A Scientific Education: Part 2

FRASER SMITH, MATD, ND

No matter the obstacles they place, the truth of our medicine will win out.

(John Bastyr)1

If we take the phrase “modern world” to denote the advent of a society using technology at a higher level than ever seen, based on an explosion in the growth of pure and applied sciences, the timeframe for that seems to be the later-19th century to the present. Much is taking shape right now in science, including the advancement of computing powers (the implications of that for naturopathic medicine is the focus of next month’s column). The birth of the 20th century ushered in many achievements, including the exact identification of the pathways of metabolism, the elucidation of the physiological bioregulatory systems, the role of DNA and the nature of genes, and much more. Much of today’s health care – even if a microprocessor plays the role of mediator and the molecular diagnostics are far more precise – is based on technology from 100 years ago.

In last month’s column, we looked at how allopathic medicine rode this wave. The ascent of allopathic medicine was both transformative and opportunistic. There is no doubt that the biomedical sciences opened a door to a powerful model of therapeutics, be it antibiotics, cortisol to treat Addison’s, or diuretics to lower blood pressure. At the same time, the allopathic profession seized the high ground in cultural authority, to the point that they nearly extinguished (in North America, at least) all rivals and came to have their opinions be almost unquestioned by the average patient.

A New Foundation

When “naturopathic medicine” arose from the remnants of the naturopathy movement, one of the new features was a solid basic science curriculum. The “2 + 2” model (2 years of basic sciences, laboratory medicine, and diagnosis, followed by clinical sciences taught at the bedside), had become the de facto template for medical education. Donald Schon referred to this as a “normative curriculum.”2 So, if naturopathic medicine were to populate a re-emergent profession with doctors practicing naturopathic medicine, then a foundation of basic sciences and science-based diagnosis had to be the concrete foundation of the house.

This is what happened, and over time the caliber of instruction for naturopathic students caught up to their allopathic counterparts, and in some instances surpassed it (anatomy at our schools is now far more rigorous than that at some schools training medical doctors). In 1996, Dr Clyde Jensen, then President of the National College of Naturopathic Medicine (NCNM, now NUNM), published a paper in the Journal of Complementary and Alternative Medicine entitled “Common Pathways in Medical Education.”3

Achieving Parity

The esteemed Dr Jensen showed, numerically, the significant similarities between medical, osteopathic, and naturopathic medical hours in sciences, pharmacology, diagnosis, and treatment. Of course, these disciplines were very divergent at the 3rd year, but the foundation was remarkably similar in terms of scientific basis. It was clear that naturopathic education had other critical elements, such as clinical theory, nutrition, botanical medicine, etc, that formed the alloy of naturopathic medical training. At Dr Jensen’s behest, a group of us have updated the article and are submitting it to the same journal. In 25 years, the naturopathic strengths in the biomedical sciences have not diminished at all compared to medical and osteopathic training. And in terms of educating doctors who are skilled in nutrition and prevention, naturopathic medicine is clearly in a different league (this author’s opinion).

A Need for Progress

That being made clear, naturopathic medicine would seem to be in the same lane as allopathic medicine – nothing left to do but flip on the cruise control and make refinements as the science continues to grow. Alas, nothing could be further from the truth. Replicating an education model of days gone by is the most comfortable and also the most inopportune thing we can do.

The reasons for the risks inherent in what is intrinsically a good and noteworthy achievement are several. As is so often the case in life, change is the constant. That doesn’t mean that the tried and true have to be discarded in favor of the novel; however, any school, any business, and any doctor, does need to keep up with the world. As an example, in the allopathic education system there is a still a progression from basic sciences to clinical sciences; however, the former has been compressed to allow for more time in actual clinical training. The idea is to provide the fundamentals to enter the training “job market” as a resident and to equip the student with the skills to learn more on their own or under guidance. Nobody would seriously propose teaching medical students the whole field.

Science and Practice

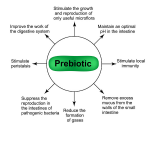

The emphasis of that science – preparing the allopathic student for pharmacotherapy versus the empirical, whole-person approach – is another matter. Naturopathic medical students need to understand and apply the biomedical sciences to skills such as diagnosis and pharmacotherapy (at the very least, knowing how it works). Unlike their allopathic counterparts, naturopathic students are also learning about the application of the biomedical sciences in other ways, in tandem with the standard medical approach. In one sense, we are looking at the changes in physiology that happen when the body is under duress and how we might support that crumbling physiology even if that support is not ultimately curative. An example would be giving a person with congestive heart failure the supplement coenzyme Q10. We know that in some clinical trials, it helps with quality of life. We also know that it can be poorly supplied in the ailing heart. It is intrinsic to the function of mitochondria, and it might be depressed in those receiving intensive statin therapy. So we supplement it, not as a “cure” for congestive heart failure, but to support a weakened and compensated system.

Another way in which we use the biomedical sciences is to trace the symptoms of a patient to a disordered underlying physiology that probably arose due to disturbances to the determinants of health. Yet another is to think about how multiple systems interact; a supplement that supports hepatic biotransformation of hormones is an example. The seeming dichotomy between a mechanistic approach to understanding health and disease and a less reductionistic and more system-based approach to practice is an educational challenge. But practicing naturopathic doctors straddle these 2 modes of thinking every day. Still, the naturopathic curriculum cannot be a simulacrum of allopathic education, for this reason alone.

Evidence-Based Medicine

In the early 2000s, another, quieter, revolution was taking place in the application of science to health care. This was the Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) movement,4 which can be described as the intersection of easy-to-access databases of studies, as well as refinements in the appraisal of studies. Evidence was increasingly ranked, with systematic reviews as a way to overcome the limitations in a single study, and meta-analyses began to synthesize data from multiple studies. These were good advances. Medline and similar databases went from something that was used at a library and was updated monthly from a disc, to a frequently-updated database that was accessible from the World Wide Web. Search filters and various Boolean operators could help the physician find the needle in the haystack of studies, or at least get pretty close.

Three new elements had to be added to the naturopathic education. One was the simple proficiency in using these databases. Another was an understanding of the hierarchy of evidence-based medicine (healthcare) and how that evidence fits in with clinical judgment and biomedical sciences (the original 3-legged stool of EBM). And finally, the student had to know how to apply these skills to patient care.

This is an important skill for naturopathic physicians, but it must be approached with confidence, not naiveté. For one thing, the arrival of new tools for eliminating bias from research and ways to access that research are not at a state of perfection. Critics of the “gold standard” of research, such as John Ioannidis of Stanford, are quick to point out how so much of the research in even top-tier journals falls short.5 This doesn’t mean we should ignore it or – even worse – cast aspersion on some of the best practices in research. But it reminds us in naturopathic medicine that we should not be overawed or intimidated by the randomized control trial and systematic review complex.

Don’t Discard Judgment and Experience

Another thing to keep in mind is that much of medical practice is empirical and based on clinical judgment informed by best evidence. That was the original intent of the EBM movement. It was perhaps inevitable that this would progress to a belief that absolute answers about treatment could be yielded if just enough data could be crunched fast enough. That vision has remained elusive even for well-trodden therapies such as statins. The temptation for naturopathic education is to too strictly model ourselves after this extreme meta-analysis approach, and the result would be a rather sad species of “wannabee” that won’t do for as fine a group as our naturopathic profession. The naturopathic programs in North America have done a fine job of synthesizing EBM, tradition, and a very observational and patient-centered model.

One other reason that even the top-tier research coming from a more allopathic model of care is perennially incomplete for our purposes is that it is really best suited for an allopathic approach. That goes something like this: “Here is a definable lesion or therapeutic target, here is the specific treatment, and here is the outcome.” That is valuable to discover, but naturopathic medicine is equally invested in understanding open, whole systems. That is to say, much of what appears as health and disease is the outcome of many interacting variables in a single person, and that person is influenced by many environmental factors, and in a very fluid way. The accumulation of evidence about LDL-cholesterol as the therapeutic target for preventing atherosclerosis is a good example. One interventional cardiologist told me, “Like my colleagues, I have drunk the Koolaid around LDL and statins.” This translates roughly as, “It’s the cholesterol, Stupid!” and statins are the best tool we have to lower it. As a naturopathic physician, I see those correlations too, and the value of ASCVD prevention guidelines make sense.6 Those guidelines do include risk factors. But I also am aware that the lethality of LDL depends on things like long-term circulating insulin levels, antioxidant status, omega-6 intake, vitamin D status, overall inflammation, and lipoprotein characteristics. In fact, the newest research is showing that depressed LDL levels are associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality.7 So, the heroic measures to pound LDL into the ground with intensive statin therapy may be for naught. The lesson for naturopathic education is that our job is not to make students “drink the Koolaid,” but to make them critical thinkers who understand and accept that whole systems, open systems, and really, individual humans, have to be approached with a sophisticated therapeutic sensibility (Tolle totum).

A Scientific Foundation

Finally, there is an even more powerful argument for maintaining some independence in this matter of science. That is the principle that naturopathic medicine is inherently scientific because it is based on bringing the patient into harmony with the laws of nature, the laws of health, and helping to right dysregulated systems in the body. It is that branch of medicine that was designed to restore the conditions for health and to help the candle burn more brightly. It is just 1 branch of medicine, but an ancient one with a bright future.

When I was a new student, the great Dr John Bastyr came to visit us at CCNM (1993, I believe), at which point he was well into his 80s. The whole student body gathered in the gym. Dr Bastyr told us how he still read 2 scientific articles each night, and he kindly and effortlessly answered questions from some of the interns. I can no longer recall if he said the following then, or if I subsequently read it, or both, but he stated that being based on science, naturopathic medicine would be vindicated by advances in science (I heavily paraphrase). That is the heart of the matter: that science is something we should embrace and that we have a duty to champion a therapeutic approach where “the patient does the healing,” as Dr Bastyr would say. That kind of scientific education fills a void in health care, which is what inspired many of us to follow this path. Claiming the use of the science of today within a whole-person healing approach makes a fitting basis for the education of naturopathic doctors.

In next month’s column, we’ll explore what this means for the possible science of tomorrow, which will be no less dramatic in its transformative effects on medicine.

References:

- Goldman E. John Bastyr: Physician, Healer, Mentor. November 20, 2018. Holistic Primary Care Web site. https://holisticprimarycare.net/topics/naturopathic-perspective/john-bastyr-physician-healer-mentor/. Accessed February 16, 2021.

- Neumann RK Jr. Donald Schön, The Reflective Practitioner, and The Comparative Failures of Legal Education. Spring 2000. Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/519. Accessed February 16, 2021.

- Jensen CB. Common Paths in Medical Education: The Training of Allopaths, Osteopaths, and Naturopaths. Altern Complement Ther. 2009;3(4):276-280. Available at: http://doi.org/10.1089/act.1997.3.276. Accessed February 16, 2021.

- Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet. 2017;390(10092):415-423.

- Ioannidis JP. Why Most Clinical Research Is Not Useful. PLoS Med. 2016;13(6):e1002049.

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. Erratum in: Circulation. 2019;140(11):e649-e650. Erratum in: Circulation. 2020;141(4):e60. Erratum in: Circulation. 2020;141(16):e774.

- Jeong SM, Choi S, Kim K, et al. Association of change in total cholesterol level with mortality: A population-based study. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0196030. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215934

Fraser Smith, MATD, ND is Assistant Dean of Naturopathic Medicine and Professor at the National University of Health Sciences (NUHS) in Lombard, IL. Prior to working at NUHS, he served as Dean of Naturopathic Medicine at the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM) in Toronto, Ontario. Dr. Smith is a licensed naturopathic physician and graduate of CCNM.