Herbs as Bitters: It’s a Matter of Degree

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH(AHG)

The digestive system is the seat of health and wellness. The immune system is dependent on balance of the gut flora and function. The nervous system, through the gut-brain, plays a critical role in both digestive and overall health. And most nutrients enter the body via digestion and absorption through the gut. The digestive system can also be the seat of dis-ease. Most, if not all, chronic diseases have their root in the lack of proper functioning of the digestive system.

Proper function of the gut, and the promotion of overall general health, begins with appropriate amounts and timing of digestive secretions. The bitter taste plays a significant role in GI secretions. When the bitter taste buds on the tongue are activated, the vagus nerve is stimulated, and a cascade of digestive secretions is initiated.

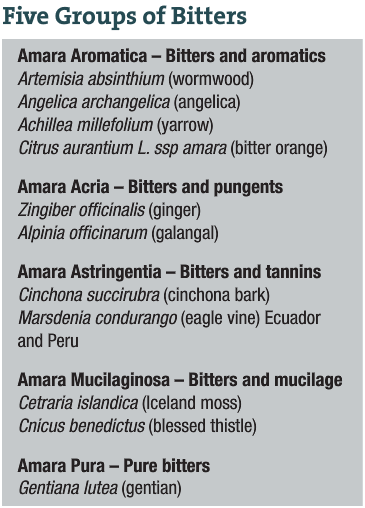

But bitter herbs are not all equal, and patients will not respond the same to all bitter herbs. Therefore, the choice of a bitter herb or formula of bitters for therapeutic use should initially be considered by the state of each patient, whether constitutional or symptomatic. Assessing each patient’s digestive fire, called “agni” in Ayurvedic Medicine, will help to determine the degree of bitterness of herbs to be prescribed. Bitter herbs are generally cooling energetically (Frawley and Lad, 1986). If the agni is strong, it can be matched with a stronger bitter. If the agni is weak, it will need to be matched with a bitter that works a bit more gently to get the desired effects of stimulating the digestion.

Actions of Bitter Herbs

The choice of bitter herbs to enhance digestion can also be made based on the physiological systems that can be affected. Considering these additional actions of the bitter herbs can assist in differentiating and individuating the best choice for each patient.

Plants with bitter principles come in varying degrees of bitterness, which has been standardized by an organoleptic method, calculated by the concentration of crude herb dissolved in water where the bitter taste still remains, which is then given a value. The higher the value, the more intense the bitter (Sanberg and Corrigan, 2001).

Taking into consideration the degrees of bitterness, along with the understanding of the patient’s digestive function and other physiological actions of the plants, the most effective bitters can be chosen for each patient.

Accompanying this article is a list of bitter herbs from most intense to least intense, based on my interpretations of the literature and clinical experiences.

Use With Pregnancy

Although some herbal resources will state that the use of herbs as bitters in pregnancy and lactation is contraindicated, there is a range of opinions regarding their safety, and each herb should be evaluated individually. One reference to assist in critical thinking about the safety of herbs in pregnancy and lactation is the Mills and Bone book (2005; see References for details). In this book, the authors describe categories of safety rankings for herbs based on both traditional knowledge and current literature. Safety monographs are included for 135 herbs.

Based on the ranking system in the Mills and Bone reference text and my clinical experience and critical thinking, the accompanying list includes recommendations for which bitter herbs are contraindicated in pregnancy and which herbs may be safe enough to consider prescribing.

Other Contraindications

Other contraindications for the use of bitters are gallbladder disease with a bile obstruction and a hyperchlorhydric state. According to some sources, duodenal ulcers can be aggravated by the use of bitters, although some people with peptic ulcers may find that appropriate dosing of bitters can help to facilitate healing of the lesion (Toma, 2002). Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is often listed as a contraindication for the use of bitters. In some cases, GERD can be related to a hypochlorhydric state, and with careful monitoring, bitters may be useful in the healing of this reflux condition based on improvement of the tone of the esophageal sphincter and re-equilibration of the secretion of HCl when food is present rather than when it is not.

When indicated and in the proper dosing, along with making the best choice of herbs, bitters can be a useful tool in making the digestive system optimally well. As it is the seat of health and wellness, this will create optimal health in the patient overall.

Bitter Herbs, From Most Intense to Least Intense

The iridoid glycoside group represents the highest degree of bitter taste in the plant kingdom (Hoffman, 2003). These iridoids also bring antimicrobial action. The secoiridoid glycoside amarogentin in Gentiana lutea (gentian) has a bitterness value of 10 to 58 million (Samuelsson, 1999). Gentian could also be considered for its actions as a cholagogue and hepatic.

Equally bitter are the harpagosides in Harpagophytum procumbens (devil’s claw), which also support inflammation-modulating effects, and the verbenalin in Verbena officinalis (vervain), which acts as an antispasmodic and nervine.

Sesquiterpene lactones – for example, the absinthin found in Artemisia absinthium (wormwood), lactucin found in Lactuca virosa (wild lettuce) and achillin in Achillea millefolium (yarrow) – are the second most bitter of the plant compounds. Artemisia absinthium is an antimicrobial and vermifuge; Lactuca is one of the stronger sedatives in the herbal Materia Medica; and Achillea is an herb that has many actions, including antimicrobial, inflammation modulation, carminative and nervine. The diterpene lactone marrubiin in Marrubium vulgare (horehound) is also a very strong bitter, as well as acting as an antimicrobial, antispasmodic and expectorant, used in upper respiratory conditions with a cough.

Alkaloids yield a significant bitter taste, often warning the body of toxicity. The following two plants, high in alkaloids, are often included in the group of digestive bitters. Ruta graveolens (rue), with the alkaloids arborinine and graveoline, also acts as an antispasmodic and strong emmenagogue. Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal), with its alkaloids hydrastine and berberine, is known as an antimicrobial and inflammation modulator within the gut, healing the mucous membranes.

The remaining bitter herbs on the list are relatively mild bitters compared to those just discussed.

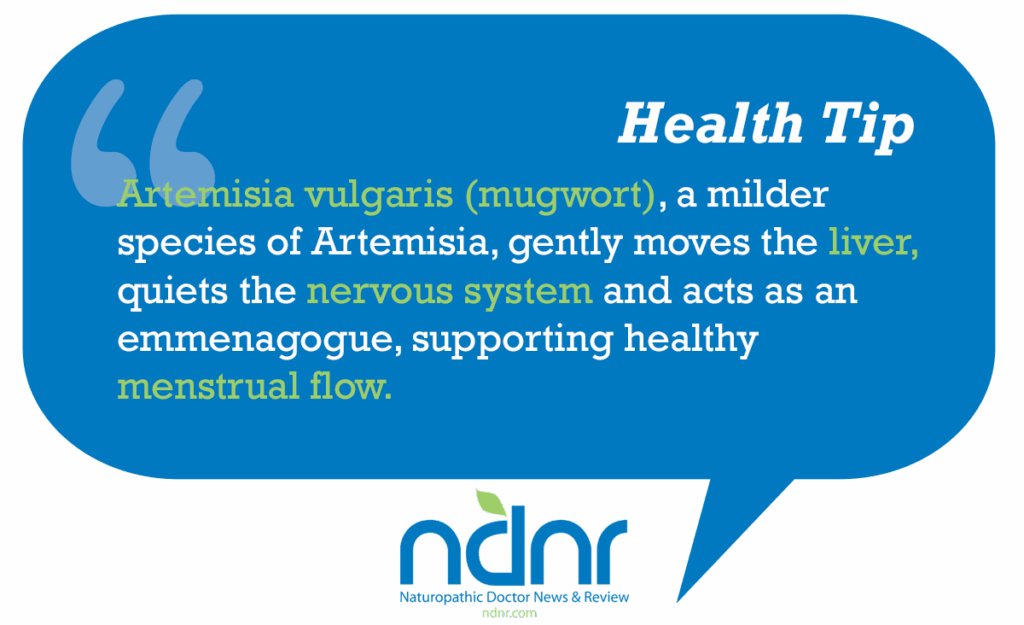

Agrimonia eupatoria (agrimony), one of the Bach Flower remedies, is high in tannins, giving it its astringent and inflammation modulating actions. Artemisia vulgaris (mugwort), a milder species of Artemisia, gently moves the liver, quiets the nervous system and acts as an emmenagogue, supporting healthy menstrual flow. Matricaria recutita, chamomile, is a carminative and nervine, easing digestive unrest, as well as being an inflammation modulator and vulnerary, healing gut tissue. Menyanthes (bogbean) has anthraquinone glycosides, and acts as a gentle laxative. Although it also contains iridoids, the bitterness value is 9,000, much lower than gentian. Iris veriscolor (blue flag), known for its work on conditions of the skin, acts as an alterative while modulating inflammation.

Herbs and Pregnancy

Herbs and Pregnancy

Artemisia absinthium, because of the alpha and beta thujone content, and Hydrastis canadensis, because of the alkaloids, are not recommended in pregnancy, although Hydrastis may be considered for short-term use in acute infections since it is poorly absorbed. Achillea millefolium and Marrubium vulgare show no harmful effects on human fetal development from limited use. Some animal studies have shown evidence of damage; therefore, these herbs are best avoided, especially in the first trimester and for use in an extended period of time. Gentiana lutea, Harpagophytum procumbens and Lactuca virosa show no harmful effects on human fetal development from limited use. However we don’t really know, so using them with caution or not at all would be suggested. Matricaria recutita and Iris versicolor are considered safe in pregnancy, showing no harmful effects.

Although these herbs discussed do not have monographs in the Mills and Bone reference text, their relative safety can be deduced. Menyanthes trifoliata and Verbena officinalis, because they both contain iridoid glycosides, would be grouped into the category with Gentiana, showing no harmful effects on human fetal development from limited use. Although Artemisia vulgaris is much milder than A. absinthium, it has been used traditionally as an emmenagogue, so it would be contraindicated. Ruta graveolens, with its abortifacient alkaloids arborinine and graveoline, is absolutely contraindicated. However, Agrimonia eupatoria, a member of the Rosaceae family, is a safe bitter in pregnancy. The tannins in Agrimonia can also enhance protection and support healing of the mucous membranes of the gut.

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH(AHG) earned her degree in naturopathic medicine from Bastyr University in 1995 where, following graduation, she became a member of the didactic and clinical faculty. For the past eight years, she has served at Bastyr as department chair of botanical medicine, teaching and administering to both the naturopathic medicine program and the bachelor’s of science in herbal sciences program. Dr. DiPasquale is a clinical associate professor in the department of biobehavioral nursing and health systems at the University of Washington in the CAM certificate program. She loves plants, is published nationally and internationally, and teaches throughout the U.S. and in Italy about plant medicine. She is an anusara influenced yoga teacher, teaching the flow of yoga from the heart. She currently has a general naturopathic medicine practice in Madison, Wis., and is working with the University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine Clinic as an ND consultant.

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH(AHG) earned her degree in naturopathic medicine from Bastyr University in 1995 where, following graduation, she became a member of the didactic and clinical faculty. For the past eight years, she has served at Bastyr as department chair of botanical medicine, teaching and administering to both the naturopathic medicine program and the bachelor’s of science in herbal sciences program. Dr. DiPasquale is a clinical associate professor in the department of biobehavioral nursing and health systems at the University of Washington in the CAM certificate program. She loves plants, is published nationally and internationally, and teaches throughout the U.S. and in Italy about plant medicine. She is an anusara influenced yoga teacher, teaching the flow of yoga from the heart. She currently has a general naturopathic medicine practice in Madison, Wis., and is working with the University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine Clinic as an ND consultant.

References

Frawley D and Lad V: The Yoga of Herbs. CITY, 1986, Lotus Press.

Hoffman D: Medical herbalism: the science and practice of herbal medicine. CITY, 2003, Healing Arts Press.

Mills S and Bone K: The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety. CITY, 2005, Elsevier Churchill Livingstone.

Samuelsson G: Drugs of Natural Origin (4th revised ed). CITY, 1999, Apotekarsocieteten (Swedish Pharmaceutical Society).

Sanberg F and Corrigan D: Natural Remedies: Their Origins & Uses. CITY, 2001, CRC Press.

Toma W et al: Antiulcerogenic activity of four extracts obtained from the bark wood of Quassia amara L. (Simaroubaceae), Biol Pharm Bull Sep;25(9):1151-5, 2002.