The Cast of Characters: Combating Childhood Anxiety From a Biopsychosocial Perspective

NICOLE CAIN, ND, MA

Esme is a good case example of an anxious child. Her first panic attack resulted in her losing consciousness during music class. During the second attack, she felt dizzy and nauseated, and then she missed the rest of the school day. After the third attack, Esme refused to return to 6th grade.

She had missed an entire semester of school. Because of her anxiety, the family was exploring Esme’s eligibility for an Individualized Education Program (IEP).

Music class was Esme’s favorite part of the day. On the day of that first panic attack, the students were singing a song, when, all of a sudden, a boy named Bobby became violently ill and began vomiting. Esme was in close proximity to him and could see and smell the vomit, and became extremely ill herself. She was sent home, and wound up missing several days of school due to an upset stomach.

The following week, when the class resumed in the music room, the students were standing and doing their vocal warm-ups and Esme was seized with extreme anxiety and lost consciousness. By the third week, Esme was already anxiously anticipating going to school, with the feelings manifesting as pain and queasiness in her gut. She reported that she couldn’t get the image of Bobby vomiting out of her mind and that she was terrified of getting sick or passing out again. After the same thing happened in the fourth week, Esme had made her decision.

While part of Esme desperately loved school, and part of her wanted to return, every time she thought about going back, the panic and anxiety reappeared. She had decided to stay home, and no matter what her parents said, the fear was too strong for her mind to change.

The Biopsychosocial Model of Care

Prior to 1977, the dominant model for understanding both biological and psychological disease was biomedical. While the biomedical model offers a foundation for therapeutic understanding of the cause of illnesses, its major limitation is that it neglects to consider variables beyond biological abnormalities. In response to this, in 1977, George L. Engel developed what he called the “biopsychosocial model.”1 This new model expanded on the original biomedical model for understanding illness by including psychological and social factors. Since this time, biopsychosocial methodologies have emerged as the most dominant integrative approach in clinical psychology.1

Meanwhile, I created what I call the “Cast of Characters.” This concept improves on the understanding of the original biopsychosocial model by incorporating, in a multidisciplinary fashion, advancements in psychological principles of trauma-informed care.2 I have updated the language to make it accessible to the consumer, and have provided exercises for exploring these health factors.

The Cast of Characters in Children’s Anxiety

The name “Cast of Characters” plays on literary terms to illuminate the different elements that impact a person’s physical and emotional health. The presupposition is that a person’s life is both directly and indirectly impacted by internal and external influences, and a new organizational structure is proposed for purposes of explanation to the client.

The Cast of Characters is comprised of:

- Psychological Characters

- Social Characters

- Physical Characters

Psychological Characters

Psychological Characters goes beyond the basic psychological tenet of the biopsychosocial model by acknowledging that there are many aspects to a person’s mental and emotional self.

Have you ever felt conflicted about something? It could be something small, like: Do I want a salad or a sandwich for lunch? Or, it could be something much more important, like: Do I get on this airplane, or is my anxiety accurate in telling me it’s too dangerous? This lack of certainty can be an incredibly stressful experience for anyone, especially a child.

Developmentally, children do not possess the complex thinking that comes from a fully developed prefrontal cortex. In fact, the prefrontal cortex does not fully develop until approximately 25 years of age.3 As a result, children perceive things as black and white, or all or nothing. This is called concrete thinking, or literal thinking, and it does not leave room for thoughts and feelings that do not align.4

The confusion that arises from a lack of integration in one’s thoughts, feelings, and desires may result in confusion and insecurity. By helping the child to understand that it’s okay for them to feel different ways at the same time and to explore why they may be experiencing those conflicting feelings, we can start to untangle the web that underpins feelings of anxiety and panic.

For purposes of this article, we will focus on a therapeutic framework that I created. It is called the “4-Part P.A.R.T. Process,” and it is based on an evidence-based process called “Parts Work.”

Parts Work is used in Ego State therapy,5 Internal Family Systems (IFS),6 and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR),7 and asserts that the mind is made up of multiple parts, each with its own viewpoints and qualities.

The 4-Part PART Process

- P: Problem Identification

- A: Access The Deeper Message

- R: Retrieve Memories

- T: Tend to the Triggered Part

The following is an example of a typical process. First, you will see a description of how to do the step, and then you will see Esme’s experience when we did this exercise together.

P: Problem

Ask the children what is bothering them that they would like to work on. Maybe it’s a feeling, like being frustrated or worried. Or perhaps it is a sensation, like an elephant on their chest, or stomach upset, or even pains in their legs. Or maybe it’s an event that is outside of them, but they still feel mentally stressed and upset about it.

Whatever it is that they want to work on, instruct them to start by simply noticing. They may multi-task while doing this exercise. I often find that coloring or going for a walk is a helpful way to soothe children’s stress while doing Parts Work with them.

Here is what Esme described when I asked her what she noticed: “I’m too scared to go to school. When Bobby threw up, I could smell it and I thought I was going to get sick, too. I felt sad for Bobby, but mostly scared for me. If I go back to school, I will get too scared to pay attention to my teacher. I might pass out, or I might throw up, which is the worst thing that could ever happen. I can’t go back to school, and I’m sad that I’m scared.”

A: Access

There are a few parts to the access step. Once children have identified the problem, we first suss out the different parts of themselves that are emerging. In Esme’s story, part of her was sad for Bobby, another part was afraid she might get sick, another part was scared to go to school, and yet another part was sad that she was feeling scared. The next step is to determine whether these parts overlap or they feel distinct.

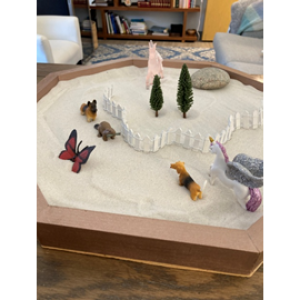

With children, you can assess this by asking them to draw each part on a piece of paper or to use a therapeutic sand tray. We used the sand tray to do this exercise with Esme.

Sand tray therapy is a form of therapy that allows individuals to externalize thoughts, images, parts, or feelings through representation of different figures selected and placed in the sand tray.8 Analysis may be of the figures and/or their placement relative to other variables in and around the tray.

Figures 1a and 1b depict 2 pictures of the sand tray that Esme created.

Figures 1a, 1b. Esme’s Sand Tray

Here are some highlights from Esme’s description of the sand tray:

- The pink unicorn was Esme’s healthy happy self. It was being protected by trees and a fence.

- Bobby was the puppy with his tongue out, representing him being sick

- The pegasus to the right represented how happy Esme used to feel when she went to school. Interestingly, she placed the pegasus slightly behind the dog/Bobby at the edge of the sand tray.

- Esme said that the dog to the left in this image was her sad self, with his tail down, looking at school from afar

- When I asked Esme who the beaver was, she said that the beaver was protecting the dog from Bobby

We have accessed the problem and identified the different parts that came up. The next step is to identify which part the child wants to work on first.

Esme decided she wanted to work on the part that was scared of getting sick, which she said was represented by the beaver.

At the beginning of our conversation, Esme was unsure who the butterfly represented. She thought the butterfly was pretty, like a guardian angel. We discovered more later.

The next part of the access step involves zooming in on the part we want to work with. In this step, we ask the child what thoughts, feelings, and sensations come up as he or she thinks about that part. Whatever comes up is relevant.

As you will see in the next example, when Esme did her 4-part P.A.R.T. exercise, she was initially able to dial in on what she was feeling logically; however, when it came to noticing her body, her brain kept getting distracted.

We eventually discovered that distraction and imagination are tools that Esme’s brain uses when she is extremely upset. This is commonly seen in children who dissociate or detach from their mind or surroundings during high-stress times. By exploring this together, Esme was ultimately able to recognize her distractibility before it gained momentum.

Here is her description: “The beaver feels nervousness in her tummy. It’s rumbling and moving all around.” [Esme sighs.] “I think I’ll draw a picture for my best friend. She has a pet guinea pig, and I can draw that for her. Did you know that guinea pigs eat lettuce and when you open the refrigerator, they recognize the sound and squeak a lot?”

R: Retrieve the Memories

The key objective of this step is to identify the early memories with which this feeling is associated. It helps to focus on the root cause. Think of it as a ball of yarn: Once you find the strand sticking out, you can follow it into the middle, untangling the web as you go. For children who are older and able to write, you might ask them to write the “prologue” as a part of untangling their story. Storytelling is another strategy for creatively exploring deeper feelings and associations.

Here are some questions to ask:

- What is this figure thinking/worried about?

- When you think about this issue/pain/emotion, what kind of thoughts and memories come up?

- When did this issue begin?

- What was going on in your life when this all started?

Esme had a fairly big realization during this part of the exercise: “I used to love school, especially voice class. When I am sad or worried, the teacher plays the piano and we sing songs, and it’s like all of the bad feelings fly away. Oh!” Esme stopped mid-sentence. “Like the butterfly!” She pointed at the butterfly on the sand tray. “She carries me away and I’m happy!”

But when Bobby got sick, the butterfly couldn’t carry Esme away. The teacher stopped playing, and the music ended, and Bobby was still sick. Suddenly Esme’s sanctuary from stress and worry had been tainted by a scary and negative experience, causing Esme to feel out of control and afraid.

T: Tend to the Triggered Part

Sometimes it helps to name the part: This is my “scared part,” my “resentful part,” the “warrior part,” the “11-year-old part,” the “antagonist part,” etc. Once we have identified what part of the person is suffering and how that part is expressing its suffering, we have to ask permission to work with that part, to meet its needs and promote healing. In Esme’s story, you will see the metaphors between what the beaver figure needs and what Esme has been seeking to achieve on her own. By meeting that need internally, the pressure to use external means to protect herself will be reduced.

Dr Cain: Tell me about the beaver.

Esme: This beaver is afraid of getting sick, and she puts her tail flat on the ground and is holding onto sticks for her house. She is protecting the dog, who wants to go to school, but dogs can make each other sick. That happened to my dog one time. We had to board her while we went on vacation, and she got a cough.

Dr Cain: That beaver is very brave for protecting the dog and herself. What do you think the beaver needs in order to feel more safe?

Esme: She needs a house around her to protect her.

Dr Cain: That makes sense. What if we were to build her that house?

Esme: She’d like that.

Dr Cain: Let’s imagine doing that now. You can build it with anything you’d like. What shall we build with?

Esme: Glitter.

Dr Cain: Perfect. So let’s look at the beaver, and imagine we are building a protective bubble around her made of glitter. This glitter will keep her safe, so even if Bobby, the dog, gets sick, she will be healthy and protected.

By helping children to acknowledge and tend to their different parts, they learn the process of holistic integration. This is a process of bringing together the different elements of the mind, body, and spirit. Through integration, children are able to employ perspectives, skills, needs, and resources from different parts of their development.9 Integration is a part of psychological maturation, and integrated individuals are less likely to reject parts of themselves or struggle with internal conflict, and are more able to manage and process emotions and symptoms.

Social Characters

We are intimately impacted by those who surround us. This includes family, friends, and our communities.

Social Psychology is a branch of psychology that examines the impact of interactions (or a lack thereof) between groups and individuals on a person’s psychology or well-being.10 Studies in social psychology have demonstrated how children’s behavior is impacted by their social surroundings and how they “mimic” the “behavioral modeling” with which they had been primed.11 Additionally, and unsurprisingly, research into the effects of COVID-19 quarantine and social isolation has revealed that social isolation is associated with increased levels of depression and anxiety in children.12

Social Psychology believes that if you are surrounded by people who are anxious, you are more likely to be anxious yourself. If the people in your life constantly tear you down, your psyche will likely do the same to you. In contrasting, if the people you surround yourself with are confident and build each other up, you will likely feel more confident and build yourself up more.

When it comes to the social cast of characters in our children’s emotional well-being, 6 key social factors should be considered:

- Peer relationships

- Adult relationships

- Household dynamic

- Political climate

- Socioeconomic status

- Culture (home and community)

Let’s explore each of these in more detail. I have provided you examples of questions to include in your assessment; however, this is not intended to be a complete list.

Peer Relationships

Peer relationships are among the most important social variables in childhood, and particularly for adolescent well-being.13 As such, a thorough exploration of peer relationships is prudent whenever exploring the root causes of both mental and physical symptoms.

Questions to consider as they pertain to anxiety, in particular:

- Is the child exposed to peers on a regular basis?

- What are the child’s peers like? (eg, their personal well-being and home life)

- What is the quality of the child’s peer relationships?

- How does the child relate to peers?

- Does the child report any feelings of loneliness?

- Is there any evidence of current or past bullying?

- Has the child learned about personal boundaries, and does the child feel respected in his or her boundaries?

Adult Relationships

Oftentimes, a child’s mental health is a reflection of their primary adult relationships. The job of the adult caretaker is, in part, to attune to the needs of the child. If there is a gap between the child’s needs and their adult caretaker’s ability to respond, the child may suffer from both emotional and physical symptoms that can extend well into adulthood. In addition to the primary adult caretakers, other adult mentors and role models may positively or negatively impact a child’s mental health.

Questions to consider regarding the adults in a child’s life:

- Who are the adults that the child is exposed to?

- What is the nature and type of relationship the child has with these adults?

- Are the adults experiencing any mental or physical symptoms of their own?

- How is the child expected to respond to stressors?

- Does the child go to a babysitter or childcare center?

Household Dynamic

Similar to the topic of adult relationships in exploring the nature of childhood anxiety, it is important to assess the child’s household dynamic.

Questions to ask to screen for variables:

- Is the child’s housing stable?

- Is the house clean or messy?

- Does the child have his or her own private or designated space?

- What is the child’s role in the family?

- Do the residents of the house change frequently?

- Do strangers come and go from the house?

Political Climate

Around 2 years of age, children begin to develop empathy for others.14 While they may not clearly understand what is going on in the news, on the television, or on the radio, or what is being said at the dinner table, children notice and often take in the emotions of those around them. As such, during times of political discord or unrest, children can be affected.15

Questions to ask:

- Is there a current political event (worldwide, national, or local) that the child is aware of or being impacted by?

- Is the child exposed to news outlets, the media, or conversations about political events?

- Is the information disclosed in an age-appropriate manner?16

- How are the people around the child emotionally dealing with the political climate?

- Is the child or family’s perspective in alignment with the larger local community?

Socioeconomic Status

Financial stress not only impacts the child’s caretakers, and thus the child indirectly, but also impacts children directly. The effects range from decreased attention and focus and increased depression and anxiety in childhood, to longstanding physical and emotional health issues later in life.17 When considering the root cause of anxiety, going beyond the biomedical perspective opens the doors to helping children turn the page in their story of anxiety.

Questions to consider when assessing socioeconomic stress:

- What is the financial status of the child’s caregivers?

- Does the child suffer from inadequate housing, food, clothing, or other necessary resources?

- Is the child’s caretaker anxious about finances?

- Have there been any major changes in the child’s socioeconomic status?

Culture (Home & Community)

When we think about culture, what might initially come to mind are religion, politics, and family traditions. Culture is an important part of the foundation of human psychology, and our culture informs the development of our mental and emotional experience from the very first moments of conception. Culture Psychology is a branch of psychology that emphasizes the relationship between culture, psychology, and concepts related to morality, identity, gender roles, sexuality, and religion.18 Exploring culture can provide clues as to risk factors and protective factors in a child’s emotional well-being.

Questions to consider:

- What are the child’s family’s cultural or religious beliefs regarding mental and physical illness?

- What are the child’s family’s cultural or religious beliefs regarding treatment of mental and physical illness?

- Does the child feel safe in the neighborhood in which he or she lives?

- What is the quality of community resources?

- Is the community supportive of the child and their family with respect to their needs and preferences?

Physical Characters

Physical Characters, which may also be referred to as our biological characters, refers to the interrelationship between our mental and emotional health and physical factors, such as genetics, hormones, neurotransmitters, and gut and endocrine health.

The primary objective of this section is to provide age-appropriate education to children regarding what happens in their bodies when they become anxious and what they can do to feel better.

The first step is to understand what is happening when children feel anxious. There are many wonderful online videos that explain anxiety. For example, Anxiety Canada’s YouTube Channel19 has videos on mental health for kids in different age groups. My favorite video explaining the fear response in a child is Anxiety Canada’s video, “Fight Flight Freeze – A Guide to Anxiety for Kids.”20

The second step is to provide tools that children can use right away when anxiety strikes. This involves first helping them learn how to make their own “Panic Pack,”21 and then supporting them in learning how to identify when and how to use the Panic Pack to self-regulate. Because there is down-regulation of the prefrontal cortex and upregulation of the emotional brain during a panic attack, strategies that target the brainstem tend to be more effective for de-escalation.

The Panic Pack and the 4-S Model are designed to teach children strategies for soothing their anxiety by tending to the brainstem.

The 4-S Model

- Scene

- Scent

- Sip

- Stimuli

#1: Scene

Your scene is filled with specific types of lighting, sounds, smells, textures, and other stimuli.

The brain is associative. So, if you are in a triggering environment, changing it up may throw a wrench into the bicycle spoke of panic.

When I was dealing with extreme anxiety, I found that being in my apartment made it worse. And so I would leave and go to parks, or visit my friends and hang out in their houses. Changing the scene will help your brain let go of associations that may be feeding into your current state.

Here are some scene-shifting-suggestions:

- Physically relocate yourself. If you are inside, go outside, and vice versa. If you’re in your office, get up and go to the bathroom.

- If you’re in a dark room, go into a light room, and vice versa

- Go for a run, walk, or bike ride, or jump on your longboard

- Change your bedspread or rearrange your furniture. Move the things on your desk.

#2: Scent

Using scents can be a powerful cue for the brainstem, and scents can invigorate or calm. Make sure your environment is clean, smells fresh, and is clutter-free.

Here are some super-smelling scent suggestions:

- Inhale essential oils. You can use a diffuser, a candle, or whatever you like. Some of my favorite scents for anti-anxiety are: citrus (especially lemon), lavender, chamomilla, vetiver, rose, or ylang ylang.

- Apply essential oils to the insides of your wrists, on the bottom of your big toes, at your temples, or beneath your nose on your upper lip

- Smell a perfume or a candle scent that you love

#3: Sip

Sipping relaxing teas (iced or hot) or taking calming amino acids and herbs can help relax a nervous system that’s on overdrive.

Sipping also allows you to notice taste, texture, and temperature on your tongue and in your mouth.

Try chewing ice or drinking hot tea. Here are some of my favorite tea-boosters that you can ask your doctor about:

- Ingredients from my own GABA-stimulating formula (theanine, taurine, inositol, glycine, and phosphatidylserine) can all be added to tea or water

- Herbal teas containing kava kava root, lavender flower, passiflora flower, chamomilla flower, lemon balm leaves, and/or dried oat tops.

#4: Stimuli

Distract yourself from an emotional event by stimulating your nervous system in other ways.

Remember that the stimuli should be as strong, or stronger, than the intensity of the feeling of anxiety. This means that if your anxiety is low, gentle changes in your environment may be sufficient. However, if your anxiety has shifted into panic, you will likely need a more intense stimulus.

To change the stimuli, experiment with different options, listening to your body’s feedback and making notes for your future self.

Here are some ideas:

- Change your body temperature, otherwise referred to as “tipping the body temperature,” a concept taught in Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT).22 This is a way to change the stimuli going into your body. Try taking a super-hot shower. Or put on a heated vest, heated blanket, or weighted blanket, jump in a cold pool, alternate hot and cold in the shower (hot for 1 minute, cold for 15 seconds, repeat several times), open the windows if they are closed, or change the temperature in your home.

- If it is dark where you are, try flipping on all the lights, or vice versa. Increase or decrease the wattage, try a different color, or use a full-spectrum light.

- If it is quiet where you are, try turning on music, including relaxing music or something with a heavy beat. Or maybe turn on a white-noise machine or humidifier, or play music or a podcast in the background.

- Change your shoes, change your socks, or put on a different shirt. If you’re wearing a hat, take it off. If you’re wearing glasses, maybe put in contacts.

- If the music is on, change the station, style of music, or volume, or maybe even turn it off. If it is quiet in the room, experiment with different types of sounds. Download a white-noise app into your phone, and try listening to ocean waves, thunder, rain, train tracks, or fans. Listen to the feedback from your body and make notes.

- Distract your brain by watching a funny movie or your favorite comedy

- Focusing outward is profoundly important. If you’re feeling stuck in a rut, consider getting out and volunteering. Spend time out with a friend or loved one.

Conclusion

Through examination of Esme’s Cast of Characters, we were able to identify several key root-cause factors contributing to Esme’s symptoms of anxiety, and treatment was tailored to include her autonomous needs, creativity, and imagination.

The research has been very clear that there is a link between a child’s well-being and the components described by the Cast of Characters. Armed with a foundation of knowledge in the Cast of Characters and naturopathic modalities, the clinician’s diagnostic lens widens, and the repertoire for individualization of care expands exponentially.

The child’s body is wise, and if we pay careful attention to its messages, we can learn how to identify solutions that not only relieve suffering in the moment, but also plant the seeds for a more emotionally healthy and vibrant life.

References

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136.

- Narmandakh A, Roest AM, de Jonge P, et al. Psychosocial and biological risk factors of anxiety disorders in adolescents: a TRAILS report. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020 Oct 28. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01669-3. [Epub ahead of print.]

- Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, et al. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:449-461.

- Stanborough RJ. Concrete Thinking: Building Block, Stumbling Block, or Both? August 30, 2019. Healthline. Available at: https://www.healthline.com/health/concrete-thinking. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- Shapiro R. Easy ego state interventions: Strategies for working with parts. New York, NY: W W Norton & Co; 2016. Available at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2016-00519-000. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- The Internal Family Systems Institute. The Internal Family Systems Model Outline. 2021. IFS Institute Web site. https://ifs-institute.com/resources/articles/internal-family-systems-model-outline. Accessed June 11, 2021.

- EMDR International Association. Integrating EMDR, Structural Dissociation, Attachment Repair & IFS Parts Work. May 1, 2020. EMDRIA Web site. https://www.emdria.org/event/integrating-emdr-structural-dissociation-attachment-repair-ifs-parts-work-may-2020-philadelphia/. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- Texas State University. The Institute for Play Therapy. Sandtray Therapy Certification. 2021. Available at: https://playtherapy.clas.txstate.edu/sandtray.html. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- Good Therapy. Integration. Last updated August 10, 2015. Available at: https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/psychpedia/integration. Accessed June 14, 2021.

- Mitchell JP. Social psychology as a natural kind. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(6):246-251.

- Mcleod S. Bobo Doll Experiment. Updated 2014. Simply Psychology. Available at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/bobo-doll.html. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218-1239.e3.

- Pickering L, Hadwin JA, Kovshoff H. The Role of Peers in the Development of Social Anxiety in Adolescent Girls: A Systematic Review. Adolescent Res Rev. 2020;5:341-362. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00117-x. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- Abedon EP. Toddler Empathy. October 3, 2005. Parents. Available at: https://www.parents.com/toddlers-preschoolers/development/behavioral/toddler-empathy/. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- Guidance Resources. Civil Unrest Resources. 2020. Available at: http://wellness.uci.edu/programs/eapmaterials/CivilUnrest.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- Knorr C. Explaining the News to Our Kids. Common Sense Media. Available at: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/blog/explaining-the-news-to-our-kids. Accessed June 7, 2021.

- Morrissey K, Kinderman P. The impact of financial hardship in childhood on depression and anxiety in adult life: Testing the accumulation, critical period and social mobility hypotheses. SSM Popul Health. 2020;11:100592.

- Biswas-Diener R, Thin N, Sanders L. Chapter 15.1 Culture. In: Cummings JA, Sanders L, eds. Introduction to Psychology. Saskatoon, SK: University of Saskatchewan Open Press; 2019. Available at: https://openpress.usask.ca/introductiontopsychology/chapter/culture/. Accessed June 11, 2021.

- Anxiety Canada. Mindshift CBT. [YouTube video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCdaieRTcpBA7wygZEcwakWw. Accessed June 11, 2021.

- Anxiety Canada. Fight Flight Freeze – A Guide to Anxiety for Kids. [YouTube video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FfSbWc3O_5M. Accessed June 11, 2021.

- Cain N. Learn how to Make Your Own Panic Pack today. June 12, 2020. [YouTube video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3F4YpWFczJI.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy. T10: TIPP. Available at: https://dialecticalbehaviortherapy.com/distress-tolerance/tipp/. Accessed June 20, 2021.

Nicole Cain, ND, MA has been interviewed as a mental health expert in Forbes, has published in journals such as NDNR, has been a national speaker for PESI, and is the founder and creator of the internationally recognized Anxiety Breakthrough Program. She has a master’s degree in clinical psychology with a specialization in counseling, as well as a Doctorate of Naturopathic Medicine. Dr. Cain can be found on Instagram @DrNicoleCain.