Managing Stress & Mood Disorders

ALYSSA DIRIENZO, ND

Stress and anxiety are ubiquitous these days. Especially now – with the copious stressors associated with this pandemic, such as job loss, working from home, home-schooling, and now racial injustice as well – we need to be well versed in therapeutic options for addressing mental-emotional imbalances and underlying adrenal disorders from chronic stress. In my practice, a majority of patients report some degree of depressive or anxiety symptoms. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) can be used successfully as monotherapy, not just as adjunct to conventional medicine options. Additionally, patients who have mental and emotional disturbances often also display signs and symptoms of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction or adrenal dysfunction but don’t demonstrate the clinical criteria required for a conventional diagnosis.

A Delicate Balance

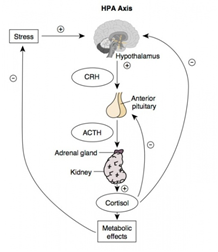

The HPA axis is part of the neuroendocrine system and controls our responses to stress. It also regulates bodily processes such as digestion, immune function, mood, sexual response, and energy storage and utilization. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), prolactin, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and growth hormone all originate from the anterior pituitary. Further up the chain, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is released from the hypothalamus following a stressor. Even outside of a true endocrine pathology, we can see disturbances in these hormones, as well as in neurotransmitters, as a result of mental-emotional and lifestyle stress and inflammation.

Upon receiving information in the hypothalamus, neurons release hormonal signals that elicit autonomic, hormonal, metabolic, and behavioral changes that are in direct response to the physical and emotional events we experience. These neuronal and hormonal pathways represent the connectivity between perception and response – in essence, what connects the inside and the outside. While most of what happens in the HPA axis is automatic, our awareness of the physiologic stress response creates a window of opportunity to modify our responses.

The HPA is at the heart of the body’s ability to respond to the environment. See Figure 1 for an overview of the HPA axis. Cortisol elevation is the result of CRH arising from the parvocellular neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN).1 CRH is the “master” stress hormone, released in response to our perception of stress. As we all know, stressful stimuli can be generalized as physical (eg, pain, infection, trauma, exercise, hypotension, or hypoglycemia) or as psychological (eg, fear, grief, or anger). Following a stressor, CRH is released from the hypothalamus and carried in the portal circulation by venous blood to the anterior pituitary where it binds to cell surface receptors; the pituitary responds by releasing ACTH. Subsequently, ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce cortisol and the androgenic hormones, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione.

Figure 1. HPA Axis

As the concentration of cortisol rises, it exerts negative feedback on the pituitary. This prevents prolonged elevations of CRH, ACTH, and cortisol. Chronic stress and maladapted responses to it can result in long-term dysregulation in this system and even cortisol resistance.2 This alteration in normal action as a result of chronic stress is something we see in so many of our patients. Robert Sapolsky, a professor of neurology and neurosurgery at Stanford, describes this human maladaptation in his book, Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers.3 Sapolsky conveys the concept that humans uniquely activate the stress response for psychological reasons, even without an observable stressor. This allows humans to continually activate the stress response, causing physiologic harm.

Stress Effects on the Body

Another major contributor to our understanding of the stress response is Hans Selye. As a pioneering endocrinologist, he found that ongoing stress could lead to illness. In his experiments with rats, in which he injected one group with ovarian extract, and injected a placebo group with saline, he found that even the placebo group experienced diminished immune tissues, ulcers and enlarged adrenal glands.4 He realized that any injection, even with a benign substance, caused harm thru stress. Selye defined 3 stages of the stress response: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion. He also distinguished “eustress” as a modest-level stressor that is actually necessary in order to feel engaged, capable, and satisfied. Through his work, he determined the timing of when illness occurs in the stress response. Specifically, he found that it was not in the exhaustion phase, but rather during prolonged time in the first 2 stages – alarm and resistance – that leads to damage in those processes that help maintain health.4

For stress recovery and mental-emotional well-being, we must work to maintain a balanced HPA response to stress. With other hormonal imbalances, such as in hypothyroidism or menopause, mere replacement of hormones is often ineffective at producing a sufficient resolution of symptoms. With both thyroid- and sex hormone replacement, it is imperative to also restore adrenal health. The list of possible symptoms of adrenal dysfunction is long. Symptoms of fatigue, anxiety, and depression are common, but other symptoms can also be present, such as sleep disruption, alcohol intolerance, and even eosinophilia with periodic or recurrent hives, which I’ve observed in some of my patients who also have an abnormal adrenal panel.

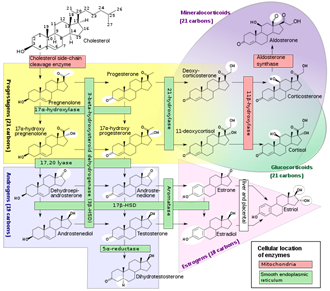

Figure 2 illustrates the cascade of hormones originating from cholesterol.2 DHEA is a precursor to male and female sex hormones. The average daily production of DHEA in men is around 31 mg and in women is around 19 mg.5 Most of DHEA, whose half-life is 15-38 minutes,6 is conjugated to sulfate to produce DHEA-S prior to being released into the circulation. The average daily production of DHEA and DHEA-S both show age-related, progressive decline, which results in approximately 80% reduction of normal levels by the seventh decade of life.7,8

For serum evaluation, DHEA-S is the preferred test. Unlike DHEA, cortisol levels vary significantly throughout the day. Since a serum test is only indicative of the level at the time of the blood draw, it is advantageous to evaluate cortisol with a serial salivary sample collection over the course of a day in order to get a more complete picture. Additional testing that is important to consider for a thorough evaluation of patients with health concerns – especially those suffering with chronic stress – includes: thyroid function testing, fasting insulin, fasting glucose, HgA1c, a lipid panel, hsCRP, and homocysteine.

Figure 2. Steroid Hormone Cascade

Approach to the Patient

Workup

Considering mood implications of chronic stress, the first step in addressing patients with suspected depression or anxiety is a thorough assessment. I believe it is paramount to utilize objective tools for both initial assessment as well as monitoring efficacy of treatment. A variety of questionnaires are available that practitioners can easily implement in practice with patients. Examples include the Hamilton Depression scale, BECK Inventory, Burn’s Assessment, and the PHQ-9. A thorough assessment should also include the evaluation of thyroid function, vitamin D status, CBC, and ferritin, as well as genetic polymorphisms in: MTHFR, CBS, and COMT genes. The various neurotransmitters to consider in patients with chronic stress are not only serotonin, but also catecholamines, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and endorphins. These neurotransmitters all have nutrient precursors, and considering the features of each of these neurotransmitters can help guide treatment options for nutrient support. Endorphins are phenylalanine dependent, and sufficient amounts allow one to feel comfort, pleasure, and euphoria. GABA is used as the main inhibitory neurotransmitter, and ample concentrations allow a person to feel calm and focused. Tyrosine-dependent catecholamines include: dopamine, norepinephrine, and adrenaline; catecholamines largely contribute to feeling energized, upbeat, and alert.

Treatment

Following a workup that evaluates underlying physiologic etiologies, support of patients with mood disorders should be comprehensive, including diet, lifestyle, and nutrient and/or herbal recommendations. For patients with depression and/or anxiety, dietary recommendations are integral to successful treatment. In addition to ensuring a balance of quality protein, fat, and carbohydrates, antioxidant-rich diets have been shown to correlate with lower prevalence and severity of depression.9,10

In addition to commonly used CAM agents for depression, such as Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) and omega-3 fatty acids, supporting serotonin production with 5-HTP, zinc, and vitamins B6, B12, and folate can be extremely beneficial. The compound 5-HTP is an intermediate metabolite in the synthesis of serotonin from tryptophan. Unlike tryptophan, 5-HTP does not get shunted into the production of other nutrients. It is also highly absorbable when taken orally, and can ameliorate not only depression, but also sleep disruption.11 Folate has long been utilized conventionally as an adjunct to antidepressant therapy. Considering that folate, B6, and B12 are all essential for the conversion from 5-HTP to serotonin, a complete treatment should include supplementation of all 3 of these B vitamins. Another integral nutrient in depression treatment is zinc. As zinc is not highly concentrated in many foods, patients are often zinc deficient, even with a relatively good diet. There is good evidence for zinc as a successful adjunct to antidepressant therapy, even in resistant cases.12

As the main inhibitory neurotransmitter, supplementing GABA is a mainstay of treatment for anxiety. Although GABA is able to cross the blood-brain barrier, its efficacy is best demonstrated long-term as the levels become “re-stocked.” The amino acid L-theanine helps boost GABA and may also increase dopamine. Piper methysticum (kava), a well-known anxiolytic herb, can be beneficial acutely by itself or in addition to other herbs, such as Humulus lupulus (hops) and Passiflora incarnata (passionflower).13 Outside of specific anxiolytic agents, is can be helpful to replete integral nutrients that help tonify the nervous system, including inositol, calcium, and magnesium.

For support of the HPA and adrenal function in patients with chronic stress, my favorite botanical adaptogens include: Rhodiola, Eleutherococcus senticosus, and Withania somnifera (ashwagandha). Rhodiola has also been shown to support healthy neurotransmitter levels.14 As adaptogens, these herbs neither overtly stimulate nor suppress adrenal function or hormone production; rather, they act as balancing agents. Eleutherococcus has long been used for adrenal complaints as well as other hormonal imbalances, and has also been shown to enhance memory function.15 Ashwagandha can help support hormonal balance, stabilize mood, and restore sexual function.16,17 Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) can also be utilized in chronic stress, especially in patients with diminished cortisol levels. Although many people have a misconception that licorice acts like cortisol, the role of licorice in HPA dysfunction is in reducing the degradation of cortisol and therefore helping to maintain cortisol levels when necessary. DHEA should be replaced when insufficient. Overall, DHEA can be described as an anti-stress hormone that also enhances immune function by directly stimulating T-lymphocytes.18

Closing Comments

Adrenals fare best with consistency in all things, eg, maintaining consistent mealtimes and sleep and wake times, keeping blood sugar stable, and engaging in restorative practices that allow for a decreased stress response. Many different factors can activate a disrupted stress response. As we work with our patients with hormonal and mental-emotional issues, it is of paramount importance to address the HPA axis.

References:

- Aguilera G, Liu Y. The molecular physiology of CRH neurons. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33(1):67-84.

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Doyle WJ, et al. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(16):5995-5999.

- Sapolsky R. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Henry Holt & Co.; 2004.

- Selye H. The Stress of Life. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 1978.

- Stengler M. Nature’s Virus Killers. New York, NY: M. Evans & Company; 2001.

- Pepping J. DHEA: dehydroepiandrosterone. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57(22):2048-2056.

- Warner M, Gustafsson JA. DHEA – a precursor of ERβ ligands. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;145:245-247.

- Dharia S, Parker CR Jr. Adrenal androgens and aging. Semin Reprod Med. 2004;22(4):361-368.

- de Oliveira NG, Teixeira IT, Theodoro H, Branco CS. Dietary total antioxidant capacity as a preventive factor against depression in climacteric women. Dement Neuropsychol. 2019;13(3):305-311.

- Abshirini M, Siassi F, Koohdani F, et al. Dietary total antioxidant capacity is inversely associated with depression, anxiety and some oxidative stress biomarkers in postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2019;18:3.

- Birdsall TC. 5-Hydroxytryptophan: a clinically-effective serotonin precursor. Altern Med Rev. 1998;3(4):271-280.

- Szewczyk B, Szopa A, Serefko A, et al. The role of magnesium and zinc in depression: similarities and differences. Magnes Res. 2018;31(3):78-89.

- Lakhan SE, Vieira KF. Nutritional and herbal supplements for anxiety and anxiety-related disorders: systematic review. Nutr J. 2010;9:42.

- Chen QG, Zeng YS, Qu ZQ, et al. The effects of Rhodiola rosea extract on 5-HT level, cell proliferation and quantity of neurons at cerebral hippocampus of depressive rats. Phytomedicine. 2009;16(9):830-838.

- Yamauchi Y, Ge YW, Yoshimatsu K, et al. Memory Enhancement by Oral Administration of Extract of Eleutherococcus senticosus Leaves and Active Compounds Transferred in the Brain. Nutrients. 2019;11(5):1142.

- Chandrasekhar K, Kapoor J, Anishetty S. A prospective, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study of safety and efficacy of a high-concentration full-spectrum extract of ashwagandha root in reducing stress and anxiety in adults. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(3):255-262.

- Dongre S, Langade D, Bhattacharyya S. Efficacy and Safety of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) Root Extract in Improving Sexual Function in Women: A Pilot Study. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:284154.

- Boudarene M, Legros JJ, Timsit-Berthier M. Study of the stress response: role of anxiety, cortisol and DHEAs. Encephale. 2002;28(2):139-146. [Article in French]

Alyssa DiRienzo, ND, is a 1999 graduate of the National University of Naturopathic Medicine (NUNM) in Portland, OR, where she also completed a residency in general family medicine. Additionally, she pursued a year of post-doctoral study in women’s health through the Institute of Women’s Health and Integrative Medicine. Dr DiRienzo served as adjunct clinical faculty for Bastyr for 10 years, and currently has a private practice, Sage Medicine, in North Bend, WA.