Tracks

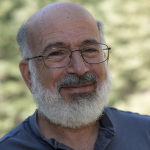

JACOB SCHOR, ND, FABNO

This past winter, my wife and I saved all the cardboard tubes at the core of toilet paper and paper towel rolls. Today (early March), I will use them to make “tick tubes.” Our nearest neighbor, a now-retired gynecologist, has already put his tubes out, and I’m aware of not keeping up. He turned me onto this idea during the winter when he shared a link to a 2018 post by Erin Huffstetler, a woman who writes about how to live frugally.1

Making tick tubes is simple enough, though the concept behind it requires a bit more explaining. Tick tubes are all about preventing Lyme disease. It’s a method we’d heard about but had little experience with, having spent the last 30 years living in Colorado. Some colleagues tell me that Lyme disease is endemic in our Rocky Mountain state, but I was not convinced of that in my practice. I can count the patients over the years who presented with the classic Lyme bull’s-eye tick-bite rash, and though this telltale sign is only present in a fraction of cases, all of those patients had recently returned from states where Lyme disease is truly rampant.

Looking at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s map of Lyme cases,2 it’s clear that our cabin in Maine – where we holed up during the pandemic – is located deep in an area where Lyme disease is ubiquitous. Worrying about ticks is a new worry for us – something to add to our lengthening list of existential threats. I became interested in tick tubes when I learned they could potentially reduce tick populations in the areas where you place them. It’s that “act locally” idea that we talk about. But the concept was new to me, and we were a bit behind in stockpiling those empty tubes.

There’s a conspiracy theory out there that Lyme disease was created by our own government as part of a germ warfare effort and that it escaped from a secret laboratory on Plum Island, to reach Lyme, Connecticut, in 1976. This is more proof how much humans crave the titillation of secret plots and cover-ups, whether true or not. It’s no news these days that falsehoods spread faster and wider than the truth. Far less salacious is the Yale University research reporting that the Lyme disease bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi, is ancient in North America and has circulated in forested regions for at least 60 000 years, way before humans arrived on the scene.3 The recent emergence of Lyme disease at current rates is the result of forest fragmentation and the population explosion of white-tailed deer in the last century.3 This combination set up optimal conditions for the spread of ticks and this current Lyme epidemic.

Since Lyme was first described, it has spread across New England to the Midwest. Yearly reported cases have tripled since 1995,4 and the CDC estimates that more than 300 000 Americans get infected each year.5

A Tick’s Life Cycle

Ixodid ticks – the ones that give us Lyme disease – have 3 parasitic stages: larva, nymph, and adult. At each of these stages, the tick must find a blood meal in order to develop into their next life-stage or, in the case of the adults, to reproduce.6 Eggs laid by an adult hatch into tiny larvae (<0.9 mm), about the size of the period at the end of a sentence (depending on font size). To get that needed blood meal, these larvae latch onto mice or chipmunks. (A single mouse might carry 300-400 tick larvae.) As the larvae feed on these little rodents, they acquire the pathogens that cause Lyme, babesiosis, anaplasmosis, and other diseases. The rodents are unaffected by these illnesses. In the spring and early summer, the larvae become nymphs that are relatively large, about the size of a poppy seed. That’s when they seek another blood meal, this time from larger mammals, such as deer, pets, or people.7 That’s how we get infected.

If a person wants to eliminate ticks on their property, it’s smart to interrupt the ticks’ life cycle in the early phase of their development while they’re still small enough to hitch a ride on mice or chipmunks. There are several ways to do this.

Tick-Targeting Strategies

The standard approach to eliminating ticks has been to spray outdoor areas with acaricides, which are heavy-duty pesticides. While this is effective and reliable, public acceptance of this toxic approach has been less than full. Alternative approaches have gained favor. The 2 most accepted methods attack disease transmission when the ticks are still in that early stage of development. One is sold as a proprietary Tick Box, and the other is sold as proprietary Tick Tubes.

The Tick Box consists of a baited box that attracts rodents and then coats their fur with a pesticide (0.75% fipronil). Design of these bait boxes has improved over the years. The bait in early models attracted not only mice, but also squirrels; a study examining an improved model showed that as many as 92% of the tick boxes were destroyed by grey squirrels.8 They also had to be child-proofed (though I’ve found no statistic on how many children attacked the bait or whether this requirement was inspired by fear of lawyers). A baited and much improved 2012 model is reported effective at reducing tick levels in an area; tick nymph populations can drop by 80-90%.8

The commercial Tick Tube products are much simpler and less toxic than the boxes. The earliest report I’ve found examining their effectiveness is from 1991.9 However, one can make a fair imitation of the commercial version in only a few minutes at home, as they are simply paper tubes stuffed with cotton that has been pretreated with pyrethrins. These are the insecticidal compounds found naturally in certain plants, including Tanacetum cinerariifolium and Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium (common name, pyrethrum).10 Synthetic forms of this chemical are technically called “pyrethroids,” but this convention isn’t closely followed. Rodents love cotton; when they stumble across it during their wanderings, they’ll collect it and bring it home to line their nests. The pyrethroid-infused cotton lining the nest kills any tick nymphs that the mice might have acquired in their travels, while simultaneously treating any nest mates.

Both systems work. The boxes are reported to be more effective,11 but the tubes are less expensive, less toxic, and are biodegradable. The real advantage of the tubes is that they are as simple as pie to make, and one can make them at home with stuff that would normally be headed to the dump (Figure 1). Some online websites suggest saving lint from your clothes dryer to use. If you don’t have lint available, cotton balls can be used. Anyone who lives in Lyme country probably already has a spray bottle of pyrethroids around the house for spraying their shoes and pants cuffs as a way to dissuade ticks from crawling up their legs. We certainly do.

Figure 1. Tick Tube Makings

These tick tubes get placed strategically around the yard, along rodent corridors (mice like to run with their whiskers grazing a wall), wood piles, and places sheltered from rain (so they don’t biodegrade faster than need be). Knowing that our dear neighbor has already set out his tick tubes is making me pick up the pace a bit. One must keep up with one’s neighbors.

Stopping Lyme Before It Starts

It’s not just the simplicity of this approach that makes it appealing; it’s also the strategy of leveraging knowledge of the life-cycle of the vectors that have turned this old disease into a widespread epidemic in regions of our country. It’s using an understanding of biology to advance public health. I see this as a truly naturopathic approach to Lyme disease, where the focus is on prevention rather than treatment. I am hesitant to actually say this, though; I’ve never heard mention of either tick boxes or tick tubes by colleagues who are focused on Lyme. Instead, I’ve heard lots about antibiotics and the necessity of treating Lyme patients with IVs, an approach that still seems incongruent with my old-school naturopathic training – something that might be best left to allopathic doctors and their worldview of attacking disease with drugs.

Granted, I’m new to worrying about Lyme disease, and perhaps this approach of targeting juvenile ticks is much less effective than the scientific literature suggests. Or perhaps everyone is already doing this, and I just haven’t been clued in yet. Even if tick tubes work only half as well as researchers claim, using them is better than doing nothing, and as far as I can calculate, it’s going to cost me pennies to try. What’s the downside of investing a little time to lower risk of disease? None that I can think of.

References:

- Huffstetler E. How to Make Tick Tubes. March 2, 2018. Available at: https://www.myfrugalhome.com/how-to-make-tick-tubes/. Accessed March 5, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme and Other Tickborne Diseases Increasing. Last reviewed April 22, 2019. CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/media/dpk/diseases-and-conditions/lyme-disease/index.html. Accessed March 5, 2021.

- Walter KS, Carpi G, Caccone A, Diuk-Wasser MA. Genomic insights into the ancient spread of Lyme disease across North America. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1(10):1569-1576.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme and Other Tickborne Diseases Increasing. Last reviewed April 22, 2019. CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/media/dpk/diseases-and-conditions/lyme-disease/index.html. Accessed March 5, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How many people get Lyme disease? Last reviewed January 13, 2021. CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/humancases.html. Accessed March 6, 2021.

- Kleinjan JE, Lane RS. Larval keys to the genera of Ixodidae (Acari) and species of Ixodes (Latreille) ticks established in California. Pan-Pac Entomol. 2008;84(2):121-142.

- Consumer Reports. How to get rid of ticks in your yard. August 3, 2015. Available at: http://www.tickboxtcs.com/ConsumerReports/. Accessed March 5, 2021.

- Schulze TL, Jordan RA, Williams M, Dolan MC. Evaluation of the SELECT Tick Control System (TCS), a Host-Targeted Bait Box, to Reduce Exposure to Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in a Lyme Disease Endemic Area of New Jersey. J Med Entomol. 2017;54(4):1019-1024.

- Stafford KC 3rd. Effectiveness of host-targeted permethrin in the control of Ixodes dammini (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1991;28(5):611-617. Erratum in: J Med Entomol. 1992;29(2):376.

- ScienceDirect. Pyrethrum. [Misc. abstracts]. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/pyrethrum. Accessed July 7, 2021.

- Jordan RA, Schulze TL. Availability and Nature of Commercial Tick Control Services in Three Lyme Disease Endemic States. J Med Entomol. 2020;57(3):807-814.

Jacob Schor, ND, FABNO graduated from NCNM in 1991 and has practiced in Denver, CO, ever since. He has been active in state association politics, taking his turn as president of the Colorado Association of Naturopathic Doctors and Legislative Chair. Dr Schor has also held leadership positions in the Oncology Association of Naturopathic Physicians, served on the AANP Board of Directors, and chaired the AANP’s speaker selection committee. For the past decade he has been the Associate Editor of the Natural Medicine Journal, and is a regular contributor to the Townsend Letter.