Tolle Totum

Iva Lloyd, BScH, RPE, ND

It is common to think of chronic pain from a structural or functional perspective. What is not as common, but is equally important, is the psychological aspect of pain. The psychological aspect refers to how symptoms and conditions, such as chronic pain, impact a person’s mental and emotional state of health and how the mind can influence and, in fact, override, the intensity, duration and frequency of pain that a person experiences.

The naturopathic principle, “tolle totum” (treat the whole person) encompasses the understanding that all aspects of an individual are connected, that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The research behind pain and pain management highlights the important role that a person’s thoughts and emotions play, with respect to both the manifestation and the management of pain. Pain catastrophizing, fear-avoidance, depression, and other psychological states worsen pain and decrease treatment effectiveness. Addressing the psychological aspect of pain through mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapies, along with naturopathic therapies, is an important aspect of pain management.

Integration of the Individual

Any condition affects the entire person, not just a specific organ or system. Health and disease are a result of a complex interaction of all aspects of a person, including their life and environment. The psychological, functional, structural and spiritual (or personal essence) aspects of an individual make up an inseparable whole that is interconnected and interdependent with family, community and environment. Any pattern of chronic pain, in any aspect of a person, resonates throughout all levels of being.1

The structural aspect of an individual represents the alignment of the physical body. When structure is aligned it provides proper distribution of weight among the joints, allows the bodily fluids to flow unimpeded, and provides for harmonious cellular communication.1 Structural issues, whether caused by falls and injuries, chronic poor posture, or underlying conditions such as scoliosis, osteoporosis or arthritis, result in a corresponding impact on the other layers. With arthritis, for example, there are functional responses to structural issues, such as inflammation and pain. On the psychological level there is often a range of responses, such as frustration, irritability, anxiety, and even depression.

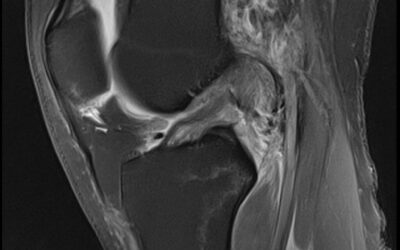

The functional aspect is the “work-horse” of the body. It relates to the immune, respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, musculoskeletal, endocrine, and nervous systems. It includes the inner organs, glands, tissues and body fluids. It encompasses how the body’s systems interact and communicate at the system, organ, and molecular levels. It involves the movement of fluid and energy between the cells, and within the cells, tissues and organs. Both the psychological and structural aspects are able to override and influence the body’s functional ability; it in turn is also able to override theirs.1 The functional aspect of an individual has historically been the primary focus of conventional medicine, as it is the most easily analyzed and studied. Tools such as laboratory testing, radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging scans, and ultrasounds give doctors an important perspective on what is happening at a cellular, organ system, and physiological level. Functional assessments reveal a person’s current state of health and the progression of disease, but they often do not correlate with a person’s mental or emotional state of health or quality of life, especially when it comes to conditions that involve chronic pain.

The psychological aspect of an individual relates to thoughts and emotions. It represents how individuals perceive themselves and the world and how they communicate with their world and with themselves. It permeates the whole person and is able to influence the functional and structural aspects of an individual. The psychological aspect is continually being shaped and influenced by experiences, the environment and a person’s state of health.1 The unconscious component holds the deep personal beliefs that influence a person’s life and that “filter” and assess the impact and significance of events. The conscious component relates to the thoughts and emotions of which a person is aware. It represents a person’s ability to perceive and to be aware of symptoms such as pain, as well as the thoughts and emotions that a person has about their symptoms. The verbal or expressive component relates to how one communicates their thoughts, emotions, sensations, and perceptions. It is affected by whether or not they feel heard and understood.1 Psychological health is greatest when the unconscious, conscious and expressive components are congruent.

In the United States, pain accounts for around 80% of physician visits and incurs an estimated annual cost of $100 billion annually, in terms of healthcare expenditures or lost productivity.2 How a person experiences pain depends very much on their psychological state, yet the current focus of pain management is primarily focused on the functional and structural aspects of pain. Including the psychological impact of pain as part of the naturopathic assessment and treatment can greatly improve the understanding, by both patient and practitioner, of the impact and significance of pain for each patient, and can greatly assist in determining the most effective treatment strategy.

Pain Catastrophizing

Pain catastrophizing is defined as an exaggerated negative “mental set” or a negative cognitive-affective response to anticipated or actual pain.2 It has been defined as “the tendency to magnify or exaggerate the threat value or seriousness of pain sensations,… to feel helpless in the context of pain, and [to be unable] to inhibit pain-related thoughts in anticipation of, during or following a painful encounter.” 2 In patients who are either in chronic pain or pain-free, pain catastrophizing is now considered to be a potent predictor of pain-related outcomes.2

Some research indicates that “catastrophizing might best be viewed from the perspective of hierarchical levels of analysis, where social factors and social goals may play a role in the development and maintenance of catastrophizing, whereas appraisal-related processes may point to the mechanisms that link catastrophizing to pain experience.”3

The notion that pain catastrophizing contributes to a more intense pain experience and increased emotional distress has been supported by research for a number of years. It is positively linked with increased levels of depression and anxiety and inversely linked with positive mental traits such as optimism and hope.4,5 Feelings of helplessness, rumination and magnification have also been found to positively correlate with pain catastrophizing .2 Magnification involves wondering whether something serious may happen, such as the pain getting worse; rumination occurs when a person cannot stop thinking about their pain; and helplessness refers to the feeling of not being able to go on, or feeling that nothing can be done to lessen the pain.2

Pre-surgery anxiety is one form of pain catastrophizing. Chronic post-operative pain is positively linked with pre-surgery anxiety. One study found this to be most relevant for musculoskeletal surgeries, where a 67% correlation was found, versus 36% for other types of surgeries .5 Pain catastrophizing was found to be more predictive of chronic post-operative pain, compared with general anxiety or specific pain-related anxiety. Other studies have found that strong relationships exist between fear of pain, catastrophizing, and anxiety, but also that the intensity of pain is most closely linked to pain catastrophizing.6 Pain catastrophizing has also been associated with decreased response to pharmacological interventions, as shown in a 3-week study of 82 patients with neuropathic pain.7

Psychological Factors

It is generally accepted that chronic pain reduces quality of life, including mood and physical and social functioning. Depression, fear of pain, and anxiety are psychological traits known to worsen pain symptoms and to impede treatments focused on pain resolution or management. Conversely, optimism, hope, and self-efficacy traits are protective, resulting in decreased pain perception and impact.4 Other factors that often decrease pain parameters include pain coping strategies and a positive social support system.

The positive association between pain and depression in the general population has been well established, with the degree of depression strongly correlating with the severity of pain.8 Depression is often linked with pain catastrophizing, anxiety, and other negative psychological states. One study showed that low back pain symptoms tended to last longer and be more intense when a person was in a depressed state prior to the incident that caused the pain.9 Another study of 480 participants with chronic temporomandibular muscle and joint disorders (TMJD) found that the progression of chronic TMJD pain and the degree of disability was positively related to pain catastrophizing and depression.10

Even in children and adolescents, pain is often linked with depression. In a study with 400 patients, ages 8 to 17 years, with chronic abdominal pain, depression was correlated with the presence of abdominal pain, especially when 3 or more non-gastrointestinal symptoms were also present.11 In the elderly, pain and depression are both common and are associated with age-related cognitive decline.12 What remains to be clarified by research is whether depression is initially caused by pain, or whether depression causes increased pain.8

Fear of pain and anxiety, especially when extreme, may be considered “yellow flags” when it comes to the onset of pain, especially musculoskeletal pain. These “yellow flags” are factors that can worsen pain and negatively impact treatments. Addressing psychological “yellow flags” can significantly improve treatment outcomes.13 In a study of 19 males and 23 females with “no history of neck or shoulder pain, no sensory or motor impairments of the upper-extremity, who were not regularly participating in upper-extremity weight training, were not currently or regularly taking pain medication, and who had no history of upper-extremity surgery,” it was found that fear of pain was the primary factor that accounted for induced delayed-onset muscle soreness of the shoulder.14 Fear of pain appeared to be more significant than anxiety or pain catastrophizing.

The “fear-avoidance model” looks at chronic pain as a vicious circle that begins with pain catastrophizing; this leads to fear of pain, which in turn leads to avoidance, and finally to chronic pain, depression, and increased suffering.15 Fear of movement, known as kinesiophobia, has emerged as a significant predictor of pain-related outcomes including disability and psychological distress across various types of pain (eg, back pain, headache, fibromyalgia, and complex regional pain syndrome). One study of 88 men and 173 women with chronic musculoskeletal pain found that kinesiophobia was higher in men (72%) than women (48%).16 Women with a high degree of kinesiophobia tended to be younger and were more affected, as evidenced by increased tiredness, stress, and greater overall interference and dissatisfaction with life. Kinesiophobia, in general, was not related to age, the duration of pain, or depression/anxiety.

Psychological Therapies

There are many naturopathic therapies, such as nutraceuticals, herbs, and homeopathics that are known to effectively address psychological conditions such as depression and anxiety. It is the author’s opinion that when the psychological aspect plays a significant role in any condition, it is beneficial to address it directly with naturopathic counseling, mindfulness exercises, or by simply listening attentively to the patient’s story. Mindfulness-based stress reduction exercises (MBSR) and cognitive behavioral interventions have been proven to effectively decrease pain by reducing catastrophizing, fear and avoidance.17 Other effective strategies include distraction, reinterpretation, acceptance, and exercise and task persistence.

Mindfulness exercises such as meditation, relaxation, general yoga, body scanning, and positive thought reinforcement are known to improve pain parameters and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measurements, yet the effectiveness varies with the type of pain and subject compliance with the MBSR exercises.18 A longitudinal investigation of 133 chronic pain patients was completed using the Short-Form 36 Health Survey and Symptom Checklist-90-Revised.18 What was discovered was that patients with arthritis, back/neck pain, or 2 or more comorbid pain conditions demonstrated a significant change in pain intensity and functional limitations following MBSR exercises. Those with arthritis tend to show the greatest degree of improvement, whereas those with chronic headache or migraines experienced the smallest improvement in pain and HRQoL. Patients with fibromyalgia had the smallest improvement in psychological distress.

MBSR exercises have not always found to be effective in short-term studies (8 weeks or less). In a study of 63 patients with rheumatoid arthritis who either served as controls or received 8 weeks of MBSR followed by a 4-month program of continual reinforcement, it was found that although differences between the MBSR group and controls were not statistically significant at 8 weeks, at 6 months the treated subjects showed a significant improvement in psychological distress and well-being, as well as marginally significant improvement in mindfulness and depressive symptoms.19

In an 8-week study involving 50 subjects that compared the effectiveness of MBSR versus cognitive-behavioral stress reduction (CBSR), it was found that those in the MBSR group had significant improvements on all parameters measured – “perceived stress, depression, psychological well-being, neuroticism, binge eating, energy, pain, and mindfulness.”20 CBSR subjects improved on 6 of 8 outcomes, with significant improvements observed only in the areas of well-being, perceived stress, and depression.

A 2012 Cochrane review of 37 studies,21 involving 1938 participants, evaluated the effectiveness of psychological therapies— principally cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural therapy— for reducing pain, disability, and improving mood in children and adolescents with recurrent, episodic or persistent pain, especially pain associated with headaches. Analyses revealed that pain had improved in the headache and non-headache groups at post-treatment, and in the headache group at follow-up. Disability significantly improved in the non-headache group at post-treatment. The authors concluded that “psychological treatments are effective in reducing pain intensity for children and adolescents (<18 years) with headache, and benefits from therapy appear to be maintained.”

Conclusion

The correlation between chronic pain and psychological conditions such as depression and anxiety is well established. The ability of pain catastrophizing and fear-avoidance to worsen pain and to inhibit the effectiveness of treatment has also been extensively studied and proven. Studies stress the importance of addressing all aspects of a person in chronic pain, that is, the need to include the psychological and psychosocial state of a person, not just the functional or structural. Mindfulness-based stress reduction exercises or cognitive behavioral therapy can greatly increase the effectiveness of any treatment plan for chronic pain.

Dr. Iva Lloyd founded Naturopathic Foundations Health Clinic in 2002 after graduating from the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM). Her focus is on identifying the factors contributing to disease and understanding their physiological and energetic patterns. She is known for her patience, knowledge and ability to guide patients through a life transformation.

Dr. Iva Lloyd founded Naturopathic Foundations Health Clinic in 2002 after graduating from the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM). Her focus is on identifying the factors contributing to disease and understanding their physiological and energetic patterns. She is known for her patience, knowledge and ability to guide patients through a life transformation.

She has studied many different healing systems. Dr. Lloyd is a Registered Polarity Therapist and Educator and a Reiki Master.

She is editor of the professional journal of the CAND, and she is on the editorial board of other professional journals. She teaches part-time at the CCNM and she presents internationally on naturopathic assessments, the energetics of health and the role of the mind in healing.

References

- Lloyd I. (2009) The Energetics of Health: A Naturopathic Assessment. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

- Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(5):745-758.

- Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(1):52-64.

- Pulvers K, Hood A. The role of positive traits and pain catastrophizing in pain perception. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17(5):330.

- Theunissen M, Peters ML, Bruce J, et al. Preoperative anxiety and catastrophizing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with chronic postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(9):819-841.

- Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Rodgers W, Ward LC. Path model of psychological antecedents to pain experience: experimental and clinical findings. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(3):164-173.

- Mankovsky T, Lynch ME, Clark AJ, et al. Pain catastrophizing predicts poor response to topical analgesics in patients with neuropathic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2012;17(1):10-14.

- Haythornthwaite JA, Benrund-Larson LM. Psychological aspects of neuropathic pain. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(2 Suppl):S101-S105.

- Elfering A, Käser A. Melloh M. Relationship between depressive symptoms and acute low back pain at first medical consultation, three and six week of primary care. Psychol Health Med. 2013 Mar 20. [Epub ahead of print]

- Velly AM, Look JO, Carlson C, et al. The effect of catastrophizing and depression on chronic pain–a prospective cohort study of temporomandibular muscle and joint pain disorders. Pain. 2011;152(10):2377-2383.

- Little CA, Williams SE, Puzanovova M, et al. Multiple somatic symptoms linked to positive screen for depression in pediatric patients with chronic abdominal pain. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(1):58-62.

- Kruger TM, Abner EL, Mendiondo M, et al. Differential reports of pain and depression differentiate mild cognitive impairment from cognitively intact elderly patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(2):107-112.

- Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, Main CJ. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (“yellow flags”) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):737-753.

- George SZ, Dover GC, Fillingim RB. Fear of pain influences outcomes after exercise-induced delayed onset muscle soreness at the shoulder. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(1):76-84.

- Crombez G, Eccleston C, Van Damme S, et al. Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(6):475-483.

- Bränström H, Fahlström M. Kinesiophobia in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: differences between men and women. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(5):375-380.

- Schütze R, Rees C, Preece M, Schütze M. Low mindfulness predicts pain catastrophizing in a fear-avoidance model of chronic pain. Pain. 2010;148(1):120-127.

- Rosenzweig S, Greeson JM, Reibel DK, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain conditions: variation in treatment outcomes and role of home meditation practice. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68(1):29-36.

- Pradhan EK, Baumgarten M, Langenberg P, et al. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(7):1134-1142.

- Smith BW, Shelley BM, Dalen J, et al. A pilot study comparing the effects of mindfulness-based and cognitive-behavioral stress reduction. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(3):251-258.

- Eccleston C, Palermo TM, de C Williams AC, et al. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003968.