Accreditation Nation

FRASER SMITH, MATD, ND

Naturopathic medical education is a recognized higher-education enterprise that meets the same standards as first-professional doctorate (MD, DO, DC, OD, etc) training. This is true of naturopathic training in both the United States and Canada. We can stand by and stand on our “ND” credential and be proud of it. Those of us who have been through it know in our bone marrow that it’s at least as demanding as any such doctorate.

But it was not always this way. Naturopathic medical education was initially positioned outside of the higher-education world. It had to be this way, and in its time, independent medical colleges were very common. This proved to be a factor in the decline and near extinction of the profession in the mid-20th century. The regrouping and resurgence of our medical education is nothing short of a triumph.

This month, we’ll look at how accreditation functions at different levels. This important factor has a large magnitude effect on our system of education; however, accreditation is not as prescriptive and determinative as one might think.

United States & Canada: How It Works

According to the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA),1 “‘Accreditation’ is review of the quality of higher education institutions and programs.” This council is an advisory body to the United States Department of Education (USDE). One of the functions of CHEA is to recognize various accreditation agencies. Those agencies are the ones that directly evaluate schools. Although it may seem unnecessarily bureaucratic to have a sort of accreditor for the accreditation agencies, there are solid reasons for it, which we’ll discuss further on.

In Canada, the preferred term is “quality assurance,” and this process is largely carried out by the provinces. For example, Ontario and British Columbia both have provincial government agencies that work with the universities and colleges of their province to ensure quality. If you wanted to open a new degree-granting institution in Ontario, you would have to obtain a number of permissions as well as submit an application to the Post-secondary Education Quality Assurance Board (PEQAB).2 If you have a program that undergoes a quality assurance process in Ontario, you will be reviewed by a board that is accountable (though maybe at arm’s length) to the Ministry of Training, Colleges, and University.3 In British Columbia, you’ll seek consent from the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training to offer your degree.4 There are many more facets to this, including the fact that, for some time now, the Canadian universities have had their own association and share best practices.

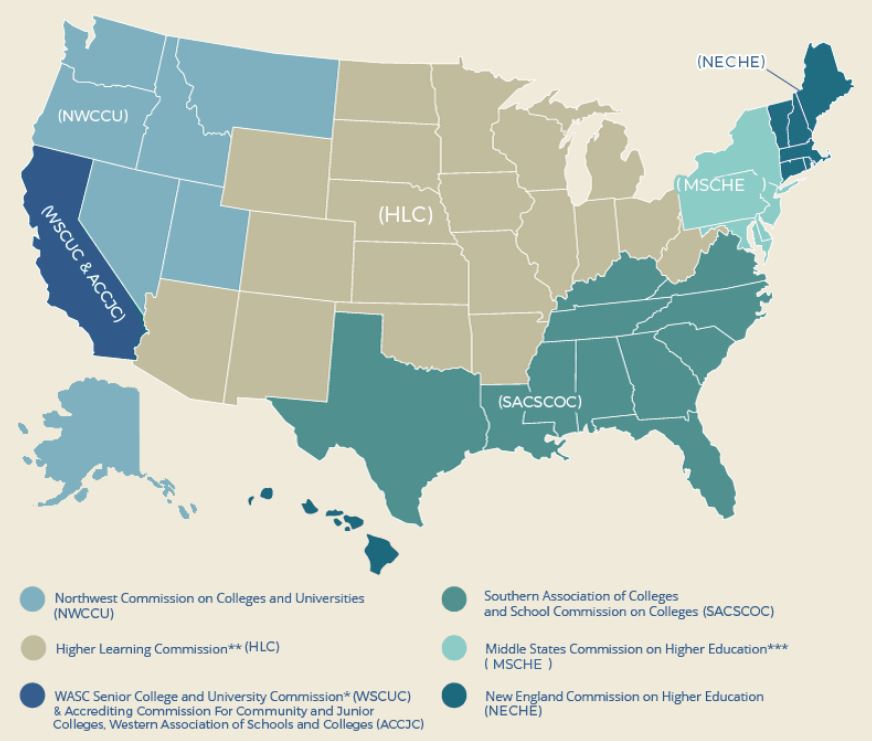

In the United States, there are regional accreditors that provide quality assurance for universities and colleges by geographic region. These accreditors are recognized by the United States Department of Education, which includes a recommendation by the CHEA (the “accreditor of the accreditors”), mentioned above.

The “regionals” in the United States include the following5:

- New England Commission on Higher Education (NECHE)

- Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE)

- Southern Association of Colleges and Southern Commission of Colleges (SACSCOC)

- Higher Learning Commission (HLC)

- Western Association of Schools and Colleges’(WASC) Senior College and University Commission (WSCUC)

- Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities (NWCCU)

Figure 1. US Accreditation Regions

How Accreditation Evolved

The Higher Learning Commission comprises a vast stretch of the United States – a parallelogram-shaped cluster of states from West Virginia to Wyoming, down to Arizona, and across to Arkansas. Until very recently, regional accreditors could deal only with states in these geographic areas. For example, MSCHE would work with schools in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. Recently, a rule was passed by USDE6 that allows institutions to choose their accreditor. There has been no rush to do so, as to move one’s accreditation is a big undertaking and the benefits may not be clear.

In Canada, higher education, along with degree granting, was exclusive to what was termed “land grant” institutions for many years. A few private institutions, mostly seminaries (religious training institutions), were the exception. In the new millennium, this changed. Provinces began to open the door to private institutions seeking degree status. Community colleges were also able to pursue a pathway to offering degrees for some programs, in addition to their tradition diplomas. Canada, land-grant institutions, new avenues. Growth. Innovation. Good for naturopathic medicine. This pathway paved the way for great accomplishments by our colleges in Canada. What had been a rather exclusive, and certainly high-quality club, began to broaden. As the scholar of higher education, Donald N. Baker, noted in his 2010 article,7 calls for more accountability in the effective use of government funding for higher education led to audits of the university system.

When Canada signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), US institutions of higher education could now operate in Canada, which in theory allowed some diversification of higher education. Although the progression to degree-granting status for any school has been conducted with both care and rigor, it was a development of great significance for naturopathic medicine. An institution such as the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM), while not a publicly funded University, grants a degree (ND). This is no small feat, and the leadership of Dr Bob Bernhardt, the current president of CCNM, and the incredible work of his team led this to fruition. The process was kicked off by his predecessor, Dr David Schleich, which gives some insight into the time and work involved.

Evaluation & Peer Review

In either country, the types of issues with which accreditation concerns itself are similar. Is governance (the Board of Trustees who hire a president and approve a budget) stable and capable? Is the administration operating effectively? Is it hiring and retaining qualified personnel? Is the institution financially sound? Is the education delivered by a qualified group of faculty, and are they using effective methods? Does the institution have methods for evaluating its own success in meetings its goals (institutional assessment)? Are all of the features of a functioning higher-education institution in place, eg, a safe campus, high functional technology, student support services etc?

The nature of this process has some common denominators too. There is a large emphasis on peer review. That is, the team that comes to visit and conduct an evaluation of a school has experience in, and is usually working at, a similar institution. Those who review the submissions are also from the higher-education world. This can be offset a bit by members of the public with other backgrounds. The principle involved is that of “peer review”; ie, this accreditation process is heavily dependent on education professionals working with education professions. Likewise, the institutions under review provide input into the evaluation, including from administration, faculty, staff, and students.

CNME & Programmatic Accreditation

Regional or provincial accreditation is just 1 part of the story, however. Naturopathic medicine programs have what is called a specialty, or “programmatic,” accreditor, namely the Council on Naturopathic Medical Education (CNME).8 The Articles of Incorporation of the CNME were signed on August 13, 1978. The signatories were Dr Ronald R. Hoye, Sr, Stanley D. Crow, Dr Lucien John B. Cardinal, and Dr John Bastyr. The initial Board of Directors included Dr Joseph Pizzorno and Dr Jeffery Bland.

This was a momentous event. A modern, licensable, medical profession must have a programmatic accreditor for its institutions. Chiropractic medicine was at this junction, and the Council on Chiropractic Medicine was founded in 1971.9 The MD programs are recognized by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Osteopathic medicine has its own, and so on. This had historical, contemporary, and future-facing importance.

Historically, a weakness of the naturopathic medicine education was a lack of accreditation. In fact, we can’t really call it a “system,” although we could say it’s a family or network of programs. Some were ensconced in chiropractic colleges, such as the one at National Chiropractic College (now NUHS), which offered an ND degree from the mid-1920s until 1952 (and again from 2006, on). Others were small, stand-alone colleges. They might have included some great teaching, but they were not built to last for the world that was taking shape in the early-to-mid-20th century. Accreditation encourages innovation and quality, and there is a reason that all health professions now do it. Not having it was normal enough for 1895 when Benedict and Louisa Lust and colleagues opened the first naturopathy school. But by the time of the Flexner Report and, really, a societal move towards quality assurance and standards of various kinds (foods, medicines, automobiles, etc), this ad hoc way of starting a school – very common in the MD world as well – had run its course.

In the milieu of the 1980s, the arrival of the CNME had another epic impact. At that time, and well into the 1990s, the correspondence school that offered “naturopath” diplomas really picked up steam. Many of these schools ended up on lists of “diploma mills.” Accreditation helped potential students discern what kind of school they wanted to attend. It helped licensing authorities determine to whom they wanted to issue licenses. When the Naturopathic Physicians Licensing Examination (NPLEX) came along, it was clear who would be eligible to apply to sit for such exams: those who attended a CNME candidate- or accredited program.

In a future-facing way, this has been a powerful factor in our arguments to state and provincial legislative assemblies. Our education is accredited by a specialty accreditor that is, itself, recognized by the USDE. Regardless of the confusion that is created by other types of natural-healing training, it is plain to anyone what an accredited naturopathic medicine degree program is. Those of us who participate in writing and proposing legislation to potential sponsors have no problem defining the educational standards, which is extremely important when crafting a bill.

As the profession has grown, so has the impact of a specialty accreditor continued to be vital. The CNME has a mechanism for reviewing the standards of residency programs as they are administered through the colleges. The CNME has standards around electronic/online learning. More ND programs came along after that day in August 1978, and having the council there to ensure that they developed according to shared standards was really important. The concept of peer review was mentioned earlier, and the peer review provided by the CNME to a new program is extremely helpful. Having personally been involved in a brand new program, I can’t imagine it developing to full stature without the CNME, even though it was established at a highly committed institution that had the resources and will to make the program work. Like a good naturopathic physician, the CNME helps the program to remove obstacles to improvement, and further sharpen its strengths.

A Key Player in Our Success

The standards of the CNME are rigorous. They include some common-feature type of issues, such as student services and finances. Of course, they emphasize academic and clinical education. In keeping with the times, the importance of program assessment (asking how you know that your program is succeeding in its mission) is a major aspect of the standards. The CNME works with schools, and although the standards are rigorous, they are applied in the light of an individual institution’s values, culture, mission, and even locale. Much like a good naturopathic physician, the CNME applies its standards in an individualizing (but fair and consistent) manner, and considers the “whole” program.

Naturopathic medical education can stand next to any first-professional educational system as a peer. And the role of accreditation, institutional and programmatic, is one of the fundamental reasons that we have been successful.

References:

- Council for Higher Education Accreditation. Accreditation & Recognition. Available at: https://www.chea.org/about-accreditation. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- Postsecondary Education Quality Assessment Board. Available at: http://www.peqab.ca/. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- Ontario. Ministry of Colleges and Universities. Available at: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ministry-colleges-universities. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- British Columbia. Ministry of Education. Available at: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/organizational-structure/ministries-organizations/ministries/advanced-education-skills-training. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- Council on Higher Education Accreditation. Regional Accrediting Organizations. Available at: https://www.chea.org/regional-accrediting-organizations-accreditor-type. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- Eaton JS. Will Regional Accreditation Go National? March 17, 2020. Inside Higher Ed. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/03/17/pros-and-cons-having-regional-accreditors-go-national-opinion. Accessed November 28, 2021.

- Baker DN, Miosi T. The Quality Assurance of Degree Education in Canada. Res Comp Int Educ. 2010;5(1):32-57. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2304/rcie.2010.5.1.32. Accessed November 28, 2021.

- Council on Naturopathic Medical Education: Accrediting naturopathic doctoral programs in the U.S. and Canada. Available at: https://cnme.org/. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- The Council on Chiropractic Education. History. Available at: https://www.cce-usa.org/history.html. Accessed December 1, 2021.

Fraser Smith, MATD, ND is Assistant Dean of Naturopathic Medicine and Professor at the National University of Health Sciences (NUHS) in Lombard, IL. Prior to working at NUHS, he served as Dean of Naturopathic Medicine at the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM) in Toronto, Ontario. Dr. Smith is a licensed naturopathic physician and graduate of CCNM.