Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema

Jessica Moore, ND

Heather Paulson, ND, FABNO

While breast cancer continues to be the most common type of cancer in women in the United States, breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) is only recently recognized as a public health issue deserving greater attention. It has been identified as a significant survivorship issue in women treated with surgery and radiation for breast cancer. These patients are considered to be at a lifetime risk of developing lymphedema (LE); however, early detection and prompt intervention has been reported to reduce LE-associated complications.1 Quality of life may be affected through physical distress, functional impairment, and psychosocial and economic factors.2-4 Integrative care may benefit patients with BCRL through a multifaceted approach, enhanced individualization of treatment protocols, compassionate care, and frequent monitoring.5,6

Background

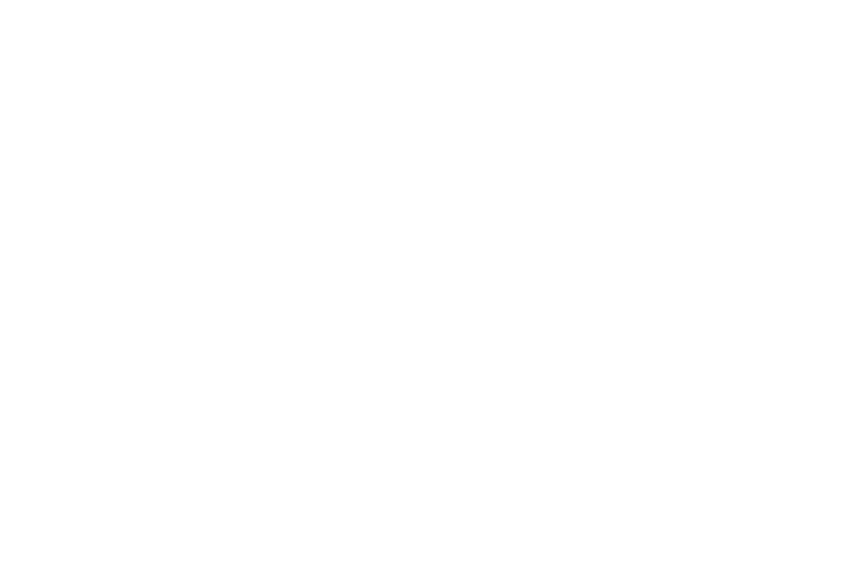

Obstruction of lymphatic drainage results in edema with a high concentration of protein. This may lead to a distortion in fluid balance, impaired transportation of lipids, and/or compromised immune function. Local cell death can occur within 24 hours, and the protein-rich fluid also serves as an excellent medium for bacteria, increasing the risk of cellulitis, lymphangitis, lymphatic sclerosis, and even sepsis. While the most common cause of secondary LE worldwide is lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis), in developed nations secondary LE is most commonly caused by mechanical insufficiency due to tumor, trauma, surgery, radiation, or infection.7,8 Figure 1 denotes the normal flow and anatomy of the lymphatic system. Treatment for breast cancer can disrupt this system at any point.

Secondary Lymphedema & Breast Cancer

The risk of BCRL is highest among those who have been treated with both radiation and surgery, who are obese, and who had a greater number of lymph nodes removed during surgery. Other common risk factors include tumor location (upper outer quadrant), infection, trauma, hormonal therapy, large breast size, and chemotherapy.2-4 Complete axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) may be a necessary treatment for regional lymph node metastasis. Of course, sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy for staging of breast cancer has significantly decreased the incidence of ALND in patients with sentinel lymph nodes that do not harbor metastases.2 Newer surgical studies are now looking at axillary reverse mapping in an attempt to preserve lymphatic drainage in either SNL biopsy or ALND. In any case, there is still a risk of LE even after simple operations.3,6

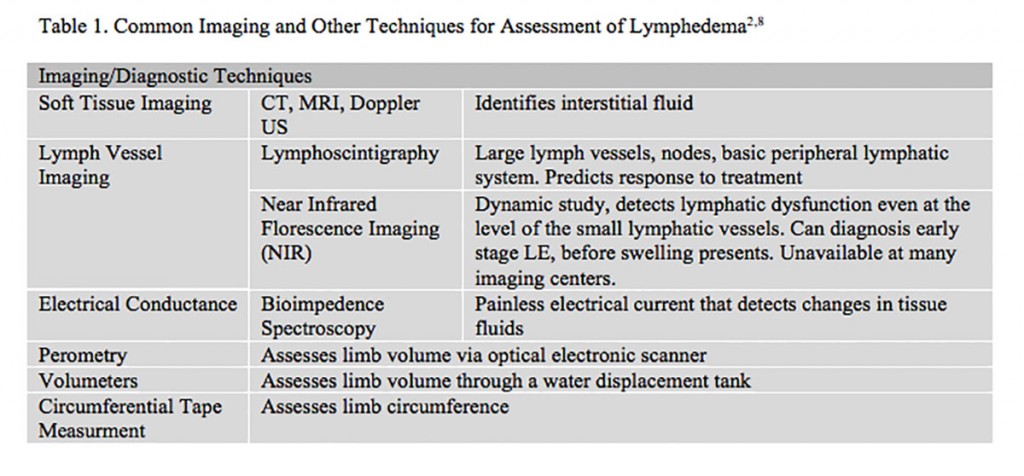

In breast cancer, the areas most likely to become edematous are the upper limb, breast, and chest. Impaired limb mobility, discomfort, pain, and psychological distress are the most common clinical features. Other symptoms may include, but are not limited to, the following: sensation of heaviness, fullness or tightness, skin discoloration, thickening or dryness of the skin, and decreased immune activity in the affected area.4 It is possible to have symptoms of pain or heaviness without limb edema. Early lymphatic edema most often presents as non-pitting edema, as it is confined to the subcutaneous space. Late stages of LE may involve pitting edema. Systemic conditions, vascular edema, thrombosis, and infection must be ruled out before a diagnosis of BCRL is considered. While history and physical exam are an acceptable method of diagnosis, imaging techniques may also be utilized (Table 1). It is critical to remember that LE may coexist with other medical/edematous conditions and that effective treatment of LE is based on an accurate and early diagnosis of LE. Diagnosis should be made by a practitioner who has training and experience with LE.8

Screening and measurement for early detection of BCRL is recommended for all patients diagnosed and treated for breast cancer.1-8 This may include pre-treatment measurements of both arms and then post-treatment measurements at regular follow-up intervals. Diagnosis and follow-up may also assign a clinical stage (0-3) and grade (1-4), which are based on changes in biomechanical tissue properties including, size, volume, presence of pitting, tissue texture, enlarged skin folds, wounds, skin alterations, and papillomas.

Individual Differences

Not all individuals who undergo surgery, node dissection, malignancy, radiotherapy, or other lymphatic insult will develop LE. Incidence has been reported between 3% and 87% in various studies.9 New genetic research suggests that individuals with LE lack compensatory mechanisms necessary to prevent the development of LE.It has been postulated that mutations or variations in the genes, such as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 or the VEGF-C/VEGFR3 signaling systems, may increase the risk of secondary LE. Other lymphatic and angiogenic genes have also been recently implicated.9

There is a component of individuality with regard to the capacity for compensation by collateral flow, regeneration of damaged lymphatics, and risk of complication from LE. Lifestyle, education on preventative care for LE, frequent monitoring, and hygiene are also important individualizing prognostic factors.

Treatment

Regular exercise, pre-surgery LE education, and patient-empowered self-care prevention activities are associated with a better prognosis in BCRL.10 Treatments should be started early and be specific to the individual, their physiology, and resources. Untreated or poorly managed LE will result in the accelerated progression of fibrosis and deposition of adipose tissue into the affected area, as well as increase a patient’s risk for complications such as cellulitis or other infection.2,7

Conventional Management

Physicians will commonly refer patients to LE specialists for management, education, and monitoring. Complete decongestive therapy (CDT) is considered the current standard of care for managing LE. This non-invasive therapy includes manual lymphatic drainage, compression therapy, therapeutic exercise, and skin/nail care. Surgery is usually only considered when other therapies have failed, and must be done in conjunction with CDT. Surgical options include debulking surgery, liposuction, tissue transfers, and microsurgical lymphatic reconstruction.7,8 Diuretics are not effective and tend to dehydrate the patient, since they do not remove the high protein concentration along with the excess water content. Benzopyrones (medications that reduce vascular permeability) are reported to be somewhat effective, but are not used in North America for treatment of LE.2 Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used in the case of cellulitis or lymphangitis (to reduce the risk of sepsis), and long-term prophylactic antibiotics are sometimes used in patients with recurrent infection.

Naturopathic Therapies

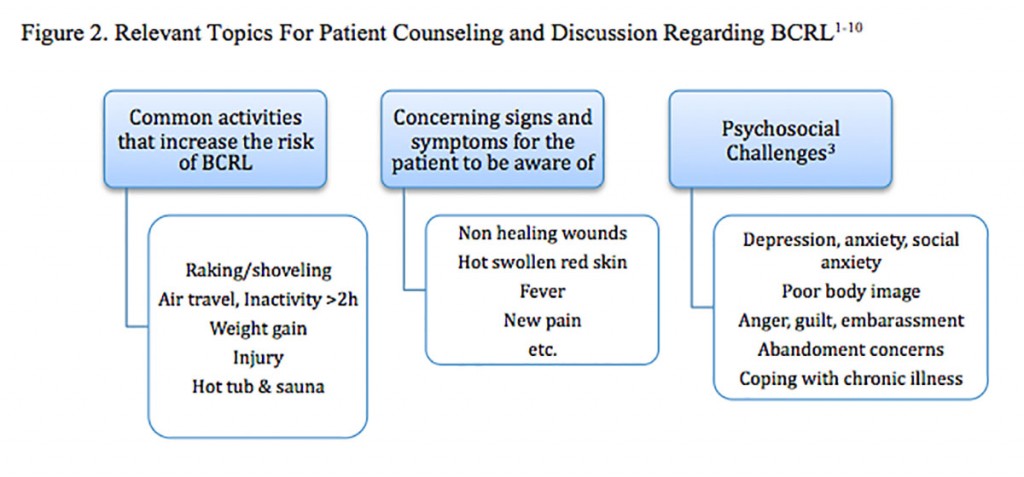

Patient education, empowerment and frequent monitoring are critical to the successful management of BCRL. Many naturopathic practitioners may want to work collaboratively with a LE specialist. Patients should be counseled on the topics listed in Figure 2. Since obesity is a major risk factor, naturopathic recommendations for diet, sleep, exercise, and lifestyle with regard to weight management may be valuable, in general, as well as before and after radiation and or surgery.11

While CDT is considered the gold standard of care, it is an intense treatment regimen requiring time and significant medical care costs, and does not typically completely reduce limb volume.2,7 Research on naturopathic therapies and modalities for BCRL is sparse, but promising. For example, a 2013 publication in the journal Cancer is one of several studies providing good evidence for the use of acupuncture in BCRL. Acupuncture was administered for 30 minutes, twice per week for 1 month. It was found to be safe and effective, significantly reducing arm circumference. Although the protocol was not individualized, it was still found to be highly effective. The point protocol was targeted towards reducing dampness and is listed as follows: TE-14, LI-15, LU-5, CV-12, CV-3, LI-4, ST-36, SP-6. Several studies recognize that it is important to avoid puncturing an affected area or limb, especially given the increased risk for infection in LE. Use of the contralateral area or limb is indicated instead.12-14

Clinical note: Similarly, any puncture of the skin of the ipsilateral extremity should be avoided, including finger-prick glucose testing and blood draws, etc.

Low-level laser therapy (Riancorp LTU-904 laser therapy) was FDA-approved in 2006 for post-mastectomy LE. “Low Intensity” means wavelengths between 650 and 1000 nmol. This therapy is administered in either a scanning or spot-laser application. The proposed mechanism of action is encouragment of lymphangiogenesis, lymphatic motricity, and stimulation of macrophages.15

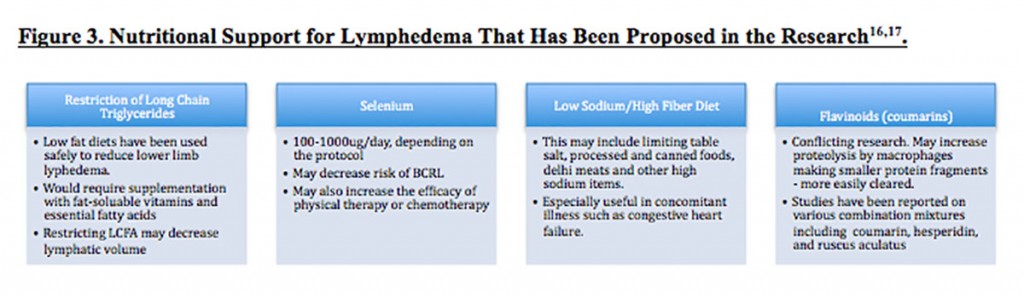

Nutritional support and dietary restrictions have been proposed, although evidence is minimal (Figure 3). Testing for B vitamin and folate levels might be considered, as deficiencies in these nutrients are associated with increased capillary permeability (in conditions such as beriberi). Cancer, anorexia, birth control and other hormone therapies can be associated with these deficiencies.16

Botanical medicines such as Aesculus hippocastanum have been also proposed; however, it is more often suggested for venous edema and not LE.7 It may be indicated if trauma or other concomitant conditions such as heart failure are affecting the LE picture. It is, however, a coumarin-containing botanical. Interestingly, in a rat study, coumarin proved to be a “highly active therapeutic agent against avitaminosis-aggravated lymphedema.” Perhaps another reason to test for vitamin deficiencies?17

Local hyperthermia has been discussed in a few studies and noted for significant reductions in limb volume in lower leg edema. In a study looking at upper and lower leg lymphedema with or without lymphangitis, all 67 patients improved, with a marked regression in 55/67 patients. The interior of the hyperthermia chamber heats the affected limb to 41°C, with 80% humidity. Patients completed 4 to 5 daily applications (each 45 minutes in duration), every 15 days for 6 months.18 A drawback of this therapy is that it requires specific equipment and training, and is time-involved.

Aqua lymphatic therapy has been proposed as a therapy for women with mild-to-moderate BCRL. This therapy has been administered successfully in trials done in a group setting in a pool, for 45 minutes once per week. It involves breathing exercises, proximal movements of the chest and shoulder girdle, self-massage, and specific positioning of the arm. The resistance from the water is proposed to strengthen muscles, improve lymphatic clearance, and influence the direction of lymphatic flow.19

Many breast cancer survivors will alter their arm and upper body activities in fear of the possibility that they may develop LE. Contrary to this fear, studies suggest that carefully-administered slowly-progressive weight-lifting is associated with a decrease in arm swelling in breast cancer survivors. A study involving 134 participants concluded that even when up to 5 axillary nodes were removed in breast cancer treatment, there was no increase in LE associated with weight lifting, and that appropriate weight-lifting may lead to a reduction in incidence and severity of BCRL.20

Chronic LE poses a risk of permanent fibrosis. Naturopathic therapies targeted towards oxygenating tissues, decreasing free radical production, modulating inflammatory cytokines, and enhancing detoxification could be useful in preventing or decreasing the risk/rate of permanent fibrosis associated with BCRL, although further studies are required.12 Other therapies mentioned in the literature are hyperbaric oxygen, qi gong, yoga, mind-body therapies, and other nutritional or botanical therapies.

Conclusion

It is crucial for healthcare practitioners, patients, and their caregivers to remember that BCRL can present at any time after treatment for breast cancer. Since there is significant heterogeneity regarding both the incidence and symptom presentation of BCRL, addressing the special needs of each patient is an important area for integrative practitioners, including naturopathic doctors.

References:

- Meneses KD, McNees MP. Upper extremity lymphedema after treatment for breast cancer: a review of the literature. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2007;53(5):16-29.

- Sakorafas GH, Peros G, Cataliotti L, Vlastos G. Lymphedema following axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. Surg Oncol. 2006;15(3):153-165.

- Hayes SC, Janda M, Cornish B, et al. Lymphedema after breast cancer: incidence, risk factors, and effect on upper body function. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3536-3542.

- Cormier JN, Askew RL, Mungovan KS, et al. Lymphedema beyond breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cancer-related secondary lymphedema. Cancer. 116(22):5138-5149.

- Lee BB, Bergan J, Rockson SG, eds. Lymphedema: A Concise Compendium of Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2011.

- Papadopoulou MC, Tsiouri I, Salta-Stankova R, et al. Multidisciplinary lymphedema treatment program. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2012;11(1):20-27.

- Horning KM, Guhde J. Lymphedema: an under-treated problem. Medsurg Nurs. 2007;16(4):221-227.

- Position Statement of the National Lymphedema Network. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Lymphedema. Updated February, 2011. National Lymphedema Web site. http://www.lymphnet.org/pdfDocs/nlntreatment.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2013.

- Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Paul SM, et al. Lymphatic and angiogenic candidate genes predict the development of secondary lymphedema following breast cancer surgery. PloS One. 2013;8(4):e60164.

- Chiefetz O, Haley L, Breast Cancer Action. Management of secondary lymphedema related to breast cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(12):1277-1284.

- Shaw C, Mortimer P, Judd PA. A randomized controlled trial of weight reduction as a treatment for breast cancer-related lymphedema. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1868-1874.

- Cassileth BR, Van Zee KJ, Yeung KS, et al. Acupuncture in the treatment of upper-limb lymphedema: results of a pilot study. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2455-2461.

- Cassileth BR, Van Zee KJ, Chan Y, et al. A safety and efficacy pilot study of acupuncture for the treatment of chronic lymphoedema. Acupunct Med. 2011;29(3):170-172.

- de Valois BA, Young TE, Melsome E. Assessing the feasibility of using acupuncture and moxibustion to improve quality of life for cancer survivors with upper body lymphoedema. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(3):301-309.

- Ahmed Omar MT, Abd-El-Gayed Ebid A, El Morsy AM. Treatment of post-mastectomy lymphedema with laser therapy: double blind placebo control randomized study. J Surg Res. 2010;165(1):82-90.

- Foldi-Borcsok E, Foldi M. Lymphedema and vitamins. Am J Clin Nutr. 1973;26(2):185-190.

- Gaby A. Nutritional Medicine. Concord, NH: Fritz Perlberg Publishing; 2011.

- Campisi C, Boccardo F, Tacchella M. Use of thermotherapy in management of lymphedema: clinical observations. Int J Angiol. 1999;8(1):73-75.

- Tidhar D, Katz-Leurer M. Aqua lymphatic therapy in women who suffer from breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema: a randomized controlled study. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(3):383-392.

- Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, et al. Weight lifting for women at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema. JAMA. 2010;304(24):2699-2705.

*****

Jessica Moore, ND, graduated as a naturopathic doctor in 2013 from the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine. She holds a Bachelor of Kinesiology degree from the University of Calgary and has recently accepted a position as a 1st-year resident with Cancer Treatment Centers of America. As a passionate student of the art and science of naturopathic medicine, Jessica believes that research is an important contribution to naturopathic medical practices today.

Jessica Moore, ND, graduated as a naturopathic doctor in 2013 from the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine. She holds a Bachelor of Kinesiology degree from the University of Calgary and has recently accepted a position as a 1st-year resident with Cancer Treatment Centers of America. As a passionate student of the art and science of naturopathic medicine, Jessica believes that research is an important contribution to naturopathic medical practices today.

Heather Paulson, ND, FABNO, is a Fellow of the American Board of Naturopathic Oncology (FABNO), which represents an expertise in the area of naturopathic oncology. After graduating from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (SCNM), Heather furthered her training at IU Goshen Health System for 2 years as an oncology specialty resident. Dr Paulson is in private practice at Arizona Natural Health Center and has an oncology-focused practice that brings together the best of natural therapies for cancer care. Dr Paulson enjoys sharing her naturopathic oncology passion by teaching oncology at SCNM. You can reach Heather Paulson at www.aznaturalhealth.com or [email protected].

Heather Paulson, ND, FABNO, is a Fellow of the American Board of Naturopathic Oncology (FABNO), which represents an expertise in the area of naturopathic oncology. After graduating from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (SCNM), Heather furthered her training at IU Goshen Health System for 2 years as an oncology specialty resident. Dr Paulson is in private practice at Arizona Natural Health Center and has an oncology-focused practice that brings together the best of natural therapies for cancer care. Dr Paulson enjoys sharing her naturopathic oncology passion by teaching oncology at SCNM. You can reach Heather Paulson at www.aznaturalhealth.com or [email protected].