NAFLD: Hepatic Manifestation of Metabolic Syndrome

Asia Muhammad, ND

Tolle Causam

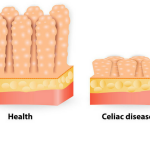

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome (MetS). NAFLD (also referred to as NASH, or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) constitutes a spectrum of simple steatosis, steatohepatitis, and cirrhosis.1,2 Approximately 20-30% of Americans have NAFLD.1,3

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of NAFLD is often described as a 2-hit theory. The first hit is an accumulation of fatty acids (steatosis) by multiple mechanisms, such as hyperinsulinemia, reduced VLDL secretion from the liver, and increased hepatic synthesis of free fatty acids. The major source for triglyceride deposition in the liver is endogenous fat stores, not dietary fat.1 The second hit is peroxidation of these fatty acids. This occurs via various cytokine and reactive oxygen species interacting with the accumulated fats.1

Approximately 20% of simple steatosis patients will progress to steatohepatitis, a condition associated with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma3; it has been estimated that 20% of steatohepatitis patients will progress to cirrhosis.1 There is no singular predictive mechanism linked with the progression from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis to cirrhosis. In one study, MetS was found in 88% of steatohepatitis patients.4 Of note, there is a rising occurrence of “lean NAFLD” in patients who are normal weight.

Diagnosis

The majority of NAFLD cases are found incidentally on ultrasound, CT, and MRI; however, liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis.1 On biochemical assessment, an ALT value that is higher than the AST value points toward fatty liver disease once other causes of elevated transaminases have been ruled out, including viral hepatitis. Transaminases are not sensitive enough to diagnose and histologically stage NAFLD. In one study 60% of patients with steatohepatitis had normal transaminases, while over 53% of patients without steatohepatitis had elevations in serum transaminases.2 Gastroenterologists and hepatologists are predicting that, within the next 15-20 years, the leading indicator for liver transplantation will be NAFLD-related liver disease, displacing hepatitis C- and alcoholism-related liver transplants.5

Treatment

Role of Soft Drinks & Fructose

Currently, there is no FDA-approved drug for NAFLD. The current treatment recommendation is dietary and lifestyle modification. Soft drink consumption is associated with fatty liver. In one study, soft drink consumption as a predictor of fatty liver disease was associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.0 (p<0.04).6

High fructose intake is also associated with fatty liver disease.7 Fructose is not metabolized in the same rate-limiting manner as glucose. Specifically, rather than being metabolized by phosphofructokinase, the rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis, fructose is metabolized by fructokinase. In nature, fructose is found in concentrations of 5-10% in fruits. In contrast, high-fructose corn syrup has a fructose content that can range from 50% to 90%. Excessive intake of fructose promotes fatty acid synthesis via an unregulated source of 3-carbon molecules, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, and dihydroxyacetone phosphate, to be used for fatty acid synthesis. Insulin, ghrelin, and leptin are important hormones that regulate carbohydrate metabolism and appetite. Fructose does not stimulate these hormones in the same manner as glucose. Fructose not only leads to fat accumulation in the liver; it is also associated with adipose accumulation in peripheral tissues.

Weight Loss

Weight loss and diet appear to be the most powerful combination for reversing NAFLD and reducing the odds of fibrosis.6-8 Weight loss of 7-10% body weight, along with improvements in transaminases, is associated with histological improvement of the liver.9-12 In a study of 293 biopsy-confirmed NASH patients, 90% of those who lost 10% or more of their body weight experienced resolution of NASH.9 In this same study, those who lost >5% body weight experienced a 2-point reduction in the histological NAFLD Activity Score.

NAFLD Medications

Several studies have shown metformin to reduce transaminases but not improve liver histology.13-15 Pioglitazone has been observed to improve liver histology and serum aminotransferases, and increase hepatic insulin sensitivity; however, risks associated with long-term thiazolidinediones may outweigh the benefits.15-17 Elafribranor and obeticholic acid are 2 contenders in clinical trials, as both are associated with significant improvement in histological features of NAFLD.18,19

Natural Agents

In small studies, omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to improve transaminases, reduce liver fat (as evidenced by ultrasound), and improve liver histology; larger studies are needed for confirmation.20-22 Vitamin E, 800 IU daily, significantly improved liver histology of NAFLD patients, as compared to placebo.17 In the liver, phosphatidylcholine is required to process and package triglycerides into VLDLs.1,23 Phosphatidylcholine is sourced 2 ways in humans. One source is diet; the other source is de-novo biosynthesis, catalyzed by phosphatidyl-ethanolamine-N-methyltransferase, which is an estrogen-dependent enzyme.1 Phosphatidylcholine supplementation has been shown in many studies to improve liver serology, reduce liver fat, and improve histological features.23,24 Berberine herbs (such as Berberis vulgaris), Silybum marianum (milk thistle), Momordica charantia (bitter melon), and Gynostemma pentaphyllum are a few of the many herbs studied in human and animal models of NAFLD.25-33 Studies, however, are conflicting and many used small patient populations. In one study of 64 ultrasound-confirmed steatohepatitis patients with elevated ALT levels, silymarin, 210 mg X 8 weeks, was associated with a more noticeable reduction of ALT levels as compared with controls.33 Berberine, when compared with pioglitazone, was not significant for reducing liver transaminases; however, when compared with placebo there was significant reduction in hepatic fat content.31

Summary

NAFLD is an increasingly common disorder, affecting 20-30% of Americans. As metabolic syndrome, including insulin resistance, has been observed in the majority of patients with fatty liver, NAFLD may be considered to be a hepatic manifestation of MetS. Several natural agents, in the form of nutraceuticals and botanical therapies have been shown to improve various abnormalities in NAFLD patients. However, weight loss and dietary modification alone may be sufficient for resolving NAFLD. In patients with NAFLD, the goal should be a weight loss of 7-10% body weight, and dietary modification that includes complete elimination of high-fructose corn syrup.

References:

- Tirosh O, ed. Liver Metabolism and Fatty Liver Disease. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2014.

- Fracanzani AL, Valenti L, Bugianesi E, et al. Risk of severe liver disease in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with normal aminotransferase levels: a role for insulin resistance and diabetes. Hepatology. 2008;48(3):792-798.

- Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. 2016;64(1):73-84.

- Bhatt HB, Smith RJ. Fatty liver disease in diabetes mellitus. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2015;4(2):101-108.

- Zezos P, Renner EL. Liver transplantation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(42):15532-15538.

- Abid A, Taha O, Nseir W, et al. Soft drink consumption is associated with fatty liver disease independent of metabolic syndrome. J Hepatol. 2009;51(5):918-924.

- Ouyang X, Cirillo P, Sautin Y, et al. Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2008;48(6):993-999.

- Kistler KD, Brunt EM, Clark JM, et al. Physical activity recommendations, exercise intensity, and histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(3):460-468.

- Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367-378.

- Dixon JB, Bhathal PS, Hughes NR, O’Brien PE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Improvement in liver histological analysis with weight loss. Hepatology. 2004;39(6):1647-1654.

- Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):121-129.

- Palmer M, Schaffner F. Effect of weight reduction on hepatic abnormalities in overweight patients. Gastroenterology. 1990;99(5):1408-1413.

- Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, et al. Metformin in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Lancet. 2001;358(9285):893-894.

- Li Y, Liu L, Wang B, et al. Metformin in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed 2013;1(1):57-64.

- Rakoski MO, Singal AG, Rogers MA, Conjeevaram H. Meta-analysis: insulin sensitizers for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(10):1211-1221.

- Belfort R, Harrison SA, Brown K, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(22):2297-2307.

- Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, et al. Pioglitazone, Vitamin E, or Placebo for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1675-1685.

- Ratziu V, Harrison SA, Francque S, et al. Elafibranor, an Agonist of the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-α and -δ, Induces Resolution of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Without Fibrosis Worsening. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(5):1147-1159.

- Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9972):956-965.

- Capanni M, Calella F, Biagini MR, et al. Prolonged n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation ameliorates hepatic steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(8):1143-1151.

- Tanaka N, Sano K, Horiuchi A, et al. Highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid treatment improves nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(4):413-418.

- Zelber-Sagi S, Ratziu V, Oren R. Nutrition and physical activity in NAFLD: An overview of the epidemiological evidence. World J Gastro. 2011;17(29):3377-3389.

- Gundermann KJ, ed. The “Essential” Phospholipids as a Membrane Therapeutic. Szczecin, Poland: Polish Society of European Society of Biochemical Pharmacology. Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Medical Academy; 1993.

- Gundermann KJ, Gundermann S, Drozdzik M, Mohan Prasad VG. Essential phospholipids in fatty liver: a scientific update. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:105-117.

- Huyen VT, Phan DV, Thang P, et al. Antidiabetic effect of Gynostemma pentaphyllum tea in randomly assigned type 2 diabetic patients. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42(5):353-357.

- Gauhar R, Hwang SL, Jeong SS, et al. Heat-processed Gynostemma pentaphyllum extract improves obesity in ob/ob mice by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Biotechnol Lett. 2012;34(9):1607-1616.

- Cacciapuoti F, Scognamiglio A, Palumbo R, et al. Silymarin in non alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2013;5(3):109-113.

- Salamone F, Galvano F, Cappello F, et al. Silibinin modulates lipid homeostasis and inhibits nuclear factor kappa B activation in experimental nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Transl Res. 2012;159(6):477-486.

- Chen Q, Li ET. Reduced adiposity in bitter melon (Momordica charantia) fed rats is associated with lower tissue triglyceride and higher plasma catecholamines. Br J Nutr. 2005;93(5):747-754.

- Senanayake GV, Maruyama M, Shibuya K, et al. The effects of bitter melon (Momordica charantia) on serum and liver triglyceride levels in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;91(2-3):257-262.

- Yan HM, Xia MF, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy of Berberine in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134172.

- Guo T, Woo SL, Guo X, et al. Berberine Ameliorates Hepatic Steatosis and Suppresses Liver and Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Mice with Diet-induced Obesity. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22612.

- Solhi H, Ghahremani R, Kazemifar AM, Hoseini Yazdi Z. Silymarin in treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized clinical trial. Caspian J Intern Med. 2014;5(1):9-12.

Image Copyright: <a href=’https://www.123rf.com/profile_radub85′>radub85 / 123RF Stock Photo</a>

Asia Muhammad, ND, values the power of lifestyle modifications in the treatment of disease. She uses evidence-based medicine to provide individualized care to each patient. She has special interests in gastroenterology, mind-body medicine, and stress management, as increasing research demonstrates the role of stress in disease. She has received additional training in mind-body therapies, including hypnosis, guided imagery, biofeedback, autogenic training, and progressive muscle relaxation. Dr Muhammad received her doctorate in Naturopathic Medicine from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2014.

Asia Muhammad, ND, values the power of lifestyle modifications in the treatment of disease. She uses evidence-based medicine to provide individualized care to each patient. She has special interests in gastroenterology, mind-body medicine, and stress management, as increasing research demonstrates the role of stress in disease. She has received additional training in mind-body therapies, including hypnosis, guided imagery, biofeedback, autogenic training, and progressive muscle relaxation. Dr Muhammad received her doctorate in Naturopathic Medicine from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2014.