The COHERENT Method

Matt Marturano, ND

Tolle Totum

A Biopsychosocial Approach to Functional Digestive Disorders

Since the release of the Rome IV criteria and a series of articles in a special issue of Gastroenterology (Volume 150, Issue 6, May 2016), there has been an upsurge in interest in the diagnosis and treatment of functional digestive disorders (FGID) by the medical community in general, as well as popular culture. In the introductory article, the editors explain, “Without a structural basis to explain its clinical features, or understanding of these disorders adhere to a biopsychosocial model which is best represented for these disorders in the growing field of neurogastroenterology.1”

Functional Digestive Disorders

The general consensus regarding the pathophysiology of FGID contends that they are primarily disorders of gut-brain interaction and are characterized by the following features:

- Motility disturbance

- Visceral hypersensitivity

- Altered mucosal and immune function

- Altered gut microbiota

- Altered central nervous system processing

The COHERENT Method

On top of these physiological manifestations of FGID lays an intricate network of influences comprising the “psychosocial” nature of these conditions, which include such diverse influences as: pop culture trends, familial protocols regarding communication of digestive symptoms, comfort in visually inspecting one’s own stool, food safety and hygiene practices, and even sleep and exercise behaviors. Special subsets of patients with comorbid anxiety, depression, and/or eating disorders present an additional layer of complexity for the clinician. Finally, the presence of other, more “tangible” diagnoses, such as small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), Crohn’s disease (CD), and ulcerative colitis (UC), can often take precedence in case management, potentially resulting in overlooked treatment routes.

About 5 years ago I created a model for the management of FGID, which I call The COHERENT Method. Since then, I have continued to refine this methodology and present it to various groups. The term “COHERENT” is an acronym that can be used as a mnemonic device to help practitioners remember the method’s different components. This method is licensed under a Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0), meaning that anybody may use or develop this material for their own purposes, so long as it is simply attributed to me as the original author.

I will now give you a brief overview of The COHERENT Method. It is worth noting that The COHERENT Method is not a protocol; rather, it is better conceptualized as a set of case management objectives.

Colonize microbiota – To populate the digestive ecosystem with healthful levels of beneficial microbes

The main considerations here are sources of beneficial microbes in a patient’s diet and environment. Cultured and fermented foods constitute an easy point of entry for many patients. Probiotic supplements are an additional vector for colonization. There is also evidence suggesting that exposure to certain microbes present in natural environments can have health benefits.2

It is important to be aware that the general body of literature does not support the notion that “bigger is better” when it comes to colony-forming units (CFUs) or the number of different species administered in a probiotic supplement. Rather, the consensus favors a tiered approach to understanding the physiological effects of probiotics, which differentiates between genus-, species- and strain-specific effects.3

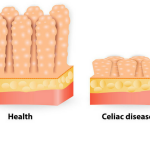

Optimize absorption – To ensure delivery of nutrients from the gut to the general circulation

Naturopathic physicians are generally well equipped to advise patients on all manner of dietary improvements. However, it has been my clinical experience that FGID patients often present already having made significant improvements to their diets, and are often perplexed that enacting these dietary changes did not result in the benefits they were expecting. It can become necessary to investigate further why a diet of predominately nutritious foods is not resulting in improved health.

This can occur for a variety of reasons, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Chronic inflammation and resulting tissue destruction, pancreatic and/or bile insufficiency, altered motility and/or osmotic gradients, and dysbiosis are all reasons why an FGID patient with an “otherwise healthy diet” might be experiencing digestive upset.

While digestive enzymes and betaine HCl can be handy, it is important to consider situations where exocrine pancreatic insufficiency or hypochlorhydria are not actually present, as this may result in symptom masking. One controlled study investigating meal-stimulated gastric acid secretion and gastric acidity in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) revealed no significant differences in pre-prandial gastric acidity between groups, although the latter group indeed demonstrated significantly increased post-prandial gastric acid secretion.4

Harmonize digestion – To support cooperation between digestive organs and feedback signals

Digestive system function is dependent upon signal coordination between several organs and tissues – including the brain – largely via the autonomic and enteric nervous systems.5 Additional pathways include the cardiometabolic, neuroendocrine, and immune systems.6 As this picture of interconnectedness unfolds, it becomes difficult to discuss the function of any other system independently of its connection to the digestive system.

Many herbal medicines have been investigated for the management of FGID,7 although only Melissa officinalis8,9 (lemon balm) and Origanum marjorana10 (marjoram) have demonstrated parasympathomimetic effects in recent research. Techniques such as abdominal breathing and mindfulness can also help patients upregulate the parasympathetic system.

Energize metabolism – To provide full-spectrum nutritional support for the body

It is common for a FGID patient presenting for an initial visit to not only already be restricting gluten and dairy but several other factors as well, such as fructose, phytates, oxalates, salicylates, and fermentable carbohydrates. These highly restrictive eating patterns are often recommended by various social networks and other practitioners, and can create additional difficulty in discerning which restrictions – if any – truly benefit the patient.

Comorbid anxiety can become generalized around food, resulting in symptoms triggered by the mere anticipation of eating. These symptoms may be misinterpreted as having resulted from the food, leading to further restrictions. In more concerning cases, restrictive eating behaviors, touted as self-management during an intake, may turn out to be an undiagnosed or undisclosed eating disorder.

Additionally, evidence suggests that the relatively low quantities of “microbiota-accessible carbohydrates” (MACs) in the standard Western diet may be a leading risk factor in the development of dysbiosis in the first place.11 For this reason, it is important to consider carefully before recommending a diet that restricts fermentable carbohydrates as a long-term treatment.

Realize self-awareness – To integrate thoughts, feelings, sensations and actions

Broadly, this objective refers to the role that mindfulness, self-awareness and, eventually, self-actualization all have in helping to cultivate an increased sense of wellness in the patient, even in the face of a potentially debilitating condition. In a more focused sense, this refers to increasing awareness regarding relationships between thought and emotional patterns and physical symptoms that are now more clearly understood to be part of the overall pathophysiology of the gut-brain-microbiota axis12 in FGID.

The full breadth of psychotherapy and mind-body techniques that are potentially helpful for FGID is well beyond the scope of this article, though it is worth mentioning that one study using cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in childhood functional abdominal pain syndrome (FAPS) (now termed centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome,13 or CAPS) found significant improvements in patients’ frequency and severity of pain episodes, missed school days, physician office visits, and PedsQL scores.14

Equalize terrain – To cleanse debris and prepare gut tissue for growth of healthy flora

The 3 main elements which come together to meet this objective of equalizing terrain are: fiber, water, and movement. Each presents its own set of benefits and challenges.

Fiber is generally already in short supply in the diet. However, because many types of fiber can increase gas and bloating in FGID patients, these individuals are especially vulnerable to fiber deficiency and their symptoms can offset the utility of fiber as a therapeutic agent. Focusing dietarily on certain subtypes of fiber can be useful. Research has shown that prebiotic gums, such as partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG), up to 6 g/day, actually improves gas and bloating.15

Encouraging patients to drink hot tea is a great intervention, for multiple reasons. The ritual of tea-making and consumption can itself be utilized as a therapy, as well as present an additional vehicle for ingesting medicinal herbs with digestive system effects, such as Mentha spp (mint), Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice), Matricaria spp (chamomile), and Foeniculum vulgare (fennel).

Finally, physical movement makes a significant contribution to the regulation of gut physiology. Taking walks or engaging in other light exercise before meals may help prime the gut neurophysiology to receive nutritional input. On the other hand, a systematic review found considerable evidence that strenuous exercise has a major (though seemingly reversible) impact on gastrointestinal integrity and function,16 raising questions about the safety and health implications of regular strenuous exercise, particularly in FGID patients and other vulnerable populations.

Neutralize invaders – To remove harmful microbes from the digestive system

Once identified, treating an infection is typically straightforward. However, certain microbiota may be potentially harmful or helpful, depending upon the circumstances and relative abundance.17 In addition to pharmacological and/or botanical antimicrobials, certain probiotic agents may be specifically indicated as adjunctive therapy. For example, Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285 has been proven safe and effective in the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea.18,19

In other situations, such as small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), first-line approaches tend to focus on berberine-containing herbs, botanical extracts, and essential oils. These have been shown to be generally equivalent to treatment with rifaximin for SIBO.20 Relatively newer methods, such as phage therapy21 and spore therapy,22 are also undergoing investigation and may warrant a closer look if more typical therapies fail.

Tranquilize gut tissue – To calm hyperactivity and manage inflammation

Managing chronic inflammation, hypermotility, and visceral hypersensitivity forms the basis of this final objective. One common link between these 3 aspects of gut dysfunction is provided by the endocannabinoid system,23,24 suggesting a need for further investigation into cannabinoid therapies, particularly cannabidiol (CBD).

Boswellia serrata and Curcuma longa have received positive reviews in the literature for treatment of chronic gut inflammation.25 Eschscholzia californica presents an interesting – albeit unstudied – option for patients suffering from centrally-mediated hypermotility and hypersensitivity.

Conclusion

Functional gastrointestinal disorders comprise an active area of research, largely fueled by technological advances permitting investigation of the human gut microbiome at the molecular level. According to the Rome IV consortium, FGID are disorders of gut-brain interaction, and a biopsychosocial approach to patient care – philosophically akin to the naturopathic principles – is now considered the standard of care for these disorders. What is more, research into several natural therapeutic agents has produced a growing body of Level I and II evidence that is worthy of consideration by any practitioner treating FGID, especially with a relative dearth of effective drug therapies.

The COHERENT Method is an open-source framework for management of FGID. Eight broad treatment objectives offer a general structure for formulation of individualized treatment plans that incorporate diet and natural therapies with psychosocial elements, as supported by recent literature.

References:

- Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV—Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1257-1261.

- Kuo M. How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1093.

- Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(8):506-514.

- Gardner JD, Sloan S, Miner PB, Robinson M. Meal-stimulated gastric acid secretion and integrated gastric acidity in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(7):945-953.

- Bonaz B, Picq C, Sinniger V, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation: from epilepsy to the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(3):208-221.

- Montiel-Castro AJ, González-Cervantes RM, Bravo-Ruiseco G, Pacheco-López G. The microbiota-gut-brain axis: neurobehavioral correlates, health and sociality. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013;7:70.

- Rahimi R, Abdollahi M. Herbal medicines for the management of irritable bowel syndrome: a comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(7):589-600.

- Scholey A, Gibbs A, Neale C, et al. Anti-stress effects of lemon balm-containing foods. Nutrients. 2014;6(11):4805-4821.

- Joukar S, Zarisfi Z, Sepehri G, Bashiri A. Efficacy of Melissa officinalis in suppressing ventricular arrhythmias following ischemia-reperfusion of the heart: a comparison with amiodarone. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23(4):340-345.

- Kim IH, Kim C, Seong K, et al. Essential oil inhalation on blood pressure and salivary cortisol levels in prehypertensive and hypertensive subjects. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:984203.

- Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL. Starving our microbial self: the deleterious consequences of a diet deficient in microbiota-accessible carbohydrates. Cell Metab. 2014;20(5):779-786.

- Bercik P, Collins SM, Verdu EF. Microbes and the gut-brain axis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(5):405-413.

- Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What Is New in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23(2):151-163.

- Youssef NN, Rosh JR, Loughran M, et al. Treatment of functional abdominal pain in childhood with cognitive behavioral strategies. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39(2):192-196.

- Niv E, Halak A, Tiommny E, et al. Randomized clinical study: Partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG) versus placebo in the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2016;13:10.

- Costa RJS, Snipe RMJ, Kitic CM, Gibson PR. Systematic review: exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome-implications for health and intestinal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(3):246-265.

- Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, et al. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010;104 Suppl 2:S1-S63.

- Gao XW, Mubasher M, Fang CY, et al. Dose-response efficacy of a proprietary probiotic formula of Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285 and Lactobacillus casei LBC80R for antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea prophylaxis in adult patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(7):1636-1641.

- Dylewski J, Psaradellis E, Sampalis J. Efficacy of BIO K+ CL1285 in the reduction of antibiotic-associated diarrhea – a placebo controlled double-blind randomized, multi-center study. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6(1):56-64.

- Chedid V, Dhalla S, Clarke JO, et al. Herbal therapy is equivalent to rifaximin for the treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014;3(3):16-24.

- Loc-Carrillo C, Abedon ST. Pros and cons of phage therapy. Bacteriophage. 2011;1(2):111-114.

- Stein T. Bacillus subtilis antibiotics: structures, syntheses and specific functions: Bacillus subtilis antibiotics. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56(4):845-857.

- Hornby PJ, Prouty SM. Involvement of cannabinoid receptors in gut motility and visceral perception. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141(8):1335-1345.

- Sharkey KA, Wiley JW. The Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Brain–Gut Axis. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(2):252-266.

- Ng SC, Lam YT, Tsoi KK, et al. Systematic review: the efficacy of herbal therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(8):854-863.

Image Copyright: <a href=’https://www.123rf.com/profile_antonioguillem’>antonioguillem / 123RF Stock Photo</a>

Matt Marturano, ND, is a naturopathic physician with a keen interest in the human gut microbiome and digestive system. Dr Marturano’s educational background includes an undergraduate degree in biology and philosophy from the University of Michigan, and a doctorate of naturopathic medicine from the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine. He currently conducts lectures, webinars, and trainings on an open-source method for the natural treatment of functional digestive disorders. He is also a managing partner for Orchid Holistic Search, a boutique executive search company focused in the natural products industry.

Matt Marturano, ND, is a naturopathic physician with a keen interest in the human gut microbiome and digestive system. Dr Marturano’s educational background includes an undergraduate degree in biology and philosophy from the University of Michigan, and a doctorate of naturopathic medicine from the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine. He currently conducts lectures, webinars, and trainings on an open-source method for the natural treatment of functional digestive disorders. He is also a managing partner for Orchid Holistic Search, a boutique executive search company focused in the natural products industry.