Neuropathy & Long-term PPI Use: A Case Study

Jennifer Brusewitz, ND

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common condition, reported to occur in up to 22% of the US population; it is frequently treated with over-the-counter (OTC) proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs).1 The class of PPIs include omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole, and esomeprazole. The mechanism of action of these drugs involves blocking the enzyme H-K-ATPase in the gastric parietal cells, thereby suppressing hydrochloric acid (HCl) production and reducing the irritation and mucosal damage caused by errant HCl in the esophagus.

Long-term use of PPIs (defined as utilizing a prescription of 120 or more tablets of any PPI within the past year, ie, taking 1 tablet daily for at least 4 months) is prevalent in 2.1% of the general population.2 The FDA has advised that no more than three 14-day treatment courses of any PPI should be used in 1 year, though the incidence of long-term treatment is widespread and has inadvertent consequences, including nutrient deficiencies, as demonstrated in the following case study.3

Case Study

An energetic 72-year-old male presented to our clinic with a several-year history of peripheral neuropathy in his hands and feet. Constant in its presentation, the patient described the neuropathy as a tingling and numbness extending into the digits of his hands and feet bilaterally. Occasionally, the sensation became painful in the first 3 digits of his left foot. He described the onset as being several years prior, though could not recall exactly when the sensation started. The patient reported daily use of self-prescribed omeprazole to treat heartburn symptoms for the previous 2 years. His heartburn was exacerbated if he overate, but he took the omeprazole daily, with or without overt symptoms. Additionally, the patient described himself as a heavy alcohol drinker, ingesting 2-3 glasses of beer or whiskey daily for the past 15 years.

The Role of Vitamin B12

B12-induced peripheral neuropathy has been well documented in the literature. This neuropathy results from the symmetrical degeneration of the dorsal and lateral spinal column, due to a defect in myelin formation. Patients with B12 deficiency may present with neurological symptoms, such as memory loss, irritability, dementia, weakness, sensory ataxia, and paresthesias. These paresthesias can include strange sensations, numbness, or tingling in the hands, legs, or feet. Definitive diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy is based on neuropathic symptoms, neurologic signs (decreased or absent ankle reflexes, decreased distal sensation, distal muscle weakness or atrophy), and nerve conduction study findings.4

B12 is a complex, water-soluble vitamin found primarily in meat and dairy products, necessary for many critical biological functions in the body. The process by which B12 is absorbed by the body is a journey that depends upon optimal functioning of many enzymes and multiple organs, including the stomach, pancreas, and small intestine. B12 is liberated from food under acidic conditions, in the presence of HCl and gastric protease in the stomach. It is temporarily protected from degradation by gastric juices by binding to proteins called R factors until it reaches the duodenum, the beginning of the small intestine. Once there, B12 is cleaved from R factors by pancreatic enzymes and then bound to intrinsic factor for travel further down the small intestine, to be absorbed by receptors on the enterocytes of the distal ileum.

PPIs increase gastric pH, thereby making it difficult for B12 to be liberated from dietary proteins and subsequently absorbed by the body.5 The explicit link between chronic PPI-induced B12 deficiency and subsequent peripheral neuropathy is one that has been getting greater attention in recent years. In a recent study published in JAMA, the link between PPI use and B12 deficiency was effectively laid out: patients who took PPIs for more than 2 years were significantly more likely to have a vitamin B12 deficiency, and higher doses of PPIs were more strongly associated with the deficiency.6

Diagnosis of B12 deficiency is evaluated via a complete blood count (CBC) with a peripheral smear, serum B12, homocysteine levels, and methylmalonate levels. Vitamin B12 functions as a cofactor for methionine synthase, the enzyme that converts homocysteine into methionine; therefore, if homocysteine levels are high, we might be looking at a B12 deficiency. B12 is also a cofactor for L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, which converts L-methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl CoA. In B12 deficiency, L-methylmalonyl-CoA converts instead to methylmalonic acid. Therefore, high methylmalonate levels can be another indicator of low B12 levels. Methionine is required for the formation of S-adenosylmethionine, which is critical for DNA synthesis. When DNA synthesis is impaired, the cell cycle cannot progress to the mitosis stage, thus leads to continuing cell growth without division; this presents as macrocytosis. It is important to note, however, that a CBC will not always show macrocytosis in the form of increased mean corpuscular volume (MCV) values (>100 fL). Peripheral smears can be useful for visualizing megaloblastic red blood cells and hyper-segmented neutrophils, but these findings are also not always present.

Treatment

Supplementation with vitamin B12 has been shown to alleviate neuropathic symptoms. In a report published in the Journal of Neural Plasticity, an activated form of B12 was shown to improve nerve conduction, promote the regeneration of injured nerves, and inhibit ectopic spontaneous discharges of injured primary sensory neurons.7

Treatment prescribed at the first visit of this particular case included supplementation with a B-complex containing vitamin B6, folic acid, and B12 (as methylcobalamin), in addition to vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, biotin, choline, and inositol. The patient was counseled to take 2 capsules every morning with breakfast, and asked to reduce substances in his diet known to exacerbate reflux symptoms, including coffee and alcohol (also a known risk factor for B12 deficiency, via the development of atrophic gastritis8). The patient was counseled to keep a food diary and to note any additional foods that increased his gastric reflux.

Follow-up

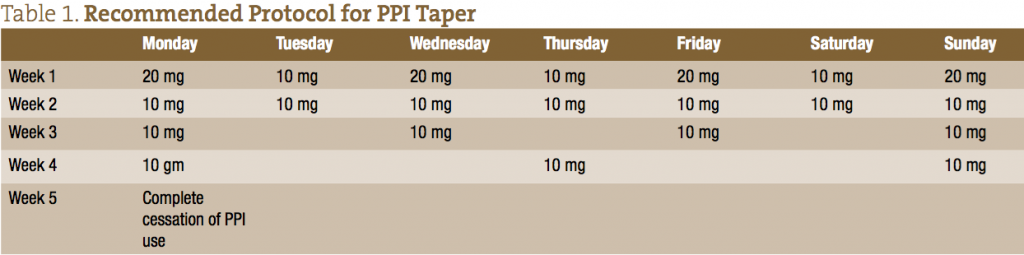

The first follow-up visit was 2 weeks later, at which time the patient reported a complete resolution of peripheral neurological symptoms. He had also stopped all alcohol use. At this second visit, the patient was given a protocol for a PPI taper, recommended to help avoid rebound acid hypersecretion, a condition that can occur when patients withdraw PPI use after treatment lasting longer than 4-8 weeks.9,10 This protocol assumes the initial daily dose of 20 mg omeprazole, and can be adjusted to whatever dose a patient is currently taking (see Table 1).

After the taper was complete, the patient’s gastric pH normalized, to allow for proper digestion of B12 from his diet. At that point, supplementation of the B-complex was discontinued.

Closing Comments

PPIs are still prescribed as the first-line standard of care for patients with GERD symptoms. According to the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines for GERD management, dietary modifications for GERD are not considered appropriate because, to date, no large-scale studies have been performed linking common food triggers and GERD.11 Despite this, ACG lists the following foods as potential triggers that should be further studied: caffeine, chocolate, spicy foods, foods with high fat content, carbonated beverages, and peppermint. Anecdotal and clinical experience heavily supports these recommendations, and provides symptomatic relief in most cases of GERD.

Education regarding the risks associated with long-term PPI use is needed, to reverse the health consequences of these easily obtained OTC drugs. Research continues to uncover the serious outcomes associated with long-term PPI use, including iron deficiency, calcium malabsorption, and disruption of gut microflora.12-14 Counseling patients on dietary risk factors for reflux, the appropriate PPI taper, and vitamin supplementation are of critical importance in the treatment of patients on PPIs experiencing peripheral neuropathy and other symptomology related to vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

Acknowledgement for the thoughtful care of our patient and hearty contribution to this case study goes to Mark Iwanicki, ND candidate at NCNM.

Jennifer Brusewitz, ND, is a 2000 graduate of the National College of Naturopathic Medicine (NCNM). She currently practices in Portland, Oregon, is a clinical supervisor at NCNM’s teaching clinics, and an instructor in the Masters of Science in Nutrition program at the Helfgott Institute. She also investigates, develops, and implements Quality Assurance standards in the NCNM Medicinary.

Jennifer Brusewitz, ND, is a 2000 graduate of the National College of Naturopathic Medicine (NCNM). She currently practices in Portland, Oregon, is a clinical supervisor at NCNM’s teaching clinics, and an instructor in the Masters of Science in Nutrition program at the Helfgott Institute. She also investigates, develops, and implements Quality Assurance standards in the NCNM Medicinary.

References

Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(6):543-552.

Reimer C, Bytzer P. Clinical trial: long-term use of proton pump inhibitors in primary care patients – a cross sectional analysis of 901 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(7):725-732.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Possible increased risk of fractures of the hip, wrist, and spine with the use of proton pump inhibitors. FDA Web site. http://tinyurl.com/263yogk. Accessed September 14, 2015.

Hemmer B, Glocker FX, Schumacher M, et al. Subacute combined degeneration: clinical, electrophysiological, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65(6):822-827.

Saltzman JR, Kemp JA, Golner BB, et al. Effect of hypochlorhydria due to omeprazole treatment or atrophic gastritis on protein-bound vitamin B12 absorption. J Am Coll Nutr. 1994;13(6):584-591.

Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2435-2442.

Zhang M, Han W, Hu S, Xu H. Methylcobalamin: a potential vitamin of pain killer. Neural Plast. 2013;2013:424651.

Bujanda L. The effects of alcohol consumption upon the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(12):3374-3382.

Gillen D, Wirz AA, Ardill JE, McColl KE. Rebound hypersecretion after omeprazole and its relation to on-treatment acid suppression and Helicobacter pylori status. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(2):239-247.

Waldum HL, Arnestad JS, Brenna E, et al. Marked increase in gastric acid secretory capacity after omeprazole treatment. Gut. 1996;39(5):649-653.

DeVault KR, Castell DO, American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):190-200.

Sarzynski E, Puttarajappa C, Xie Y, et al. Association between proton pump inhibitor use and anemia: a retrospective cohort study. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(8):2349-2353.

Eom CS, Park SM, Myung SK, et al. Use of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of fracture: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(3):257-267.

Freedberg DE, Toussaint NC, Chen SP, et al. Proton Pump Inhibitors Alter Specific Taxa in the Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome: A Crossover Trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(4):883-885.