Preconception Care Priming Women for a Healthy Pregnancy

Jaclyn Chasse, ND

Whether or not a couple is struggling to conceive, proper preparation for pregnancy is essential to ensure that the health of the baby is maximized. When a couple has had difficulty conceiving or carrying to term, preconception care can make all the difference. A study conducted by the Forsight Group – a UK-based nonprofit dedicated to promoting preconception care – followed 367 couples ranging in age from 22 to 59. Many couples in the study had a previous history of infertility (37% of couples), miscarriage (38%), therapeutic abortion (11%), stillbirth (3%), low birth weight babies (15%), malformations (2%), and SIDS (1%).1 All couples received basic preconception care including nutritional counseling and a prenatal multivitamin for both partners. After 2 years, 89% of the couples had achieved live births. Of those with previously-diagnosed infertility, 81% achieved live births, suggesting that lifestyle modification may positively impact fertility. Also of note is that within this treatment group, there were no reported miscarriages, perinatal deaths or malformations, and most children were born full-term and of a healthy weight.1As naturopathic physicians, we practice and live according to the naturopathic principles – first do no harm, doctor as teacher, prevention, etc. It’s this last principle – prevention – which spurs considerable interest in the topic of preconception care. Increasing evidence is demonstrating that the environment in which a child is conceived, as well as the in-utero environment, strongly influence the health outcomes of both the pregnancy and the offspring throughout that individual’s lifetime. This topic was discussed in my NDNR article entitled “Infants, Tweens, and Teens: Do they Hold the Keys to Our Healthy Future?” published in September, 2012.

Starting at the Beginning

Several lifestyle factors have been identified which can promote optimal fertility, including dietary behaviors, stress management, and maintenance of a healthy weight. In addition, adequate nutrient status can influence not only the ability to get pregnant, but the health of the egg and sperm, and thus the health of the child born to those parents. The following interventions can greatly influence fertility, and it is recommended that all couples trying to conceive consider these interventions, whether or not they have trouble with fertility.

Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet is a dietary recommendation based on the traditional dietary patterns of Crete and the rest of Greece, southern Italy, and southern France.2 The diet emphasizes an abundance of plant foods, especially fruits and vegetables, and a low intake of red meat. Generally, fat makes up 25-35% of total calories, with low intake of saturated fats and high intake of monounsaturated fats, such as that found in olive oil and omega-3 fats, as found in cold-water fish. The primary fats consumed in this diet come from fish, poultry, and olive oil. The diet is high in legumes and whole grains, and suggests low-to-moderate consumption of dairy products and red wine.

The Mediterranean diet has, of course, been studied for its positive effects on cardiovascular disease and overall mortality.3 It has been researched for its effects on diabetes, depression, cognitive function, cancer, weight loss, and much more.4 Of note for this article is the diet’s effect on fertility. Observation of 2154 Spanish women, aged 20-45 years, showed that those women with the greatest adherence to a Mediterranean diet pattern (versus a Western diet) had the least amount of difficulty in getting pregnant.5 Additionally, a 2010 study of 161 Dutch couples undergoing in-vitro fertilization (IVF) or in-vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF with ICSI) found that Mediterranean diet adherence increased the probability of pregnancy (odds ratio, 1.4).6 In the same study, adherence to the Mediterranean diet was also associated with higher folate and vitamin B6 levels in red blood cells and in follicular fluid.

Addressing Obesity

Obesity poses a significant threat to fertility, as well as to the offspring born to obese parents. Obese men have increased aromatase activity, which irreversibly converts testosterone to estradiol; this results in decreased testosterone and increased estrogen levels.7 It is likely that this plays a role in the lower sperm counts, lower sperm concentration, and poor sperm morphology seen in men with increased body mass index (BMI) and central adiposity. Obese men also have fewer motile sperm and lower testosterone levels, as mentioned above.8,9

It’s not only men who experience decreased fertility as their weight creeps up; women are also affected. Compared to non-obese women, obese women undergoing IVF have lower pregnancy rates (20.8% vs 28.3% successful cycles; p=0.04); obese women are more likely to experience preterm births after IVF.10-12 Although these studies represent women undergoing IVF, similar fertility trends exist in women trying to conceive naturally.13 Together, obese couples experience higher rates of miscarriage in both spontaneous conception and assisted reproduction.14 In addition to the hormonal changes noted for men, this decrease in fertility may be due to an increased level of inflammation, which affects ovarian response and the uterine/endometrial environment.

Obesity poses such a hindrance to fecundity that many fertility clinics place a BMI limit for candidacy for the procedure. Addressing obesity for patients is essential for supporting a healthy conception and pregnancy, and maintenance of a healthy weight should be a primary goal for couples wishing to get pregnant. If a weight loss plan is implemented, it is strongly recommended that clinicians consider promoting a modified Mediterranean diet, as this diet also has fertility-promoting effects.

Stress Management

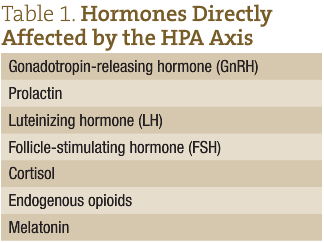

Stress has a documented impact on fertility. Studies have confirmed that stress inhibits the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis.15 The stress hormones cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis directly interact w ith several other hormones, including hormones that regulate the menstrual cycle and gamete maturation (Table 1). Stress can modify levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which directly impact synthesis of estrogen and progesterone, and dictate follicular maturation and ovulation in women and spermatogenesis and testosterone production in men. Elevated cortisol and ACTH in men can also inhibit the conversion of androstenedione into testosterone in Leydig cells.16 Higher follicular cortisol/cortisone ratios are associated with higher rates of infertility in women.17 It has been noted that men with increased stress have a decrease in glutathione and free sulphydryl content of semen, both of which are important for combating oxidative stress and toxic exposure.18

ith several other hormones, including hormones that regulate the menstrual cycle and gamete maturation (Table 1). Stress can modify levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which directly impact synthesis of estrogen and progesterone, and dictate follicular maturation and ovulation in women and spermatogenesis and testosterone production in men. Elevated cortisol and ACTH in men can also inhibit the conversion of androstenedione into testosterone in Leydig cells.16 Higher follicular cortisol/cortisone ratios are associated with higher rates of infertility in women.17 It has been noted that men with increased stress have a decrease in glutathione and free sulphydryl content of semen, both of which are important for combating oxidative stress and toxic exposure.18

Interestingly, the link between stress and female fertility goes beyond an increase in stress hormone levels and their downstream effects. Hans Selye observed ovarian atrophy in response to stress in rats.19 It is important to acknowledge that stress mediators can be protective, not just damaging, though high levels can lead to allosteric overload, where there is a high likelihood of changes to the physiological systems that affect fertility.20

It seems that various methods of stress management and counseling may be successful for couples trying to conceive. Mind/body intervention increased IVF pregnancy rates from 43% to 52% in a group of women under 40 who were about to start their first IVF cycle at a Massachusetts fertility clinic.21 Additionally, “letting go” counseling, focused around releasing control of the process of conception, has also shown to be beneficial. This type of counseling nearly doubled pregnancy rates in the treatment group.22 Many other interventions have shown benefit for both men and women, including standard psychotherapy.

It is essential for practitioners to work with patients to develop a stress-management protocol that will work for each couple, and to be sensitive to the fact that a robust treatment plan may create an increased focus on infertility and, therefore, an increase in stress, in and of itself.

Basic Preconception Supplementation

In this author’s opinion, every couple trying to conceive should be put on a basic preconception supplement regimen. Specific nutrients, such as folic acid, have been shown to be beneficial for not only preventing serious birth defects like spina bifida, but also for negating deleterious epigenetic effects to the offspring of parents with toxic exposures, poor nutrition, and elevated stress levels.23 No couple lives in a perfect world; however, these extra precautions may not only promote fertility, but may also have a significant impact on the offspring’s adult health status. The most simple preconception program would include a good multivitamin and fish oil for both partners.

A prenatal multivitamin provides key nutrients necessary for both mom and baby throughout fetal development. These include iron, calcium, folate, and zinc. Studies have demonstrated significantly improved pregnancy rates in women on multiple micronutrient supplements, compared to folic acid alone (66.7% vs 39.3% achieved conception after 3 menstrual cycles; the ongoing pregnancy rate was 60% vs 25%).24 Compared to consumption of folic acid and iron alone, consumption of a prenatal multivitamin has also been associated with significantly improved birth outcomes, including healthier birth weight of babies, and decreased rates of stillbirth and miscarriage. A nonsignificant trend of decrease in neonatal deaths has also been observed.25 Not surprisingly, the same study also reported that mothers who took a prenatal vitamin had better micronutrient status postpartum.

Fish oil is another key supplement to include in a preconception protocol for every couple who is contemplating pregnancy within the next 6 months. It has been observed that, compared with infertile men, fertile men tend to have higher blood and spermatozoan levels of omega-3 fatty acids, as well as lower serum ratios of omega-6 to omega-3.26 For men with oligoasthenoteratospermia (OAT) – the worst semen parameters possible – supplementation with omega-3s significantly improved semen parameters, including increasing sperm count from 38.7 to 61.7 million semen, and increasing sperm concentration from 15.6 to 28.7 million/mL.27 It is clinically useful to understand that a sperm concentration greater than 20 million/mL is associated with a much higher rate of clinical pregnancy compared to below 20 million/mL, where the likelihood of natural conception is considered to be approximately zero.28 This fact further emphasizes fish oil benefits. Fish oil supplementation has also been correlated with increased superoxide dismutase (SOD)-like and catalase-like activity (both of which promote an increased ability to withstand oxidative stress), as well as positive, nonsignificant improvements in sperm motility and morphology.27

While there are fewer studies validating the benefit of omega-3 supplementation in women, it is fair to assume that the significant benefits to gamete production in men would have some correlation to the analogous structure in a woman, the egg. Increased dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids in women, especially alpha-linolenic and docosahexaenoic acids (DHA), have been correlated with an improvement in embryo morphology in couples undergoing IVF with ICSI.29

Case Study

Jane, a 35-year-old woman, with no prior pregnancies, comes into the clinic hoping to get pregnant. She knows that she is approaching the age where there are increased risks of trisomies and other genetic abnormalities; thus, she would like to increase her chances of a healthy pregnancy and baby. Jane is a kindergarten teacher, modestly overweight (BMI=28), and eats a standard American diet. She describes her stress as moderate and doesn’t have any formal exercise, although she notes that she spends her day chasing 6-year-olds. She and her husband, Nick, have been trying to conceive for 2 months. Neither partner has been evaluated for infertility, as there has been no need to-date.

Recommendations for Jane (and her husband)

Mediterranean Diet: Jane and Nick were provided a handout and 20 minutes of dietary counseling on the Mediterranean diet, including a 1-week, plant-strong meal plan. This meal plan provided meals focused around plant-based proteins (beans, lentils, legumes, quinoa) plus healthy fish, and limited intake of sugars, meats, and animal proteins. The discussion also included the importance of organic food, clean water, and avoidance of xenoestrogens and, specifically, bisphenol-A (BPA).

Exercise: Each partner was instructed to get a minimum of 2 hours per week of exercise, plus a minimum of 20 minutes of walking daily. They loved this instruction and discussed that they would do after-dinner walks together.

Supplementation (Jane): Jane was prescribed a prenatal multivitamin (containing 800 µg methylfolate, 25 mg zinc, 15 mg iron, and 400 IU vitamin D) and fish oil (2000 mg of EPA + DHA daily; fish oil also contained 2000 IU of vitamin D). Due to her “advanced age,” she was also encouraged to include an extra boost of colorful fruits and veggies daily. She chose to do this through a reds/greens functional food powder that also contained turmeric root.

Supplementation (Nick): Nick was prescribed a high-quality multivitamin containing 1000 IU vitamin D, 25 mg zinc, 200 µg selenium, and 50 mg CoQ10, as well as fish oil (2000 mg EPA + DHA).

The couple was counseled on cycle-charting and fertility signs, and optimal time to attempt conception, and were encouraged to stay on this plan for 3-4 months prior to returning to the office.

Follow-up

After 3 cycles, Jane scheduled a follow-up visit to share the news that they were pregnant, also to discuss her changing nutritional needs… and address nausea.

Jaclyn Chasse, ND, is a practicing naturopathic doctor in New Hampshire, and the medical director at Emerson Ecologics. She also holds an adjunct faculty position at Bastyr University, teaching courses on reproductive endocrinology. Dr Chasse’s clinical practice focuses on women’s health, especially infertility, and pediatrics (a natural extension of treating infertility!). In 2012, she was honored by being named Leading Physician in Alternative Medicine by NH Magazine. Dr Chasse has been very involved throughout her professional career in improving healthcare access and education. As a medical student, she co-founded the Naturopathic Medical Student Association, now an affiliate branch of AMSA. She is the immediate past-president of the New Hampshire Association of Naturopathic Doctors and currently serves on the boards of the American Herbal Products Association, the Endocrinology Association of Naturopathic Physicians, and the AANP Board of Directors, where she will take office as President in January, 2016.

Jaclyn Chasse, ND, is a practicing naturopathic doctor in New Hampshire, and the medical director at Emerson Ecologics. She also holds an adjunct faculty position at Bastyr University, teaching courses on reproductive endocrinology. Dr Chasse’s clinical practice focuses on women’s health, especially infertility, and pediatrics (a natural extension of treating infertility!). In 2012, she was honored by being named Leading Physician in Alternative Medicine by NH Magazine. Dr Chasse has been very involved throughout her professional career in improving healthcare access and education. As a medical student, she co-founded the Naturopathic Medical Student Association, now an affiliate branch of AMSA. She is the immediate past-president of the New Hampshire Association of Naturopathic Doctors and currently serves on the boards of the American Herbal Products Association, the Endocrinology Association of Naturopathic Physicians, and the AANP Board of Directors, where she will take office as President in January, 2016.

References

- Ward N, Eaton K. Preconceptional care and pregnancy outcome. J Nutr Env Med. 1995;5(2):205-207.

- Kushi LH, Lenart EB, Willett WC. Health implications of Mediterranean diets in light of contemporary knowledge. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(6 Suppl):1407S-1427S.

- Knoops KT, deGroot LC, Kromhout D, et al. Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors, and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women: the HALE project. JAMA. 2004;292(12):1433-1439.

- Martinez-Gonzales MA, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Nunez-Cordoba JM, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7657):1348-1351.

- Toledo E, Lopez-del Burgo C, Ruiz-Zambrana A, et al. Dietary patterns and difficulty conceiving: a nested case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(5):1149-1153.

- Vujkovic M, de Vries JH, Lindemans J, et al. The preconception Mediterranean dietary pattern in couples undergoing in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment increases the chance of pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2096-2101.

- Cohen, PG. Obesity in men: the hypogonadal-estrogen receptor relationship and its effects on glucose homeostasis. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70(2):358-360.

- Sermondade N, Faure C, Fezeu L, et al. Obesity and increased risk for oligozoospermia and azoospermia. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):440-442.

- Hakonsen LB, Thulstrup AM, Aggerholm AS, et al. Does weight loss improve semen quality and reproductive hormones? Results from a cohort study of severely obese men. Reprod Health. 2011;8:24.

- Pinborg A, Gaarsley C, Hougaard CO, et al. Influence of female bodyweight on IVF outcome: a longitudinal multicentre cohort study of 487 infertile couples. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23(4):490-499.

- Kumbak B, Oral E, Bukulmez O. Female obesity and assisted reproductive technologies. Semin Reprod Med. 2012;30(6):507-516.

- Dickey RP, Xiong X, Gee RE, et al. Effect of maternal height and weight on risk of preterm birth in singleton and twin births resulting from in vitro fertilization: a respective cohort study using the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcome Reporting System. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(2):349-354.

- Cardozo ER, Neff LM, Brocks ME, et al. Infertility patients’ knowledge of the effects of obesity on reproductive health outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(6):509.

- Boots C, Stephenson MD. Does obesity increase the risk of miscarriage in spontaneous conception: a systematic review. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(6):507-513.

- Berga SL. Functional hypothalamic chronic anovulation. In: Adashi EY, Rock JA, Rosenwaks Z , eds. Reproductive Endocrinology, Surgery and Technology. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996; pg 1061-1076.

- Klimek M, Pabian W, Tomaszewska B, et al. Levels of plasma ACTH in men from infertile couples. Neur Endocrinol Lett. 2005;26(4):347-350.

- Arcuri F, Monder C, Lockwood CJ, et al. Expression of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase during decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. Endocrinology. 1996;137(2):595-600.

- Eskiocak S, Gozen AS, Yapar SB, et al. Glutathione and free sulphydryl content of seminal plasma in healthy medical students during and after exam stress. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(9):2595-2600.

- Sanders KA, Bruce NW. Psychological stress and treatment outcome following assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(6):1656-1662.

- McEwen BS. Stressed or stressed out: what is the difference? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005;30(5):315-318.

- Domar A, Rooney KL, Wiegand B, et al. Impact of a group mind/body intervention on pregnancy rates in IVF patients. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(7):2269-2273.

- Rapoport-Hubschman N, Gidron Y, Reicher-Atir R, et al. “Letting go” coping is associated with successful IVF treatment outcome. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(4):1384-1388.

- Torrens C, Brawley L, Anthony FW, et al. Folate supplementation during pregnancy improves offspring cardiovascular dysfunction induced by protein restriction. Hypertension. 2006;47(5):982-987.

- Agrawal R, Burt E, Gallagher AM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of multiple micronutrients in subfertile women undergoing ovulation induction: a pilot study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;24(1):54-60.

- Sunawang, Utomo B, Hidayat A, et al. Preventing low birth weight through maternal micronutrient supplementation: a cluster-randomized, controlled trial in Indramayu, West Java. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30(4 Suppl):S488-S495.

- Safarinejad MR, Hosseini SY, Fafkhah F, et al. Relationship of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids with semen characteristics, and anti-oxidant status of seminal plasma: a comparison between fertile and infertile men. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(1):100-105.

- Sarafinejad MR. Effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on semen profile and enzymatic antioxidant capacity of seminal plasma in infertile men with idiopathic oligoasthenoteratospermia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Andrologia. 2011;43(1):38-47.

- Strauss JF, III, Barbieri RL. Yen & Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2009.

- Hammiche F, Vujkovic M, Wijburg W, et al. Increased preconception omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake improves embryo morphology. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(5):1820-1823.