Joint Pain, Alcohol, & NSAIDs: Harnessing the Power of Our Plant Allies

Student Scholarship – 1st Place Case Study

KATIE COLEMAN

JENNIFER BRUSEWITZ, ND

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are one of the most commonly used drug classes worldwide for analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as for cardiovascular disease and cancer prevention.1 Categories of over-the-counter (OTC) NSAIDs include ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin. Ibuprofen is the most frequently used non-aspirin NSAID and one of the most commonly used drugs overall in the United States.2 However, long-term use of NSAIDs is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcers, bleeds, and perforations.3-5 NSAIDs weaken and irritate the intestinal mucosa by disrupting the lining’s protective mechanisms.6

When NSAIDs are used in conjunction with alcohol, especially in the amount of 3 or more alcoholic beverages per day, there is further increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.7 Alcohol alters intestinal microbiota in the gut and increases permeability of the intestinal mucosa, promoting dysbiosis and bacterial overgrowth; endotoxins are released that cause intestinal inflammation. Alcohol also disrupts the intestinal lining by directly injuring epithelial cells through oxidative stress, further damaging tight junctions and increasing inflammation. As well, alcohol may induce atrophic gastritis, which reduces absorptive capacity, leading to nutrient deficiencies.8 The life-threatening risks and side effects of long-term NSAID use, especially when used concurrently with alcohol, expose a need for nontoxic agents with similar therapeutic benefits. This article describes a naturopathic approach to treating chronic joint pain in a patient with a 30-year history of alcohol use as well as long-term, high-dose NSAID use for the joint pain.

Presenting Concerns & History

A 63-year-old male presented to the clinic with a 6-year history of severe, sharp, and constant bilateral knee pain and right shoulder pain. He was seeking natural treatments for his chronic pain. The pain resulted from multiple injuries, leading to a diagnosis of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. For pain management, the patient reported taking up to 2400 mg of OTC ibuprofen daily. His past medical history was significant for alcohol use, which began when he was a teenager and included frequent blackouts. He was participating in a rehabilitation program when he came to our clinic, and reported current abstinence from alcohol for 6 weeks.

Clinical Findings

Upon questioning, the patient reported recent normal lab testing – CBC, ferritin, CMP – which ruled out excessive liver inflammation and anemia. He denied symptoms of myalgias and paresthesias, and signs of anemia were absent. A musculoskeletal exam demonstrated good muscle tone and strength, as well as normal active, passive, and resisted ranges of motion in his knees bilaterally and in his right shoulder, with the exception of sharp pain elicited in his shoulder during flexion and abduction. We used a pain scale at each visit, asking the patient to rate his pain on a scale from 0 to 10 (with 10 as the highest) and later categorizing the pain as mild, moderate, or severe, to determine and track his pain levels.

His diet consisted of processed cold cereal, sandwiches, and frozen entrees, with snacks of bananas, yogurt, and granola. He reported drinking 3 cups of coffee and 150 ounces of water daily.

Therapeutic interventions

Our primary treatment goal was to achieve sufficient pain relief to enable a reduction in the patient’s daily amount of ibuprofen use. The patient’s use of 2400 mg OTC ibuprofen daily exceeded the maximum recommended daily dose of 1200 mg. He understood the risk factors associated with ibuprofen use and was interested in decreasing his dosage. A second treatment goal was to decrease whole-body inflammation and promote joint healing. In order to accomplish these goals, naturopathic fundamental principles were utilized, including identifying and treating causes of inflammation and preventing harmful effects of long-term, high-dose NSAID use.

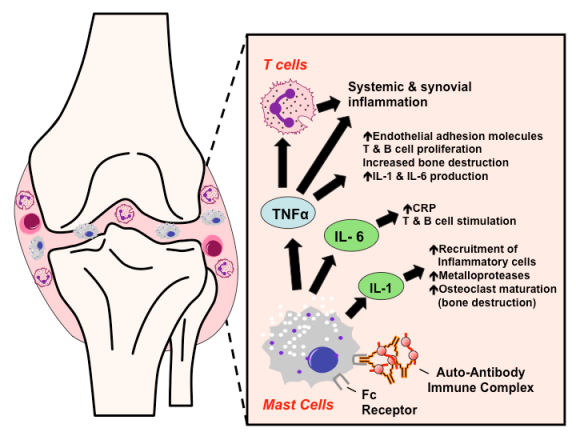

First, we addressed the patient’s daily pain due to osteoarthritis. This condition features destruction of articular cartilage, subchondral bone, and synovial membranes, which is promoted by inflammatory cytokines including interleukins (especially IL-1 and IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα).9 These cytokines contribute to damage of articular cartilage, predominantly by degrading proteins in the extracellular matrix and causing inflammation (see Figure 1). Medicinal plants inhibit inflammatory mediators and interact with cytokines, with a broader mechanism of action than that of NSAIDs. We looked into our bountiful herbarium to bring together the appropriate botanicals, in addition to some simple dietary recommendations, as a way to mediate cytokines to decrease pain and joint destruction and increase physical function.

Figure 1. Cytokines Involved in Joint Inflammation

(Image courtesy of Tulane University School of Medicine; Medical Pharmacology; TMedWeb23)

With the intent of reducing the patient’s ibuprofen use, we provided the patient with an herbal formula including ginger, curcumin, and Boswellia serrata, to be taken 2 times daily.

Ginger is a rhizome of Zingiber officinale and is well researched for its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. Gingerol is the major pungent compound of fresh ginger, and shogaol is the main pungent compound of dried ginger. Both of these compounds prevent inflammation by inhibiting the activity of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) converting enzyme, which is responsible for converting arachidonic acid into prostaglandin E2 and thromboxane.10,11 A study of patients with knee osteoarthritis, who were poor responders to NSAIDs, found that when given 25 mg of ginger with 5 mg of echinacea per day for 30 days, participants noticed significant improvement in pain and had measurable decreases in knee circumference related to inflammation.11 A meta-analysis of 5 studies examining oral supplementation of ginger for symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis demonstrated statistically significant reductions in pain and disability.12 Due to adequate and sustained pain relief, subjects given ginger were twice as likely to discontinue treatment of ginger supplementation, compared to subjects given a placebo.12

Curcumin, an active constituent of the rhizome Curcuma longa, is well known for its anti-inflammatory actions by modifying nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-ĸB) signaling, proinflammatory cytokine production, and COX-2 and 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) actions.13 The enzyme 5-LOX is responsible for the conversion of arachidonic acid into leukotrienes, which leads to an inflammatory response.11 Additionally, curcumin at doses of 1000 mg daily has been found to be effective and comparable in efficacy to ibuprofen for treating pain related to osteoarthritis.9

The gum resins of Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata) contain over 12 different boswellic acids, which are pentacyclic triterpenes that are known for their anti-inflammatory effects.14 Therapeutic actions of boswellic acids include decreasing inflammation and preventing the destruction of articular cartilage by inhibiting the production of leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and proinflammatory cytokines.14

In addition to our herbal combination, we asked the patient to take bromelain, a plant enzyme, to “digest” inflammatory compounds circulating in the body. Bromelain comes from pineapple and consists of protein-digesting enzymes, specifically thiol endopeptidases.15 Bromelain exhibits anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects by increasing serum fibrinolytic activity and reducing plasma fibrinogen and bradykinin levels.16 Doses of 500 mg bromelain per day have been found to be as effective at reducing symptoms of osteoarthritis after 4 weeks of treatment as 100 mg daily of the NSAID prescription, diclofenac.17

We also provided the patient with glucosamine sulfate at a dose 1.5-3 g per day, as he reported it worked well in the past at relieving his joint pain. Glucosamine is an amino sugar that comes from glucose and is a precursor to hyaluronic acid.18 By including glucosamine as a treatment for osteoarthritis, the body is provided with additional building blocks for joint structure and a possible delay in architectural joint damage.19

Finally, we encouraged the patient to adopt a Mediterranean-style diet by decreasing refined carbohydrate intake, specifically white sugar and processed grains, and increasing whole grains to reduce whole-body inflammation. The Mediterranean diet has been shown to ameliorate arthritis symptoms and improve quality of life in patients with osteoarthritis due to the diet’s well-researched anti-inflammatory effects.20

Follow-ups & Outcomes

Two Weeks

At the patient’s 2-week follow-up, he reported following our recommendations (with no adverse effects) and experiencing a noticeable reduction in knee and shoulder pain. His knee pain decreased from sharp, constant, severe pain bilaterally to dull, achy, moderate pain bilaterally. His right shoulder pain had decreased from constant, severe pain to intermittent, moderate pain, and now occurred only if he lifted his arm above 90 degrees. He was pleased to report that he had decreased his 600 mg ibuprofen dose from 3 times per day to once or twice per day.

At this visit, we recommended the patient start taking 1 tablet daily of a B-complex to replenish B vitamins, particularly thiamine, due to his history of long-term alcohol abuse. Thiamine deficiency, which can induce alcoholic peripheral neuropathy, is common in chronic alcoholism, since ethanol decreases thiamine absorption in the intestine, reduces its hepatic stores, and reduces its conversion to its active form.21

Four Weeks

At the patient’s 4-week follow-up, he reported slight improvement while following our recommendations. He stated that his knee pain was now an intermittent and moderate dull ache that would increase to severe, sharp pain only upon standing after long periods of sitting. Additionally, he reported that his morning knee pain had decreased from severe pain to moderate pain and was further relieved with movement and stretching. We recommended he apply topical capsicum/arnica cream to his knees and shoulder. Capsaicin is the neurotoxin in chili peppers that binds to the vanilloid compound receptor of type C afferent fibers and depletes neural substance P, leading to desensitization and analgesia.22 Capsaicin cream has been shown to be an effective symptom-reduction agent in osteoarthritis, as compared to placebo, and with a nontoxic safety profile.21 Finally, the patient noted his shoulder pain was present as a mild, dull ache only when his elbow was elevated above his shoulder. He continued to take 1-2 doses of 600 mg ibuprofen daily along with the previously prescribed supplements for pain management.

Six Weeks

At his 6-week follow-up visit, the patient reported continued improvement. He stated that his morning knee pain was now mild, as compared to severe pain 6 weeks prior, and that the pain decreased throughout the day. Additionally, he reported a reduction in frequency of sharp knee pain when transitioning from sitting to standing after long periods of sitting. The patient was delighted to tell us that his right shoulder pain had resolved and no longer woke him up at night. He reported using capsaicin cream for slow-acting pain relief. He informed us that he further reduced his ibuprofen intake to 600 mg once daily, with a second dose added every other night instead of nightly.

Discussion

NSAIDs are common medications used for pain relief, especially for pain management in osteoarthritis; however, serious life-threatening risks, including gastric ulcers and perforation, may result from long-term use of NSAIDs. The patient’s history of alcohol abuse while taking NSAIDs further compounded the need for a safe alternative to NSAIDs, to prevent potentially fatal side-effects of gastric bleeding. The positive analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of NSAIDs can be provided by botanicals such as ginger, curcumin, frankincense, bromelain, and capsaicin, and without negative side effects. By utilizing these powerful analgesic and anti-inflammatory herbs, we were able to modulate inflammation and support the patient in finding lasting pain relief for his osteoarthritis. Over a 6-week period, the patient accomplished the treatment goal of reducing ibuprofen intake (which he decreased by 50% after 3 years at a steady dose), and he is now enjoying the next chapter of his life with significantly less pain.

References:

- Davis JS, Lee HY, Kim J, et al. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in US adults: changes over time and by demographic. Open Heart. 2017;4(1):e000550.

- Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Battista DR, et al. Exceeding the daily dosing limit of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs among ibuprofen users. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(3):322-331.

- Ofman JJ, MacLean CH, Straus WL, et al. A metaanalysis of severe upper gastrointestinal complications of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(4):804-812.

- Griffin MR, Yared A, Ray WA. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and acute renal failure in elderly persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(5):488-496.

- He J, Whelton PK, Vu B, Klag MJ. Aspirin and risk of hemorrhagic stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1930-1935.

- Bishehsari F, Magno E, Swanson G, et al. Alcohol and Gut-Derived Inflammation. Alcohol Res. 2017;38(2):163-171.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. The benefits and risks of pain relievers Q&A with Sharon Hertz, M.D. September 24, 2015. FDA Web site. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/benefits-and-risks-pain-relievers-q-nsaids-sharon-hertz-md. Accessed October 27, 2019.

- Bujanda L. The effects of alcohol consumption upon the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(12):3374-3382.

- Cameron M, Chrubasik S. Oral herbal therapies for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(5):CD002947.

- Semwal RB, Semwal DK, Combrinck S, Viljoen AM. Gingerols and shogaols: Important nutraceutical principles from ginger. Phytochemistry. 2015;117:554-568.

- Rondanelli M, Riva A, Morazzoni P, et al. The effect and safety of highly standardized Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and Echinacea (Echinacea angustifolia) extract supplementation on inflammation and chronic pain in NSAIDs poor responders. A pilot study in subjects with knee arthrosis. Nat Prod Res. 2017;31(11):1309-1313.

- Bartels EM, Folmer VN, Bliddal H, et al. Efficacy and safety of ginger in osteoarthritis patients: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(1):13-21.

- Daily JW, Yang M, Park S. Efficacy of Turmeric Extracts and Curcumin for Alleviating the Symptoms of Joint Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J Med Food. 2016;19(8):717-729.

- Ammon HP. Boswellic Acids and Their Role in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;928:291-327.

- Pavan R, Jain S, Shraddha, Kumar A. Properties and therapeutic application of bromelain: a review. Biotechnol Res Int. 2012;2012:976203.

- Brien S, Lewith G, Walker A, et al. Bromelain as a Treatment for Osteoarthritis: a Review of Clinical Studies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1(3):251-257.

- Kasemsuk T, Saengpetch N, Sibmooh N, Unchern S. Improved WOMAC score following 16-week treatment with bromelain for knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(10):2531-2540.

- Bolognesi G, Belcaro G, Feragalli B, et al. Movardol® (N-acetylglucosamine, Boswellia serrata, ginger) supplementation in the management of knee osteoarthritis: preliminary results from a 6-month registry study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(24):5198-5204.

- Bruyère O, Altman RD, Reginster JY. Efficacy and safety of glucosamine sulfate in the management of osteoarthritis: Evidence from real-life setting trials and surveys. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(4 Suppl):S12-S17.

- Morales-Ivorra I, Romera-Baures M, Roman-Viñas B, Serra-Majem L. Osteoarthritis and the Mediterranean Diet: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2018;10(8). pii: E1030. doi: 10.3390/nu10081030.

- Chopra K, Tiwari V. Alcoholic neuropathy: possible mechanisms and future treatment possibilities. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(3):348-362.

- Guedes V, Castro JP, Brito I. Topical capsaicin for pain in osteoarthritis: A literature review. Reumatol Clin. 2018;14(1):40-45.

- Tulane University, School of Medicine. Medical Pharmacology; TMedWeb; PharmWiki. Rheumatoid Arthritis. Last modified March 14, 2019. Available at: http://tmedweb.tulane.edu/pharmwiki/doku.php/rheumatoid_arthritis. Accessed October 27, 2019.

Katie Coleman is a naturopathic doctoral student completing her final year at the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM). Prior to attending NUNM, Katie studied animal science and management at the University of California, Davis. She has a passion for gastroenterology and vitalism and is a proud member of GastroANP and the Naturopathic Medicine Institute.

***

Jennifer Brusewitz, ND, graduated from the National University of Natural Medicine. She currently practices in Portland, OR, and serves as academic faculty at NUNM and as a clinical supervisor at NUNM’s teaching clinics. She also investigates and implements quality assurance standards for the university’s dispensary.