Not Enough Milk? Preventing & Managing Low Breast Milk Supply

EILEEN PARK, IBCLC, ND

Breastfeeding is a biological norm, and the risks of not breastfeeding are well known by the public and well accepted

in medicine. As a result, a recent national survey showed that over 90% of mothers in Canada initiate breastfeeding.1 However, the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months was only 13.8%. A separate study demonstrated that one of the leading causes for this high drop-off rate is low milk supply, or the perception of having “not enough milk.”2

Causes of Low Breast Milk Supply

Breast milk supply can be compromised by numerous biopsychosocial factors, many of which are associated with delayed onset of milk production within the first few days.3 Lactogenesis – the process of milk production – begins in pregnancy and continues after birth. Lactogenesis II can only begin once the placenta has been delivered. Many factors, including mode of delivery,4 maternal diabetes,5 and maternal and infant illness or emotional stress,6 may lead to delayed lactogenesis II, which may translate to delayed onset of milk production and result in insufficient milk volume.6 During lactogenesis III, milk supply is maintained by the continual removal of breast milk, which is dependent on baby’s needs.7 Therefore, proper management of feedings is crucial to maintain an optimal milk supply. Factors that can lead to mismanagement of feedings include scheduled feedings, poor latching technique, use of breast milk substitutes, and introduction of artificial nipples.

Other causes of decreased milk supply can include a history of breast surgery and use of medications (eg, birth control or antihistamines). Though the evidence is lacking, maternal health problems (eg, anemia or hormonal imbalances) may also have an effect. From an Asian medicine perspective, “breast milk not flowing” may be due to Qi and/or Blood Deficiency, perhaps caused by a difficult delivery or profuse blood loss during birth, or Liver Qi Stagnation due to worry, frustration, or shame.8

Preventing & Managing Low Breast Milk Supply

Preventative measures should start with prenatal care and education. Again, there is no direct evidence for the effects of prenatal health on breast milk supply; however, it is prudent to ensure optimal nutrition, balanced hormones (eg, thyroid, adrenal), and mental/emotional health. Moreover, prenatal education about breastfeeding allows for goal-setting, as well as fostering healthy expectations and confidence in the fact that breastfeeding is a biological norm.9 Since mode of delivery can affect milk supply,4 education about natural birthing and minimizing interventions when possible should be included. After delivery, babies should be given unlimited access to the breast. This can be done through skin-to-skin contact around the clock as much as possible, and by identifying early feeding cues in the baby, which allows for effective feedings according to baby’s needs.10 This will allow the mother’s milk supply to adjust to the baby’s needs.

Early assessment of infant oral anatomy, to check for abnormalities such as ankyloglossia (also known as tongue-tie) is critical, as such abnormalities may interfere with breast milk removal and result in decreased supply.11

Latch & Breast Milk Flow

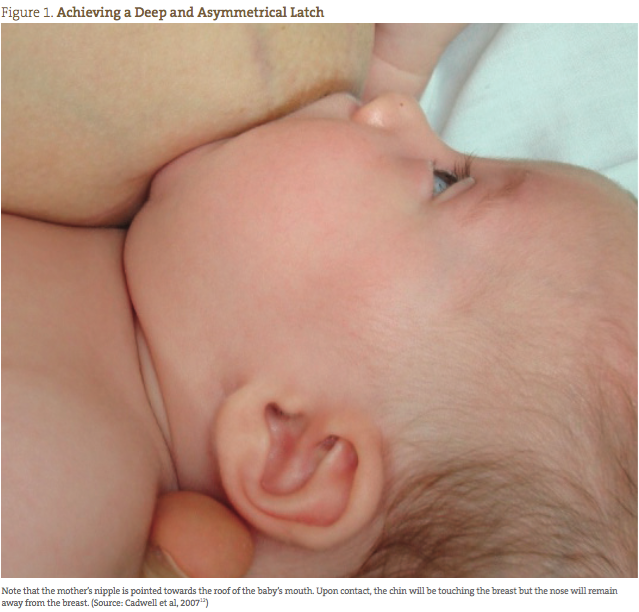

The most important factor influencing breast milk supply is most likely the latch. A latch that allows for optimal milk transfer is one that is deep and asymmetrical where the chin is touching the breast, but the nose is away from the breast (Figure 1).12 It is also essential to know if the baby is actually transferring milk from the breast. Many assume that a baby is getting milk every time it sucks at the breast. As a result, there is much emphasis on the timing of feedings; we assume that a longer feeding equals increased milk intake. However, this is not necessarily the case, as there is a difference between sucking without milk transfer and drinking with milk transfer. Sucking without milk transfer involves rapid up- and-down movements of the chin, whereas drinking involves a longer drawing action of the chin. Recognizing this difference is the way to know if a baby is getting enough and if the mother’s milk supply is sufficient. It also allows the mother to take action when the baby is not drinking well, by switching sides or using tools such as breast compressions to improve milk transfer and thereby maintain supply. (Visit www.nbci.ca for videos that demonstrate the difference between sucking versus drinking and to learn how to use breast compressions).

Herbs & Acupuncture

If the baby is still not getting enough breast milk using the above measures, treatments including galactagogues and acupuncture may be helpful. Just like any other condition, there is no 1 magic bullet that will provide a quick fix. As always,

it is important to rule out any underlying issues, such as hormonal imbalances or nutrient deficiencies, and to treat the root cause. Commonly used herbs include fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum), blessed thistle (Cnicus benedictus), goat’s rue (Galega officinalis), alfalfa (Medicago sativa), nettles (Urtica dioica), and shatavari (Asparagus racemosus). Fenugreek and blessed thistle are most commonly used and accessible in Canada. Goat’s rue can be especially useful if there is a history of insulin resistance (eg, gestational diabetes), as it contains the same active constituent as the medication metformin, and nettles are appropriate if there is a history of excessive bleeding or iron deficiency.13 There are very few studies on the efficacy of these commonly used herbal galactagogues, and those that exist involve animals or small sample sizes. Domperidone – a D2 dopamine antagonist – is a commonly used pharmaceutical galactagogue that has been found to be effective and safe in healthy mothers.14

Acupuncture points that influence breast milk production include CB17, GB21, SI1, and ST12. Based on the patient’s underlying constitution, additional points may be added.8 For example, add LV8 and ST36 for nourishing blood, or LV3 and GB34 for moving Qi stagnation.

Treatments – whether herbal, pharmaceutical, or acupuncture – will be less effective unless the feedings are well managed. Reasons for low milk supply may be multifactorial and sometimes can be quite complicated to treat; however, in most cases, proper prevention and management are sufficient to ensure optimal breast milk supply.

Eileen Park, IBCLC, ND, graduated from the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2012. She is a board-certified doctor of naturopathic medicine practicing in Ontario. Her special interests include, but are not limited to, women’s health, hormone disorders, fertility, prenatal and postpartum support, and pediatric care. Eileen is also an international board-certified lactation consultant (IBCLC) and is currently an executive director and faculty member at the International Breastfeeding Centre in Toronto. Eileen has also received CAPPA-approved labor doula training.

Eileen Park, IBCLC, ND, graduated from the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2012. She is a board-certified doctor of naturopathic medicine practicing in Ontario. Her special interests include, but are not limited to, women’s health, hormone disorders, fertility, prenatal and postpartum support, and pediatric care. Eileen is also an international board-certified lactation consultant (IBCLC) and is currently an executive director and faculty member at the International Breastfeeding Centre in Toronto. Eileen has also received CAPPA-approved labor doula training.

References

Al-Sahab B, Lanes A, Feldman M, Tamim H. Prevalence and predictors of 6-month exclusive breastfeeding among Canadian women: a national survey. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:20.

Li R, Fein SB, Chen J, Grummer-Strawn LM. Why mothers stop breastfeeding: mothers’ self-reported reasons for stopping during the first year. Pediatrics. 2008;122 Suppl 2:S69-S76.

Brownell E, Howard CR, Lawrence RA, Dozier AM. Delayed onset lactogenesis II predict the cessation of any or exclusive breastfeeding. J Pediatr. 2012;161(4):608-614.

Chapman DJ, Young S, Ferris AM, Pérez-Escamilla R. Impact of breast pumping on lactogenesis stage II after cesarean delivery: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):E94.

Matias SL, Dewey KG, Quesenberry CP Jr, Gunderson EP. Maternal prepregnancy obesity and insulin treatment during pregnancy are independently associated with delayed lactogenesis in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(1):115-121.

Dewey KG. Maternal and fetal stress are associated with impaired lactogenesis in humans. J Nutr. 2001;131(11):3012S-3015S.

Cregan MD, Hartmann PE. Computerized breast measurement from conception to weaning: clinical implications. J Hum Lact. 1999;15(2):89-96.

Maciocia G. Obstetrics and Gynecology in Chinese Medicine. 2nd edition. London, England: Churchill Livingstone;2011.

Noel-Weiss J, Rupp A, Cragg B, et al. Randomized controlled trial to determine effects of prenatal breastfeeding workshop on maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy and breastfeeding duration. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(5):616-624.

Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N, Dowswell T. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD003519.

Garbin CP, Sakalidis VS, Chadwick LM, et al. Evidence of improved milk intake after frenotomy: a case report. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1413-e1417.

Cadwell K. Latching-on and suckling of the healthy term neonate: breastfeeding assessment. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52(6):638-642.

West D, Marasco L. The Breastfeeding Mother’s Guide to Making More Milk. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2008.

Osadchy A, Moretti ME, Koren G. Effect of domperidone on insufficient lactation in puerperal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:642893.