Nature Cure Clinical Pearls: The Half Bath

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

From long experience, the shorter the time the better; and that it is wiser to take two short baths than one long one.

Sebastian Kneipp, 1901, p.14

How long should be the duration of the Half Bath? Two to three seconds are sufficient: just long enough to count one, two, three.

Benedict Lust, 1901, p.296

Whatever the acute conditions may be – a simple cold, measles, typhoid fever or smallpox – the following treatments applied singly, combined or alternating, in accordance with individual conditions, will always be in order. The Cold Bath.

Benedict Lust, 1910, p.85

The bathtub and the fine ritual of bathing seem to have slipped into nostalgia – old habits of grandparents and ancestors. Even so, bathtubs are still common features in North American bathrooms, whether in residencies or hotels; yet their use has declined so significantly that bathtubs are either attractive drainage basins for showers or consigned to a mere ornamental feature in a modern home. The switch to showering as the dominant means of personal hygiene renders the unused bathtub as the proverbial white elephant, sometimes occupying coveted space in our small bathrooms.

Why the shift in our personal bathing choices? Perhaps our lives are so hectic and busy that taking a 20-minute bath feels like we are squeezing the impossible into our days. There is, of course, the rationale that showering is simply more hygienic and uses less fresh water. But, oh, have you had a bath lately? Time slows when bathing, and whatever worries or burdens that may have been brooding in the back of our minds seem to dissolve somewhat, and even to transform, during the bath. When the bath is finished, we are squeaky-clean and ready to tackle our next endeavor.

Reclining in a bathtub, leisurely pondering our day, was not the type of bathing, though, that the early Naturopaths counseled their patients to take. Undeniably, water was considered the ultimate solvent to cleanse the body; however, water used therapeutically in the form of the bath proved to be a valuable part of improving and maintaining one’s health. Let’s rekindle our curiosity for what our forebears called the Half Bath.

The Half Bath was used by several hydrotherapists in the early 20th century; however, the influence of Sebastian Kneipp was instrumental and pervasive in the application of this bath. Kneipp, it is useful to note, was not the originator of the Half Bath, according to John Harvey Kellogg: “The term Half Bath devised by Priessnitz, is really a misnomer, as in this procedure the application involves the whole surface of the body.” (Kellogg, 1903, p.596) Ever the teacher, Kneipp provided to Benedict Lust and his fellow Naturopaths clear instructions, which were made available in Lust’s English version of The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly [1900-1901]. Lust employed these Half Baths himself, and wrote articles in his early publications to help guide his colleagues. Lust also reprinted articles from Sebastian Kneipp, to add to the available information. Bathing was soon a key element in the early Naturopath’s armamentarium, and the Half Bath itself provided a therapy that was effective and reliable.

The inclination to bathe in warm water did not resonate with the early Naturopaths. It is important to keep in mind Hartmann’s dictum: “Warm baths only appeal to the senses, but they never cure any ailments, because warm water has not the least power of resistance.” (Hartmann, 1905, p.246) The Half Bath, as one might expect, used cold water at tap temperatures and was conducted in ordinary bathtubs (Figure 1). Never did the early Naturopaths condone the use of ice or ice water in their hydrotherapy. (Lust, 1910, p.85)

Figure 1. The Half Bath

The Half Bath involved getting the lower part of the body wet. Not only was cold tap water an essential aspect of the Half Bath; so too was the duration of time spent in the bathtub. That time frame was exceedingly short. Kneipp elucidates the rationale for a short bath: “Formerly, as stated in My Water Cure, I ordered [the Half Bath] to be taken from one and half to three minutes; now I never permit it longer than from two to six seconds.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.14) Kneipp explains, “My reason for shortening the time is that patients taking the Half Bath have as a rule two other water applications in the day, besides wading in water.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.14)

Sitting or standing in cold water, alas, can inhibit people from trying some of the Kneipp cold-water therapies, even when the benefits are so great. In this regard, the volume of water that the patient is exposed to in a Half Bath mitigated the aversion that cold water instilled. Because the volume of water was less, the perception was more receptive for half baths. Kneipp’s patients favored the Half Bath for this reason. The patient’s upper body could remain dry or only gently splashed with water. (Kneipp, 1901, p.14)

The Half Bath

As we have seen, then, the Half Bath according to Lust was a very short bath. His instructions were as brief as the experience: “Go into the water up to under your arms, count one, two, three and go out.” (Lust, 1900, p.103) The short duration of the Half Bath is justified. The temperature of the water is cold and not the type of bath where one lounges in the bathtub. Lust advises his readers, “A Half Bath should not be lukewarm, because it would then not be of any material advantage.” (Lust, 1901, p.296) On the other hand, there were hydrotherapists such as Curan Pope who established water temperatures between 75° to 65° F/24° to 18° C as standards for the Half Bath. To help patients adjust to the cold, Pope advised, “Always commence with 85° F/29° C or even 90° F /32° C and reduce the temperature two or three degrees daily until the desired point is reached.” (Pope, 1909, p.147) Pope also conducted Half Baths in clinical settings where a bath attendant would fulfill the delivery of ablution and friction rubbing that was prescribed during the bath. By using warmer temperatures than advocated by Kneipp and his followers, Pope also administered longer baths. He states, “The duration of the [Half] bath should range from two to five minutes, at the end of which time the patient receives an affusion, over the back and shoulders, of water several degrees colder than that in the tub.” (Pope, 1909, p.148) The affusion that Pope references is simply the pouring of water from a vessel onto the patient. In some ways, Kneipp and Pope are achieving similar outcomes: a short exposure to cold water.

The Half Bath could be taken in 3 positions: standing, sitting, or kneeling. If standing, the amount of water in the bathtub “reaches above the calves or above the knees.” (Lust, 1902, p.413) If the sitting position is used, “the water reaches to about the navel, [and] to kneel in the water so that the whole of the thighs is covered.” (Lust, 1902, p.413) For those taking Half Baths, the recommended procedure included splashing water on the upper body, not so much as to provide a thorough cleaning, but to harden the body with additional cold water. In this connection, Lust recounts his experiences in the European spas including, Kneipp’s Wőrishenofen: “In all water cure institutes the patient always receives a gush of cold water upon his back additionally after each [Half Bath].” (Lust, 1901, p.296)

The Half Bath is quite similar to Adolf Just’s Natural Bath in that each bath requires very little water and is very short in duration. Just explains the Natural Bath: “The bather sits down in the bath tub which contains naturally cold water, about three and half inches (8 cm.) deep, so that the seat, the feet, and sexual organs are for the most part in the water… Water is vigorously dashed over the abdomen with the hollow of the hand… followed by a brisk rubbing of the abdomen… with one or both hands.” (Just, 1901, p.266) However, Just’s Natural Bath emphasized friction and rubbing of the abdomen and pelvis, whereas the Half Bath involved “rapidly wash[ing] the upper body superficially and throw[ing] a few handfuls of cold water over shoulders and back.” (Lust, 1901, p.296)

Figure 2. Bath Cabinets

No Towels Needed

The early Naturopaths did not stop there. They referenced, as well, the very means that we habitually use after a shower or bath as being the worst of the worst options. What I am referencing here is the common towel. Kneipp abhorred the use of the towel for the purpose of drying after water applications. Many of the rules established by Kneipp for water therapy also applied to the Half Bath. There are many Naturopaths who contend that one of Kneipp’s greatest contributions to hydrotherapy was his banishment of the use of towels. Lust remarks, “This not drying the body is the one process by which Kneipp got his greatest and best results, for this places the patient in such a state of satisfied rest, as cannot be imagined, and which must be felt and passed through by oneself to understand how beneficial it acts upon the nervous system.” (Lust, 1901, p.56) Kneipp established a stringent rule that after water applications, one either dressed immediately into clothing, or [went] to bed without ever drying his or her wet body. “The body should not be rubbed dry with a towel, but should be left to dry of itself.” (Lust, 1900, p.103) Some suggestions in place of the towel included the following: “The best plan is to cover up tight between blankets for a few minutes, the next best to don underclothing and exercise vigorously, the next to dry by hand-rub and evaporation, [and] the least salutary is wiping dry and rubbing red.” (Lust, 1904, p.4)

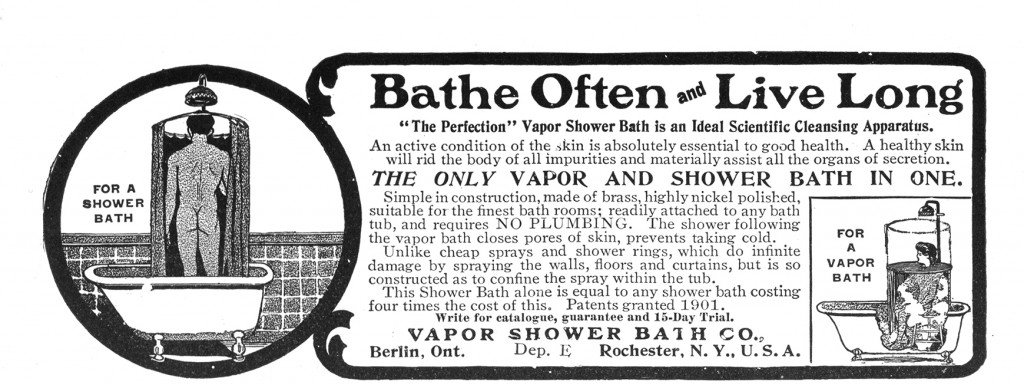

Kneipp maintained that a cold water application was sufficient to warm up the body by increasing circulation. Not drying oneself mimicked a steam bath. Lust explains, “Kneipp’s process of ‘not drying the body’ produces, with the help of the adhering water, its own steam bath, which certainly is the most natural form of a steam application.” (Lust, 1901, p.57)

Figure 3. The Vapor Shower Bath

Exercise, Exercise!

One of the most important elements of cold water bathing is that the patient must be warm beforehand. Lust states the most crucial rule: “Cold water should never touch cold flesh.” (Lust, 1904, p.4) To warm the patient, many options were available for the early Naturopath: firstly, exercise; then massage, followed by warm applications. Rev T. Hartmann, an avid follower of the Kneipp method, remarks, “Children are told not to go into the water if their bodies are in full sweat; but I can assure everybody that the warmer the body, the more powerful the bath.” (Hartmann, 1905, p.248) Lust was in full agreement with Hartmann: “The body should be thoroughly warm; the warmer the better and the more agreeable and more salutary will the Half Bath prove to be.” (Lust, 1901, p.296) The Half Bath, like the other hydrotherapies established by Vincent Priessnitz and Sebastian Kneipp, consistently relied upon exercise to ensure warmth. Kneipp was strict regarding exercise, especially after the Half Bath. Indeed, the following passage from the esteemed priest demonstrates how clear his language was in this matter: “The baths must be taken while the patient is quite warm and exercise must follow immediately after to promote a full natural warmth.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.14) Even so, there are some who are stimulated by a cold bath and generate lots of body warmth, who may think that exercise is not necessary; once again, though, Kneipp stresses the importance of exercise after the Half Bath. “Many who are tolerably warm after coming out of the Half Bath think exercise can be dispensed with. This is wrong; the warmth they experience is the first reaction, and others will follow. Exercise must be taken to prevent the entrance of cold.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.14) For those unable to exercise, another option was available, ie, to rest in a warm bed.

The Virtues & Benefits

“These Half Baths should be taken right after rising in the morning or at any convenient time during the day, but never before two hours have passed after a meal.” (Lust, 1900, p.103) The Half Bath was also used in the middle of the night, much like the neutral bath, to help patients sleep. One caveat appears in the literature, however, and is focused on nervous and anemic people; it was that the Half Bath was not advised “before going to bed for the night, because it excites them. But after a rest of a few hours, when the body has been strengthened and the nerves quieted, the Half Bath will certainly prove beneficial.” (Lust, 1901, p.297)

While the early Naturopaths and Kneippians refer to the main value of the Half Bath as hardening the body, Pope and John Harvey Kellogg offer more tangible and scientific merits in their writings. Lust sums up the benefits: “The Half Bath strengthens the body and hardens the constitution and may be taken by all sick as well as healthy people. For the latter, a bi-weekly Half Bath is quite sufficient. As it greatly strengthens the abdomen, it is especially recommended [for women].” (Lust, 1901, p.297) In an earlier issue of The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, Lust recommends the Half Bath for mothers, to strengthen their bodies and “keep the blood in proper circulation and produce the necessary natural temperature of the body.” (Lust, 1900, p.103) In its various forms, the early Naturopaths felt that the Half Bath benefitted the whole body. (Hartmann, 1905, p.149)

Kellogg summarizes the physiological effects of the Half Bath: “It combines the effects of the rubbing wet sheet, the affusion, and the immersion bath, producing powerfully alterative and tonic effects by reasons of the repeated and ever-varying thermic and mechanical impressions made upon the skin.” (Kellogg, 1903, p.596) While the early Naturopaths refer to the virtues of hardening, the hydrotherapists suggested, “the power to increase vital resistance is clearly indicated by its effect in increasing muscular capacity.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.597) Whether the patient was sick or desiring to be healthier, the Half Bath was always taken with other hydrotherapies. There were many to choose from, such as water treading, gushes, compresses, etc. This bath’s brevity of a couple of seconds’ duration helped patient compliance. However, for those who suffered with serious ailments, such as typhus or abdominal complaints, the sitting Half Bath was unrivaled as a treatment for those weakened and despaired by diseases. Kellogg used the Half Bath to treat a wide range of ailments, spanning from cardiac ailments, asthma, spinal disorders, chronic myelitis, and meningitis, to ataxia with paralysis. (Kellogg, 1903, p.597) He also recommended the Half Bath for “neurasthenia, hypopepsia, chronic constipation, diabetes, uric acid diathesis and a large class of disorders due to uric acid accumulation.” (Kellogg, 1903, p.598) Uric acid excess is currently once again gaining attention in medical circles as a trigger for inflammation, and contemporary naturopathic physicians would do well to follow Kellogg’s protocols for such patients.

The power and strength of the Half Bath was its ability to strengthen a person’s constitution by hardening those who dared to try this amazing “count to 3!” bath. Never underestimate the power of this 3-second bath. Rev T. Hartmann witnessed the following: “When water is applied to a sick body in the right manner, it will gradually act upon all diseased portions; it will search for the diseased matter, and dissolve and expel it so that one will gradually feel quite comfortable.” (Hartmann, 1905, p.147) There were definite rules and guidelines for the practice of hydrotherapy. The early Naturopaths have left us with a rich compendium of advice, protocols, guidelines, and suggestions to use water in our healing practice. The Half Bath is one of the abundant tools which we have available from the past; it is as powerful today as a century ago in helping patients recover and enjoy health.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

References

Hartmann, T. (1905). On the water cure in general. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VI (6), 147-149.

Hartmann, T. (1905). On the water cure in general [continuation]. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VI (6), 246-249.

Just, A. Return to nature. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (10), 264-267.

Kellogg, J. H. (1902). Rational Hydrotherapy. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company Publishers, pp. 1193.

Kneipp, S. (1901). The half bath. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (1), 14-15.

Lust, B. (1900). Applications of water for mothers. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (6), 103.

Lust, B. (1901). The half bath. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (11), 296-297.

Lust, B. (1901). The process of not drying oneself, according to the Kneipp water treatment. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (2), 56-57.

Lust, B. (1902). The Kneipp cure. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, III (10), 413-414.

Lust, B. (1904). Health incarnate. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, V (1), 4-7.

Lust, B. (1910). The treatment of acute disease. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XV (2), 85-86.