Naturopathic Support for an Individual with a Stoma: Case Study of an 84-Year-Old Woman with a Transverse Colostomy Resulting from Acute Intestinal Infarct

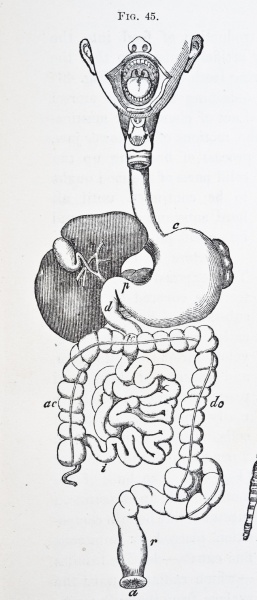

The word stoma comes from the Greek for “mouth” or “opening.” A stoma is a surgically created opening in the abdomen through which feces or urine is directed outside of the body. The surgical procedure, called an ostomy, may be required for various disorders (Table 1) that impair the function of the bowel or bladder.1 A colostomy is the most frequently performed ostomy,2 whereby the opening is fashioned into the colon (Figure).

There are more than 1 million persons in the United States and Canada living with intestinal stomas, and it is estimated that 100 000 ostomy surgical procedures are performed each year.3 Approximately 65% of these individuals have a permanent stoma.1 Ostomies tend to be more common in older populations because contributing illnesses such as colorectal cancer and diverticular disease have a higher incidence in this age group. As our society ages, the number of patients with a stoma will likely increase.1

Naturopathic medicine is adept at treating chronic health conditions. Because many of the conditions leading to ostomies are of a chronic nature, it is likely that today’s ND can expect to treat patients with these unique needs sometime in the course of his or her clinical career. Dietary consultation, emotional support, and stress management are just a few of the wellness issues encountered by a patient with an ostomy in which NDs are uniquely qualified to help. Naturopathic physicians can have a valuable role in the interdisciplinary healthcare team of a patient with an ostomy.

Case History

Mrs L had presented to the emergency department with severe periumbilical pain and a history of constipation. Her abdomen was soft and nontender on examination. Fecal impaction was the initial working diagnosis; however, 2 enemas performed in the emergency department provided no benefit. Surgical and gastroenterological referrals were made. On further testing, the working diagnosis was modified to mesenteric ischemia. Medical treatment included bowel rest, anticoagulation, intravenous fluid replacement, morphine sulfate, and broad-spectrum antibiotics.

In-hospital medical treatment continued for approximately 1 month, at which time examination revealed absent bowel sounds and abdominal rigidity. Bowel infarction had occurred, and sepsis was imminent. Emergency exploratory laparotomy and subsequent transverse colostomy were performed. Mrs L remained in intensive care following the surgery for 2 weeks. She was ultimately discharged from the hospital to return home approximately 6 months later. Being bedridden for so long had caused Mrs L to lose function in her legs. Several months of rehabilitation were required to enable her to return to walking with a cane.

Mrs L was 84 years old at the time of her surgery. She has a history of asthma, osteoarthritis, breast cancer for which lumpectomy was performed, thyroid cancer for which thyroidectomy was performed, and absence seizures. Phenytoin was the only medication she was taking before entering the hospital. She had never smoked or used oral contraceptives, does not consume alcohol, and is healthy and of normal weight. She had no history of atherosclerosis, deep vein thrombosis, or cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease.

Several days before her emergency ostomy, I was asked by Mrs L’s family to provide naturopathic care. Table 2 gives an overview of the naturopathic support provided.

Key naturopathic interventions included adding additional glutamine to Mrs L’s parenteral nutrition. Glutamine is beneficial for repair of intestinal tissue, ensuring normal permeability of the intestines. It also helps to prevent villus atrophy in the small intestine.4 A modified form of constitutional hydrotherapy was performed on a daily basis to gently stimulate the healing process, to aid detoxification, and to relieve stress on the digestive system. Castor oil packs over Mrs L’s entire abdomen were applied approximately 3 times per week to also aid detoxification and to support digestion.

Acupressure was initially performed on a daily basis to relieve obstructed or stagnant qi within the intestines. Points were modified throughout the process to address emotional concerns such as Mrs L’s grief over her loss of independence and to help strengthen her lower limbs. Massage and touch therapy were performed at the end of acupressure sessions to stimulate blood and lymphatic circulation.

Once out of the hospital, Mrs L was advised to supplement her diet with a high-quality multivitamin to help replenish nutritional deficiencies, along with fish oil for its anti-inflammatory properties and probiotics to replace beneficial bacteria lost because of antibiotics use. She was also given an herbal tincture that had bitter, nervine, anti-inflammatory, alterative, and hepatic properties.

Laboratory test results continue to be monitored at regular intervals. These include serum urea, creatinine, sodium, potassium, magnesium, and C-reactive protein levels.

Considering her age and other complicating factors (Table 3), a “wait and watch” approach was originally adopted for Mrs L because her physicians doubted that she would survive surgery. Unfortunately, her condition deteriorated to the point where life-saving surgery was required. The average mortality rate for acute mesenteric ischemia is 71% and is even higher when bowel infarction is a complication.5 Although gravely ill, Mrs L was able to beat the odds, thanks to the dedicated support of her family, the skill of her healthcare team, and, perhaps most important, her unwavering determination to get better.

Unique Needs of an Individual With a Stoma

Nutrition

Older persons have unique nutritional needs such as increased risk of malnutrition, and those who have a stoma, like Mrs L, often have additional concerns. Individuals with colostomies generally do not have any dietary restrictions; however, older persons with colostomies may be prone to dehydration and constipation.

Water is absorbed throughout the colon, but because there is less bowel available in the case of a colostomy, less water will be absorbed. In addition, some older persons may be reluctant to drink adequate amounts of liquids for fear of increased urinary frequency and problems in mobilizing to the bathroom.6 By the time Mrs L was discharged, this was not a concern, and she was advised to drink at least 1½ L of water each day to help prevent dehydration.

Analgesics containing codeine phosphate can slow down peristalsis in the gut, resulting in hard constipated stools. Fortunately, Mrs L did not require painkillers by the time she returned home. To prevent constipation, she was advised to increase her fiber intake by consuming more vegetables. Foods high in fiber can increase flatus; however, Mrs L agreed that the benefits outweigh the inconvenience of having to empty, or “burb,” her colostomy appliance more often. She was also advised to reduce her intake of dairy products and wheat and to maintain adequate daily physical activity.

The bulk of sodium absorption takes place in the ascending colon, left intact in Mrs L’s case, so risk of sodium depletion is generally not as great in a colostomy as in an ileostomy.7 Regardless, Mrs L was educated about symptoms of dehydration such as thirst, dizziness, headaches, and lethargy and was advised to eat a salty snack such as pretzels and to consume more water (avoiding dehydrating fluids that contain alcohol or caffeine) if she experienced such symptoms. She was also advised to consume foods high in potassium such as Swiss chard, yams, avocado, spinach, papaya, and lentils to maintain her balance of sodium to potassium.

Nutritionally, most of our general naturopathic recommendations apply and are beneficial to patients with a stoma. These include chewing food thoroughly to aid digestion, eating a well-balanced diet high in fruits and vegetables, ensuring adequate hydration, consuming healthy protein with each meal, incorporating healthy fats such as olive oil and flaxseed oil into the diet, and avoiding refined carbohydrates and substances associated with food sensitivities.

Physical Complications

Retrospective investigations indicate that approximately 34% of patients with a stoma have complications after surgery, 28% of which occur in the first postoperative month.7 Mrs L has experienced 2 such complications, parastomal herniation and peristomal dermatitis.

Most commonly seen with colostomies, parastomal hernias occur when a loop of herniated bowel pushes through a defect in the fascia of the abdominal wall, creating bulging of the peristomal skin. They can occur in up to 50% of patients with a stoma. Parastomal hernias can be unsightly under clothing for the patient and may make it difficult to properly fit appliances. Because parastomal hernias are rarely life threatening, surgery is avoided whenever possible.8

Mrs L lives with the parastomal herniation, using a support belt during her waking hours to help prevent the herniation from increasing in size. The herniation is nonsymptomatic, but she is monitored for signs of prolapse, stenosis, pain, or any difficulty in emptying bowel contents. Calcarea fluorica tissue salt was recommended to address the lack of connective tissue elasticity in her abdominal wall and to prevent further herniation or prolapse.

Leakage of feces onto the skin can cause erosion due to its alkalinity relative to the slightly acidic state of our skin.3 Mrs L experienced fecal contact and allergic contact peristomal dermatitis because of her sensitivity to various adhesives. A hypoallergenic adhesive was chosen, and Mrs L’s appliance was changed to better fit her stoma and herniation. A homeopathic cream (Table 2) was applied to her peristomal skin each time Mrs L’s appliance was changed (approximately every 4-6 days).

Other common complications can occur in patients with a stoma. These are summarized in Table 4.

Emotional Complications

Stoma formation may affect an individual not only physically but also psychologically. The following 3 main themes have emerged through qualitative research: (1) loss of embodied wholeness in which there may be a negative focus on the body or a sense of alienation from the body; (2) awareness of a disruption in the body in appearance, function, and sensation; and (3) disrupted bodily confidence, whereby the individual has less confidence in facing the world and in relationships.9 Table 5 summarizes emotional themes that an individual with a stoma may experience.

The theme of bodily restraints was a concern for Mrs L. She felt limited by her ostomy and feared its leaking or producing an odor while out in public. She was afraid of her bag’s bursting or breaking while in a place where she did not have immediate access to a bathroom. Order and cleanliness are of uppermost importance to Mrs L, and she often would not feel comfortable using a bathroom outside of her own home to empty or clean her bag.

In many ways, Mrs L has had to reconcile herself to a changed life. She has had to make a lot of adaptations and to overcome feelings of being “less whole,” infirm, and unable to manage everything she once could. In fact, she is now doing more than she did before the surgery. She loves to cook and bake and enjoys visiting with her family and friends. Her home is her castle, and she takes great pride in taking care of it. It took time to reach the point of acceptance and in certain ways remains an ongoing process for Mrs L. Although there have been restraints and obstacles, the practical side of Mrs L understands that her ostomy has allowed her to live.

In older individuals, it may be beneficial to think about the developmental stages by Erikson to help identify if an emotional crisis may be occurring.2 In later stages of life, “ego integrity versus despair” may be the main theme, whereby individuals stop participating in their daily life and develop feelings of anger and shame as a result of needing to be more dependent on others. Aspects of this were evident in Mrs L, especially her battling with being less independent. To help her cope, she was encouraged to engage in activities that bring her the most joy. Through counseling, she was aided to identify and focus on the positives in her life. Family support and therapy have been integral. Energetic therapies such as Bach flower remedies, acupuncture, and homeopathy were also beneficial in supporting Mrs L through emotional crises.

Conclusions

I learned a great deal from Mrs L and am grateful for the opportunity to have a small part in her health journey. Mrs L’s case helps illustrate the unique needs of patients with a stoma and the health challenges they face after surgery. As our population ages, we as primary care practitioners are likely to have contact with at least 1 patient with a stoma during our careers, and we as NDs have the proper skills and knowledge to provide beneficial dietary advice, required supplementation, and emotional support. Therefore, it is important that NDs become educated about how we can be of service to individuals with a stoma.

Dr. Candice Esposito, ND is a graduate of the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine. She is the founder of Algoma Natural Healing Clinic, located in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, where she enjoys serving her community, learning from her patients and educating the public about naturopathic medicine.

References

1. Black P. Teaching stoma patients the practical skills for self care. Br J Healthcare Assistants. 2010;4(3):132-135.

2. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. Ostomy care & management. 2009. http://www.rnao.org/Page.asp?PageID=122&ContentID=3012. Accessed November 11, 2010.

3. Agarwal S, Ehrlich A. Stoma dermatitis: prevalent but often overlooked. Dermatitis. 2010;21(3):138-147.

4. Marz RB. Medical Nutrition From Marz. 2nd ed. Portland, OR: Omni-Press; 2002.

5. Arnell T, Lee L, Mueller DK. Acute mesenteric ischemia: first consult. http://www.mdconsult.com. Accessed November 11, 2010.

6. Burch J. Dietary considerations for the older ostomate. Nurs Residential Care. 2006;8(8):354-357.

7. Fulham J. Providing dietary advice for the individual with a stoma. Br J Nurs. 2008;17(2):S22-S27.

8. Black P. Managing physical postoperative stoma complications. Br J Nurs. 2009;18(17):S4-S10.

9. Thorpe G, McArthur M, Richardson B. Bodily change following faecal stoma formation: qualitative interpretive synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(9):1778-1789.